A part of the charge of immaturity often brought against J.D. Salinger is the fact that he did not deal with mature love. The implication is that he “escapes” from sex. It is an open question whether this escape is not one of the things that makes him so popular. The accepted formula for success in his time, and our for the most part, is an abundance of sex, but it is entirely possible that a point of surfeit had been reached. “Mature Love” between men and women has not always been at the center of the storytelling art. The great epics dealt more with the themes of war, nature, and the gods. It is hard to imagine a novel without a love story; but mature love alone has rarely been sufficient to sustain fiction, and it has always needed the admixture of the other, older themes. It is just possible that Salinger’s sexless story came as something of a relief.

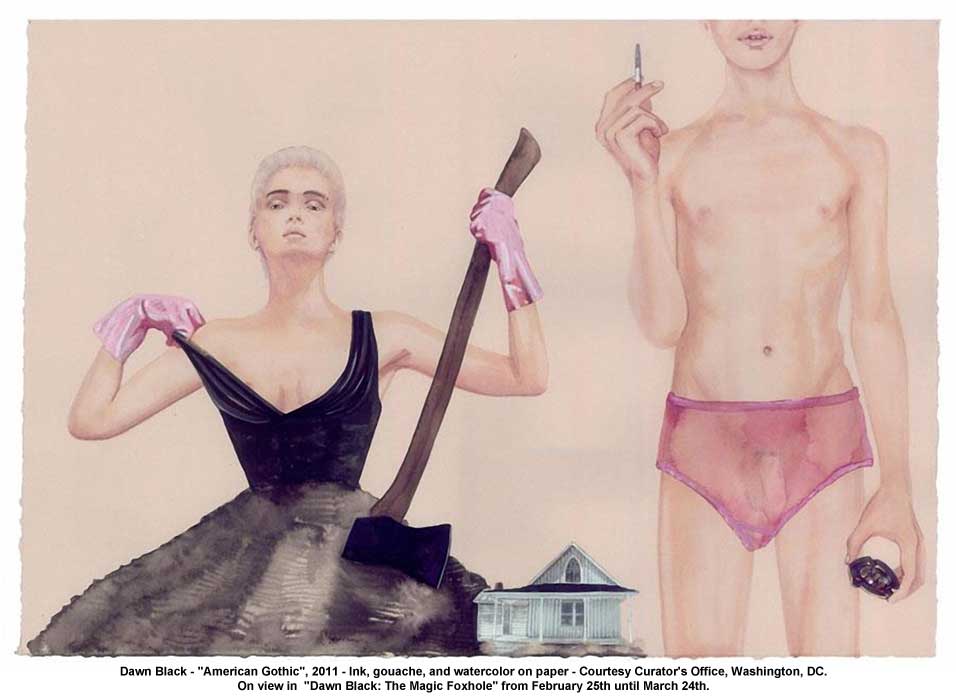

---"The Magic Foxhole" is Dawn Black's second solo exhibition at the gallery and presents works inspired by an unpublished J.D. Salinger short story, the exhibition touches upon cycles of death and folly, especially as expressed by soldiers and couture-clad women. These mysterious ink, gouache, and watercolor works on paper convey unusual narratives that have a suppressed eroticism entwined with ambiguous meditations on death and cycles of human behavior.--- Read More:http://tqarts.blogspot.ca/2012/02/ars-gratia-artis-22512.html

Alfred Kazin was an expert in bringing the charges of immaturity against Salinger’s characters in more specific and damaging ways than other critics. He accused Salinger’s Glasses of being cute, and by cuteness, Kazin meant a deliberate and calculated prolongation of adolescent winsomeness into adult life. Cute meaning superficial. With the adolescent, he felt, this winsomeness is a legitimate weapon against a world that is too much for him, but in the adult it becomes an unfair advantage. Furthermore he feels that the Glasses love only themselves and each other; for the rest of mankind, as Kazin put it, there is only forgiveness, and the author is accused of abetting and blessing this cute little wooly nest of self-love by what he called “extraordinary cherishing” of the Glasses. John Updike once said, “Salinger loves the Glasses more than God loves them.”

