The atmosphere conjured up by J.D. Salinger inevitably recalls the era of nineteenth-century romanticism; then, too, the promise of utopia disappeared in blood, leaving the younger generation disillusioned and ready to escape into the personal search for truth and beauty. But despite their incessant sentimentality about death, the nineteenth century’s young romantics were more vigorous, more eccentric, more public in their yearnings than the counterparts of Salinger’s time.

Nowadays, a Byron going forth to fight the Ottoman in Greece might still be applauded, with some reservations, but his drinking wine from a skull would most likely be dismissed as a phony, inauthentic gesture. Today, we might have strong strains of neo-romanticism, post-romanticism, the locus of which is a more private, limited romanticism, more given to the small gesture than to the great adventure. Like by day agitating on behalf of the Palestinians in the Judean Hills but supping and sleeping in Tel-Aviv. Perhaps there is more a tending to introspection than to the big dream, and in a sense the enduring appeal of Salinger is that knack for continuing to fit that mood, that the seeds of the grand are found in the private and intimate.

But this mood has a lot of mileage behind it. The American young have always been more sheltered than those of other civilizations and certainly, historically, less concerned with politics, although that cycle appears to be disrupted, the American version remains unique in that for centuries, the European student has taken their place on the barricades. We have had our Zinn’s and Chomsky’s but Anarchism and deep socialism do not find a natural habitat in America. It is fringe social capital for the most part. The Zisek’s and funny accents seek representation in superficial and diluted Marxism of a James Cameron and Naomi Klein, a sort of vampiric feeding or nibbling on the European carcass. With all due oversimplification, youth led riots have always been a significant and familiar, too familiar factor in European politics without genuine equivalence in the United States. With all due oversimplification, it still holds that in Europe revolutions are made by the young, but in America it is the middle aged that move the needle and change the schedule of the train.

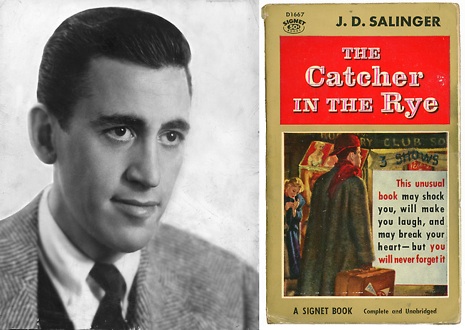

—Mr. Salinger’s literary reputation rests on a slender but enormously influential body of published work: the novel The Catcher in the Rye, the collection Nine Stories and two compilations, each with two long stories about the fictional Glass family: Franny and Zooey and Raise High the Roof Beam, Carpenters and Seymour: An Introduction.

Catcher was published in 1951, and its very first sentence, distantly echoing Mark Twain, struck a brash new note in American literature: If you really want to hear about it, the first thing you?Ѣll probably want to know is where I was born and what my lousy childhood was like, and how my parents were occupied and all before they had me, and all that David Copperfield kind of crap, but I don’t feel like going into it, if you want to know the truth.—Read More:http://www.dangerousminds.net/comments/j.d._salinger_dead_at_91

The revolutionary political and social literature of the twenties and thirties was in part written by young men, but it was not overly treasured by youth. The writers who stirred young readers were always the romantics, the nonsocial, nonpolitical ones from Cooper to Hemingway to Fitzgerald. After decades of the political, the social and the psychological novel, the young could only feel relief when they met Salinger. His adventures may be small, his battles all interior, but the gleam of delight in his eye is unmistakable. It is the gleam of a romantic.

“Delight” is not a proper critical term, but delight is what Salinger has to offer the halfway sympathetic reader, including the young. Salinger is not so much a depicter of life, as one who celebrates it,which is probably a realistic characterization of the humor and the love in his work, if not of the darker patches in “Seymour.” Ultimately, the most serious charge against Salinger was that his output was too small; that his Songs of Innocence do not reach us often enough. There is a feeling we needed more Salinger fiction, not to feed the industrial entertainment complex, but to start a few more celebrations, if only in their own quiet and unassuming way.

ADDENDUM:

( see link at end) …J. D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye belongs to an ancient and honorable narrative tradition, … the tradition of the Quest…. Holden’s Quest takes him outside society; yet the grail he seeks is the world and the grail is full of love. To be a catcher in the rye in this world is possible only at the price of leaving it. To be good is to be a “case,” a “bad boy” who confounds the society of men…. The flight out of the world, out of the ordinary, and into an Eden of innocence or childhood is a common flight indeed, and it is one which Salinger’s heroes are constantly attempting. But Salinger’s childism is consubstantial with his concern for love and neurosis. Adultism is precisely “the suffering of being unable to love,” [Dostoevsky] and it is that which produces neurosis. (Arthur Heiserman, James E. Miller Jr., “J. D. Salinger: Some Crazy Cliff”)Read More:http://kosmosidikos.blogspot.ca/2011/02/alchemical-catcher-in-rye.html

And, from the same link above, and somewhat unsettling if not disturbing, there are intrinsic qualities to the work which are volatile and defy being pinned down,sometimes akin to a genie escaping from the bottle, much like the seeds of the counter enlightenment being found in the Enlightenment; a complicity of sorts, albeit antagonistic:

The most well-known event associated with The Catcher in the Rye is arguably Mark David Chapman’s murder of John Lennon Chapman identified with the novel’s narrator to the extent that he wanted to change his name to Holden Caulfield. On the night he shot Lennon, Chapman was found with a copy of the book in which he had written “This is my statement” and signed Holden’s name

ter, he read a passage from the novel to address the court during his sentencing….After John Hinckley, Jr.’s assassination attempt on Ronald Reagan in 1981, police found The Catcher in the Rye among half a dozen other books in his hotel room….

The film Taxi Driver (1976) follows Travis Bickle, who seems to be a representation of Holden Caulfield, only older and more confrontational. The list of similarities is long, from analyzing the fact that both of them obsess over women and try to protect the innocence of children, to the fact that both of them purchase a prostitute without actually having sex with her. They both live in New York City, and though they only see all of the filth in the city (as they are incredibly pessimistic), and vow to leave, neither of them actually departs….

In Conspiracy Theory (1997), Mel Gibson’s character is programmed to buy the novel whenever he sees it, though he never actually reads it.

In the movie Conspiracy Theory, Mel Gibson is a taxi driver and mind control victim obsessed with buying copies of The Catcher in the Rye, whose outlandish theories turn out to be correct. Through decades of essay assignments, we have been conditioned by the public school system to believe that Holden Caulfield is merely a delusional child who refuses to face the realities of life. And this is true, in a certain sense–it is the mote in one’s eye that is always most grievous, and a “caul” (Caul-field) is a thin membrane that covers a newborn’s head after birth. Actually, one’s evaluation of Catcher hinges entirely on whether it is read as a tortured adolescent projecting his own inadequacies onto others, or whether these others are themselves only parts of himself. (We will cleave fully to the esoteric reading.) From a psycho-alchemical perspective these shadows are precisely what Holden must confront and overcome. Ultimately, both esoteric and exoteric are true (this is the great illusion of Maya), and in the last chapter of Catcher, Holden will fully embrace this unity in a final state of Awareness–one where “you start missing everybody.”

… all legitimate religious study must lead to unlearning the differences, the illusory differences, between boys and girls, animals and stones, day and night, heat and cold. (J.D. Salinger, Franny and Zooey)

COMMENTS

COMMENTS