The more things change, the more they stay the same. The old wild men were more uncanny and unpredictable than they were given credit for. The old order was not that orderly after all. There is no such thing as a complete rupture in art and that negation and nihilism must eventually wither and become obsolete or transform itself. Theory and politics in Meyer Schapiro, a voice of the American left was that the Middle Ages saw much escape through the cracks in its foundation, a foundation built on order, rank and definition that was also questioning its sometimes own shaky assumptions. This mutational aspect always fascinated Schapiro; the porous boundaries, the “in-between” of divine ordinance, the fascination with the mutually contradictory led him to assert that no quality or trait in art exists without its contrary.

---On the aesthetic attitude in romanesque art; From mozarabic to romanesque in Silos; Romanesque sculpture of Moissac I & II; On geometrical schematism in romanesque art; ---Read More:http://www.medievalbookshop.co.uk/aiitems/AIF0053.shtml

( see link at end)…The leading American medievalists at Harvard and Princeton saw it as their duty to erect a barrier against the tide of materialist mass society and the large immigrant population that, they felt, threatened to swamp the old cultivated classes of the eastern seaboard. In their minds, to contemplate and comprehend the art of the Middle Ages was imaginatively to reenter a society of order, rank, and deference. To imagine an art history with different aims than this, Schapiro, as a son of Jewish immigrant parents, had to imagine a different Middle Ages. And by the time he submitted his Moissac dissertation to Columbia, in 1929, he was losing his confidence that he had succeeded. In particular, time spent living among the monks of Silos, one of the great Romanesque monasteries of northern Spain, convinced him that art history was hobbled by its failure to theorize the relations between visual form and the complex of social interests within which it was embedded. Read More:http://l-young.tistory.com/161

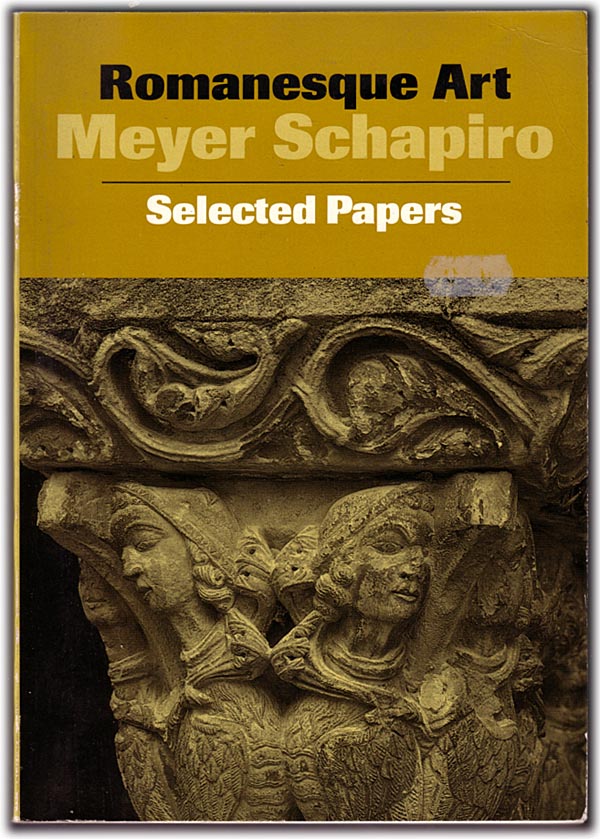

---Indeed, the medieval vision of life on earth, the promises of heaven and the horrors of hell, may be followed closely through this profusion of carved stone. In his brilliant essay on the Moissac sculpture, Meyer Schapiro leads the reader on a visual tour of the abbey. Through his penetrating descriptions and analyses of the various figures, we can come to an understanding of the aesthetic and philosophical bases not only of this ensemble, but of all Romanesque art.--- Read More:http://www.en.zvab.com/basicSearch.do?anyWords=Schapiro+Romanesque+Art&ts=schapiro-romanesque-art

…The freedom of the Modern artist was, he made plain, as qualified by circumstances as that of the medieval artist had been. And that perception proved to be double-edged, in that to speak at all of degrees of freedom had just as transforming an effect on the blinkered assumptions then reigning in medieval art history.

The prevailing account of Romanesque style had assumed a social order that held the individual in a position determined by birth and prescribed by divine ordinance; the medieval sculptor was assumed to be bound by the requirements of a dogmatic theology handed down from above, from which no deviation was permitted.” But this account was one that a single powerful exception would falsify, and Schapiro found two in Souillac and Silos. The innovative moments in the art of both complexes were bound up with rendering sin and disbelief in the most compelling possible form: here dogma was no guide, so artists, whether monks or lay artisans, had to accommodate emerging secular interests, even dissent against ecclesiastical authority. Far from being obedient to rigidly symmetrical formats, Romanesque artists could create “discoordinate” compositions of fiendish complexity, achieving visual order of a higher level out of intimations of pervasive flux and instability in human existence. ( ibid. )

ADDENDUM:

Written at a time when art historians were mainly preoccupied with difficulties of attribution, patterns of stylistic development and questions of imagery (iconography), these essays struggled with the ways in which social and political conditions affect or limit artistic production and artistic form. For example, in the essay on Silos, published in 1939, Schapiro attempted a comprehensive sociological explanation of romanesque style, arguing that any renewed study of the subject would require “the critical correlation of the forms and meanings in the images with historical conditions of the same period and region.” Read More:http://www.solidarity-us.org/node/2424

————————

Fifty years earlier, in the Romanesque church at Souillac, a surprisingly different approach to the akedah is taken. In 1939, world-renowned art historian Meyer Schapiro argued that the sculptures in this 12th century church reveal reservations about church doctrine regarding submission and dominance.

“It should be observed … that the theme of Abraham and Isaac, which is not only a symbol of salvation

of the Crucifixion but also…of submission to authority… is parodied on the opposite side of the trumeau by images of conflict between a youth and an old man, wrestling pairs who resemble Abraham and Isaac.” Read More:http://www.tali-virtualmidrash.org.il/ArticleEng.aspx?art=6

COMMENTS

COMMENTS