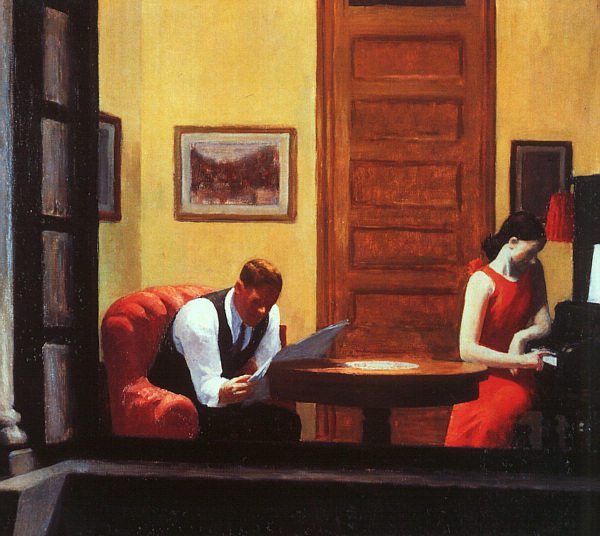

Hopper. Room in New York. 1932.---It is then that he tells her that he wants to be the catcher in the rye, someone who saves children from falling into adulthood. He wishes to catch them and return them to innocence. What he doesn't realise is that he has misheard Robert Burns' Comin' Through the Rye poem and that there is no hero that saves. He also doesn't realise it will be Phoebe who will save him from his breakdown by getting him to return home, admit he has problems and get the help he needs. The Catcher in the Rye was a book written for adults which explained to them the gap between childhood and adulthood.... To most families it didn't exist and wasn't understood, but old JD understood alright. He wrote a book that became a god damn best seller he understood so god damn well. --- Read More:http://facefortheinternet.blogspot.ca/

What irritated Updike is that Salinger not only loved his creatures but insisted that the reader must love them too. Updike very shrewdly observed that “Salinger robs the reader of the initiative upon which love must be given.” Then again, the same could be said for Charles Dickens. In the end though, most readers are not so much irritated as exhilarated, even fascinated by the near mysterious love Salinger compels from them. Something other-wordly.

To the receptive, Salinger could evoke, coax out a sense of joy, tease it out from the morass of conflicting emotions in a way that perhaps only Dickens could provide a comparable sense of well-being, not only in the characters but in the treatment of life’s humbler joys, notably food. Dicken’s descriptions of the family gathered around the festive board gives rise to a cosmic coziness that resembles the extraordinary warmth generated in the sympathetic reader by the Glasses. One longs to be part of a Glass family occasion. At the time, critic David Leitch was close to the mark in stating that the Glasses had been made to seem members of a “peculiarly intimate club, a club which Salinger readers are vertly invited to associate themselves with.”

---Kenneth Slawenski's insightful and sympathetic biography, "J.D. Salinger," convincingly shows that Salinger felt he had sinned by polluting his early work with worldly ambition. His decision to repudiate the world he had wanted to win over with his writing thus had some of the fervor of a religious quest. In "Franny" (1955), the title character cries out: "I'm just sick of ego, ego, ego. My own and everybody else's. I'm sick of everybody that wants to get somewhere, do something distinguished and all, be somebody interesting." Such desires, Salinger eventually concluded, fun da mentally contradicted his sense of writing as a sacred craft.--- Read More:http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052748704803604576078340516790196.html

ADDENDUM:

Barbara Kay:The tranquil civilian settings of Salinger’s bourgeois youth — summer camps, tony private schools, fortress-like Upper West Side apartments — provided serene external backdrops for the internal torment he brought to brilliant life. It took a certain genius to coax such widespread sympathy from the reading public for what we might call the High Class Worries of characters modelled incestuously narrowly on himself and his culturally avant-garde Manhattan peers. But he was that genius, and his cloistered exhalations set universal nerves a-shiver.

Salinger appealed to both sociologues and spiritualists. He was an urban, middle-class, Jewish, alienated John O’Hara for some; for others, a mystic whose principal motif was “the human exchange of beatific signals,” a kind of Central Park Dostoevsky.

Certainly, the slim Salinger oeuvre marks a turning point in American literary and social culture. Before Holden Caulfield arrived on the scene, maturity was something young people looked forward to with impatience and eagerness as a state in which one could set about doing things. After Catcher in the Rye, the title a reference to Holden’s evocative image of himself saving children from falling off a cliff into the abyss of sexualized adulthood, maturity began to be perceived by adolescents as a place you become “phony” (the worst sin for Salinger), a kind of death of the soul’s authenticity (which itself is

ented as a yearned-for state of being that is possible only in pre-sexualized children).Post-Holden, prolonged immaturity became an ideal, rather than a symptom of failure. But the non-sexuality part of the vision got lost in the sexual revolution. The 1970s-era result, of which Salinger must have disapproved, was a fetishization of youth combined with extreme libertinism, a rather lethal sociological combination whose negative consequences litter our cultural landscape today.

For older readers, the fictional Glass family offered a fascinating foliation of Salinger’s deepening inner conflicts. Collectively, their stories mirror Salinger’s struggle to negotiate a workable internal co-tenancy between the tantalizing non-intellectual selflessness of Buddhism and the highly intellectual, seductively egocentric “religion” of psychoanalysis, the trendy obsession of his era’s cultural elites. Read More:http://www.mercatornet.com/articles/view/j_d_salingers_american_dream

COMMENTS

COMMENTS