The refusal to accept the status quo in the universe marks not only adolescents; it also marks the saints and, at times, the mad. The connection is not accidental but necessary and functional. The young have the clarity and newness of vision, the relentless but two dimensional ogic, and the almost unbearable sensitivity that often characterize the saintly and insane. A saint as well as a madman may be an adolescent who has refused to “grow up,” who is unable or unwilling to cover his soul with the calluses necessary for the ordinary life, the crucial difference being that the saint finds a protective armor in religion while the madman’s only protection is flight. All, in different ways, wage war with the way things are; they are martyrs to the commonplace.

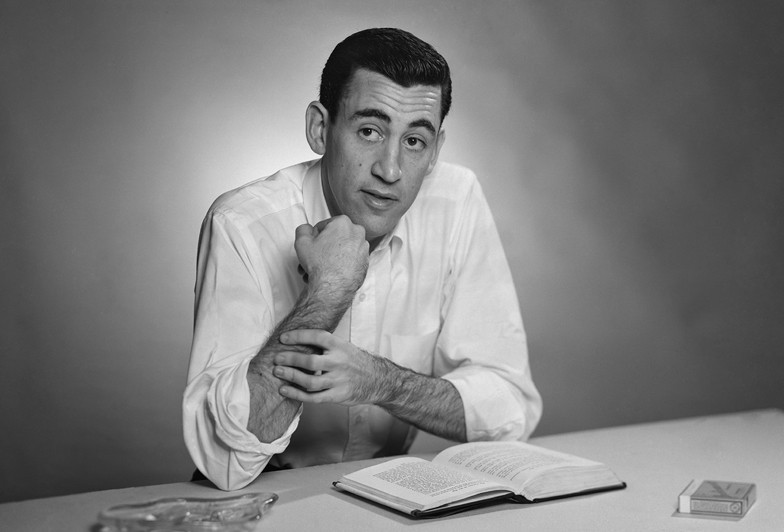

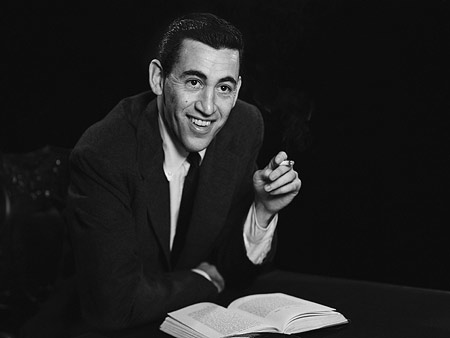

—Today, thanks to a newly released biography by Kenneth Slavenski, (J. D. Salinger – A life), we get to know that the legendary writer was a war hero of World War II spiritually tormented by what he had witnessed. Using military records as a source, Slavenski reveals to us that Salinger was among the soldiers who landed in Normandy on D-Day and among the only 563 survivors of the 12th Regiment originally made of 3.080 members. Made prisoner by the Germans, he managed to survive thanks to the fact that he could speak German fluently after spending 10 months in Austria living with a family of Jewish origins. Once the war was over, he tried to search for such family only to discover that they had all died in a concentration camp, including their young daughter who is believed to be the writer’s first love. It is said that Salinger was obsessed with privacy and Slavenski seems to have found that the reasons for it is to be traced back in his childhood spent with parents who never discussed with the son their past or the difficulties they experienced due to their mixed marriage.— Read More:http://www.vogue.it/en/people-are-talking-about/last-short-notes/2011/01/salinger-biography

If Holden Caulfield in The Cather in the Rye falls considerably short of heroic stature, it is because the author has, after all, limited his range and chosen to tell, in speech, setting, and incident, the story of an adolescent. The child or adolescent cannot be the hero of a tragedy because his powers are not fully developed and his defeat or destruction, not matter how affecting, is not as pitiful or terrible as the downfall of a human being at the height of his power and glory. But the fact remains that Holden Caulfield, if he is a rebel at all, is a rebel against the human condition and as such he deserves his small share of nobility.

There have been studies, such as Halpern’s on Rockwell and earlier in The Eye of Innocence, by Leslie Fielder which effectively debunk the cult of the child, and suggest that the Original Innocence we have come to worship in them is a reaction against Original Sin through the medium of youth. The innocent child, in other words, is a myth like Jean Jacques Rousseau’s Noble Savage- savage, perhaps, but not noble. That is, there is a vampiric quality to leeching off youth and the wild and untamed.

