Finding behind the laughter all kinds of hate, cruelty and perverted fantasies. In a way, the Glasses are an intimate club, as David Leitch once said, a peculiarly intimate club in which Salinger’s readers were overtly invited to associate themselves with. …

It is this clubbiness which provokes the objection that the Glasses love each other and themselves at the expense of others: the rest of the world is shut out. One does indeed get the feeling that there is an invisible barrier between the Glass living room and the rest of the universe and the Glass children themselves are very much aware of this. When Zooey accuses himself and the others of being freaks, there is no reason to think that he does not mean it-or that Salinger does not mean it. Their cleverness, their cuteness, their sensitivity, irritates them quite as much as it irritates us at times, in their being too sensitive to live in society. Or, perhaps the opposite is true; perhaps they are too sensitive to ignore it, to look the other way, to withdraw, as well-adjusted, busy, adult people withdraw into their protective shells when faced with society’s terrors.

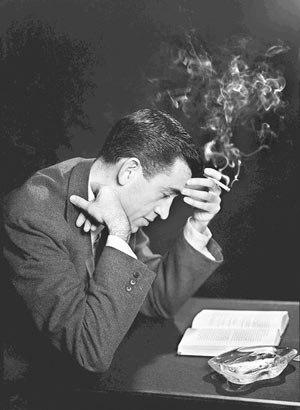

---Up until the mid-fifties, J.D. Salinger had been circling around the eldest child of the Glass family, Seymour. Seymour appeared as the main character in the short story “A Perfect day for Bananafish”, but for the most part he stayed in the background. At the time of Franny and Zooey he was already dead. But in almost every Glass family story, Seymour was a presence: the soul, conscience and genius behind Les and Bessie Glasses’s large troupe of precocious children. Now, in twin novelllas packaged in one volume, and appearing in in 1963, Seymour gets top billing. But because these are Salinger novels, Seymour does not come out and speak or perhaps do a little soft shoe for our amusement. Instead, the stories are narrated by his Boswell, his brother Buddy Glass, and once again Seymour is one degree removed from the action of the stories.---Read More:http://www.litkicks.com/category/series/seeing-salinger

Like Holden Caulfield, the Glasses simply cannot accept the injustices, the ugliness, the lovelessness, and the egomania that surrounds them. It is true that Holden and the Glasses dislike phonies too much, are too perturbed by all the people who are in Franny’s words, “so tiny and meaningless and sad-making.” But that is, after all, the very condition which Zooey is trying to cure in his sister- and in himself. At the end of the story, after he has tried for hours to argue her out of her disgust with the world, he tells her the famous parable of the Fat Lady. It goes back to the time when the Glass children were quiz kids on a radio show and their wise, good, poetic, and revered brother Seymour made the youngsters shine their shoes before each performance, even though no one would see those shoes.

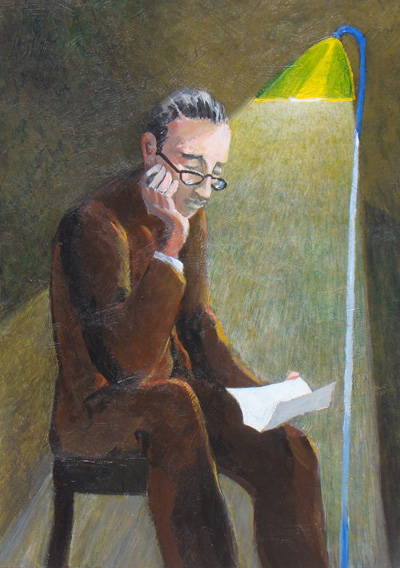

---If Holden Caulfield was the headliner, the Glass family chronicles were the holy text, their teetering balance of intellectual and spiritual, of the mighty and the mundane a heady brew for anyone trying to live a life of high drama and actual worth. His characters painted their nails, pushed off their shoes, sat in the tub, lighted a cigarette, petted the cat, drank a glass of milk, lighted another cigarette, but to a man, woman and child, they sought and passionately believed in a state of understanding greater than their own. Call it God or grace or spiritual enlightenment, every story, every character lived and breathed at the glowing edge of something larger. For all his arched-brow cynicism, Salinger was just as sentimental and religious as C.S. Lewis.---Read More:http://articles.latimes.com/2011/may/01/entertainment/la-ca-salinger-20110501

It had to be done, said Seymour, for the Fat Lady- the incarnation of all the lonely, unlovable, unlovely people who presumably sat listening by their radios. And then Zooey drives home the point: “Are you listening to me? There isn’t anyone there who isn’t Seymour’s Fat Lady…Don’t you know that? Don’t you know that goddam secret yet? And don’t you know- listen to me, now- don’t you know who that Fat Lady really is…Ah, buddy. Ah buddy. It’s Christ Himself. Christ Himself, buddy.” With that, Franny is, apparently, appeased and goes serenely to sleep.

ADDENDUM:

Barbara Kay:For older readers, the fictional Glass family offered a fascinating foliation of Salinger’s deepening inner conflicts. Collectively, their stories mirror Salinger’s struggle to negotiate a workable internal co-tenancy between the tantalizing non-intellectual selflessness of Buddhism and the highly intellectual, seductively egocentric “religion” of psychoanalysis, the trendy obsession of his era’s cultural elites….

The seven Glass family children — Seymour, the family guru who commits suicide, Buddy, the writer and Salinger’s alter ego, BooBoo, the well-adjusted one (the only one happily married with children), Walter and Wake, the twins, one a priest, one killed in war, Zooey, the most handsome and dramatic, and Franny, the beauty and would-be saint — are the offspring of an Irish-Jewish marriage (like Salinger’s parents) in which gregarious Irish volubility and moralistic Jewish introspection are both ratcheted up to fever pitch.

The Glasses are pre-hippies: out of synch with the conforming majority, but not proud of that. They are happily American, very attached to their roots and concerned to fit into the mainstream of American life, albeit on their own exalted terms. They have no use for the passivity of E

rn religions, even though they strive to embody the uncorrupted love ethic they promote.All the Glass children have their different issues, as we would call them today, but they are united in their epic quest to love without ego, and their collective, ongoing mourning over Seymour’s never-explained suicide. Zooey complains they are all “freaks” because Seymour educated them in the ways of true love and then deserted them.

In their own way, the Glasses were attempting to forge a new, postwar American Dream, not through ideology or social engineering, but through a marriage of high intelligence and high spiritual sensibility. Their litmus test for success is the achievement of harmony in human relationships, the only subject that really stirred Salinger’s creative juices, perhaps because it remained so elusive in his own life.

Several generations of readers evidently have shared the same longing — which is why Salinger lives on as a nostalgia figure, if not a prophet. Unless and until inner peace becomes the new American norm, his niche in the American canon is secure. Read More:http://www.mercatornet.com/articles/view/j_d_salingers_american_dream

COMMENTS

COMMENTS