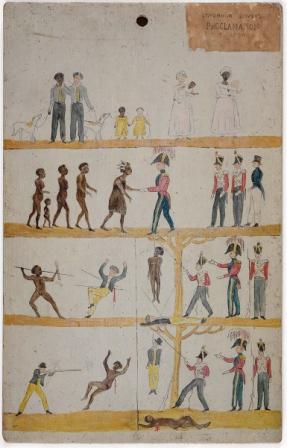

…But when Europeans settled in Tasmania, the relationship soon changed. Almost at once the Tasmanians were defined as enemies, actual or potential. One summer day some eight months after the establishment of the camp at Risdon Cove, the convicts and their keepers looked up to the surrounding heights and saw a large group of aborigines, including women and children, advancing in a black semicircle out of he woods. What their intentions were, we shall never know. One eyewitness thought they were merely herding kangaroos, another reported that they were singing and carrying green boughs as tokens of friendship.

—George Augustus Robinson was Chief Protector of Aborigines in Van Diemen’s Land (Tasmania) between 1829 and 1838. These papers are an account of Robinson’s activities in brokering peace between the settlers and Tasmania’s Aboriginal groups.—click image for source…

Still, they must have looked an eerie lot, loping out of the bush into that gloomy gully, and the young lieutenant in charge ordered his soldiers to open fire. Several aborigines were killed, several more wounded, an orphaned black child was brought into camp and hastily baptized, and so, soon after the first European settlement in Tasmania, a precedent of distrust was set.

As the white colony grew in numbers and confidence, the original Tasmanians found themselves treated more and more as predators or vermin. The free settlers wanted land, and ruthlessly drove the nomads from their hunting grounds. The shifting riffraff of bushrangers and sealers used the black people as they pleased, for pleasure or for bondage. By the 1820′s horrible things were happening on the island. Sometimes the black people were hunted just for fun, on foot or on horseback.

—Posters erected in Tasmania in the early 19th century. The posters aimed to communicate that blacks and whites would be treated equally by the British justice system. —click image for source…

Sometimes they were raped in passing, or abducted as mistresses or slaves. The sealers of the Bass Strait islands established a slave society of their own, employing the well-tried disciplines of slavery- clubbing, stringing up from trees, or flogging with kangaroo-gut cat-o’-nine-tails…( to be continued)…

ADDENDUM:

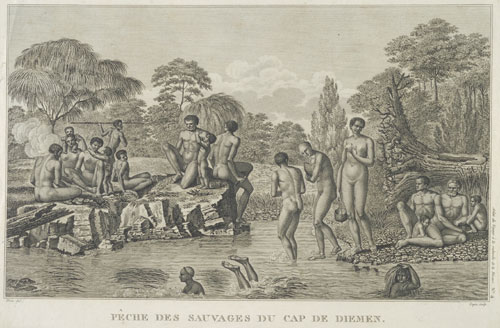

(see link at end)…No Tasmanian aborigines were seen during this first visit although traces of a human presence were noted.

The French fleet left Tasmanian waters on 28 May 1792 and, continuing the search for La Perouse, headed for the Pacific and Australia.

Eight months later, desperate for fresh water, the fleet returned to Tasmania and anchored on 20 January 1793 in Recherche Bay for a 5-week stay.

It was during this second visit that some contact was established with Tasmanian people. D’Entrecasteaux noted that if he had stayed a little longer, he would have had the opportunity “to acquire interesting insights into the lifestyle of human beings so close to nature, whose candour and kindness he felt contrasted so much with the vices of civilization.” However, the expedition’s main task and interests lay not with the native Tasmanians but with cartography. The opportunity was passed up when the

le fleet left Tasmania on 21 July 1793 with d’Entrecasteaux making a final comment(The Tasmanians) …are interesting men in every respect, with whom I would have liked to have spent all the time we have been forced to remain at this anchorage.

Despite the apparently limited contact, d’Entrecasteaux noted that the possibility of polygamy in Tasmania had lead to some debate among the expedition members, but that ultimately the question could not be resolved. It was also noted that the language of the Tasmanians of Bruny Island was the same as that of the Tasmanians living on the mainland.

D’Entrecasteaux’s account is also significant because it supports the archaeological evidence that Tasmanian Aborigines did not eat fish (see The Ancient Tasmanians).Read More:http://www.andaman.org/BOOK/chapter52/text52.htm

COMMENTS

COMMENTS