—Then Jon Volkmer, an English professor, had what Holden Caulfield would have called a goddam terrific idea. They could establish an annual J. D. Salinger Scholarship in creative writing for an incoming freshman, and as a bonus the winner would get to spend the first year at Ursinus in Salinger’s old dorm room. “Any college could offer money,” Professor Volkmer said. “Nobody else could offer Salinger’s room.” — Read More:http://jonathanshipley.blogspot.ca/2011/03/jd-salingers-brief-stay-at-ursinus.html

Fielder was particularly fascinating on this subject because by applying Freudian theory, he wound up standing solidly alongside the orthodox theologian. Using the insights of depth psychology, albeit not the most scientific and enlightened, he reached conclusions considerably closer to Saint Augustine or Calvin than to Freud. The orthodox theologian sees sin in the infant as well as in the adult; similarly the Freudian sees sex, which of course is not termed as sin, in the infant as well as in the adult. With Original Sin replaced by Original Id, Fielder can gleefully reassert the demonic nature of the child. As he demolishes the liberals for their naivete about the innocence of child witches , one can almost see him testifying at the trials in Salem. His essay suggested a novel, kind of under the radar force at work: Freudian Puritanism.

Still, debunking “childism” did not in the end dispose of the child. It is surely no accident that in so many civilizations the child, like the fool, is assigned a special oracular authority. Nor can this be dismissed simply as superstition. It is part of humankind’s collective experience that out of the mouth’s of the young can come truth and that in the eyes of the young the world is new- or, as Wordsworth put it, Youth is “Nature’s Priest.”

All of J.D. Salinger’s work is imbued with this belief; a vague but present messianic element, the blink of an eye where in cherishing the child, we cherish ourselves, or rather the memory of ourselves in youth, and those unselfconscious seeds of redemption; emancipatory and revolutionary qualities that we had, at what we once were or thought we were. But while it is true that we sentimentalize the child and innocence, surely we also sentimentalize age, particularly middle-age and experience. If some of us are overemotional about the dewy freshness of the half-grown, surely others are equally emotional about the dry, grown-up courage that it takes to live life as it is. Compromise can be sentimentalized as much as courage, and resignation has its own lyricism, far removed from the laughter and gaiety which often masks all manner of hate, cruelty, and perverted fantasies.

ADDENDUM:

( see link at end) …In J. D. Salinger: The Development of the Misfit Hero, Paul Levine isolates Salinger’s primary concern as the plight of the individual who is out of step with society; the spiritual non-conformist is forced to compromise his integrity by participating in a pragmatic society. Levine perceives that the problem is more intricate than the simple dichotomy which French draws between phony and nice worlds when he states, Salinger’s choice for his hero is essentially a religious problem, that is, of finding moral integrity, love and redemption in an immoral world.

Kazin accuses Salinger of bearing excessive love towards his characters, and accuses the Glasses themselves of narcissism; he feels that the only epithet which suitably describes them is cute. … Most of the critics represented in Grunwald’s anthology cluster in the centre of what he suggests is an ideological and philosophical spectrum: David Stephenson sits on the extreme left with A Mirror of Crisis in seeing Salinger as a sociological writer whose theme is the individual versus conformity; Josephine Jacobsen represents the far right in claiming that Salinger’s key objective is the pursuit of Wisdom,…Other critics have discussed his use of the child; there is general agreement that the overtones of Wordsworth’s image of the child trailing clouds of glory are unmistakable, and that the child functions as a symbol which

supply the adult intellect with the inspiration for which it vainly seeks within itself.Several of Salinger’s more perceptive critics deserve closer attention. In Seventy Eight Bananas, William Wiegand argues that Salinger presents the drama of the individual consciousness in its struggle to maintain the correct discrimination and critical perspective. He sees the Salinger hero as striving for invulnerability; having rejected impulsive suicide as a cure in A Perfect Day for Bananafish, and having illustrated the futility…

…Wiegand is quite right to show the dimensions of Salinger’s search for a means whereby the sensitive intellect may rationalise its position in an apparently absurd world, where characters such as Walt and Allie meet untimely deaths. However, Wiegand implicitly criticises Salinger for not having offered a permanent “remedy”, and his conclusions are as unsatisfactory as those of J. T. Livingston,who feels that this apparent rejection of alternatives furnishes grounds for the belief that “Salinger shows that reconciliation with both society and God is possible only through the courageous practice of Christian l0ve.

Rather than adhere to one school of religious thought, Salinger turns to many different religions and philosophies in an attempt to answer the problems which trouble him. Most critics who have seriously faced the problems posed by Salinger’s fiction have attempted an analysis of

its religious dimension, but this has too frequently been undertaken in a cryptic and perfunctory manner. However, Gwynn and Blotner feel that Salinger is “probably the only American writer of fiction ever to express a devotional attitude toward religious experience by means of a consistently satiric style”, and a growing number of critics have felt that Salinger’s most serious meaning, and deepest personal interest, lies in the area of religion. Read More:http://digitalcommons.mcmaster.ca/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5830&context=opendissertations&sei-redir=1&referer=http%3A%2F

COMMENTS

COMMENTS