Rejection as a virtue. Horatio Alger. His fable of the noble orphan who found a rich Daddy appealed to boys of all ages. The question is how did it ever get mixed up with the American myth of success? There is a myth embodied in the name of Horatio Alger, Jr. It is of course the myth of the poor boy struggling upward from rags to riches by luck and pluck, goaded on by a boyish determination to strive and succeed. Anyone born in the slums who becomes a captain of industry or merchandising is sure to be labeled an Alger hero.

But the myth embodied in Alger’s name, the American dream of success, is not the myth we find in his books for boys, if they are read attentively, and it is certainly not embodies in the career of the author. About that career, there is surprisingly little that is known beyond question. One of the best biographies about Alger, by Herbert Mays, was written in 1928, when Mays was a very young man and it is likely loaded with errors and inconsistencies at the few junctures where it can be compared with dependable information from other sources. Much of it is based on Alger’s private diaries, which since Mayes parsed them, mysteriously vanished into thin air. Nobody knows how many books Alger wrote.

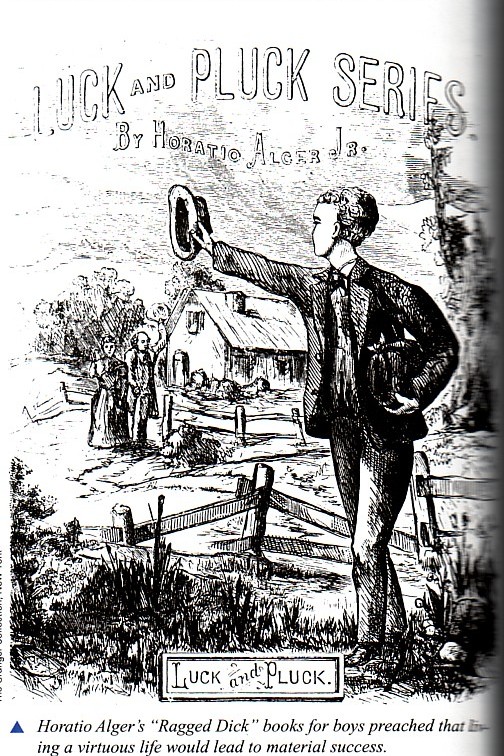

Mayes compiled a list of 118 titles, and there are later lists of up to 143, but the only volume of ”Who’s Who in America” that appeared during Alger’s lifetime tells a different story. Presumably Alger himself, or, if he was too ill at the time, his married sister, who was nursing him, had a chance to correct the entry that follows his name, and part of it reads as follows: Author. Ragged Dick series. Tattered Tom series; Luck and Pluck series; Atlantic and pacific series, etc. in all about 70 books, mostly juveniles, of which nearly 800,ooo have been sold. ”

Alger died in 1899, the same year the entry appeared, but dozens of books attributed to him were published afterwards, in some cases up to 1908. The publisher bought the right to the name and used the previous works as a template to be written up anew by salaried employees. He was faithfully read by a wide audience and for over forty years his dreams had become standard currency. Thousands of boys wrote to the author for advice, since they had come to regard him as a model of business acumen and avuncular wisdom. They would have been surprised to learn that Mr. Alger, in life, had been a most unhappy boy and that he had never grown up.

Alger was born in Revere, MA in 1832 and his father was a pastor of the Unitarian church in the neighboring town of Chelsea. His father was a tyrannical man who made him read Plato and Josephus in translation at the age of eight, and taught him Latin at nine. His schoolmates at Gates Academy called him Holy Horatio. During his senior year at Harvard he fell in love with a girl named Patience Stires, but Horatio Sr. persuaded her to break the engagement. Horatio got the writing bug after reading Moby Dick which had just been published.

His first steps toward a literary career were teaching in boys’ schools, writing pieces for the Boston papers, then helping to edit a new magazine that lasted only a few weeks. Left without resources, he surrendered to his father and entered the Harvard Divinity School. But he rebelled on graduation day. He received a legacy from an eccentric old gentleman whom he had befriended, and hurried off to Paris. There he became the lover of a cabaret singer named Elise Monselet, whom he had met while paying a tourist,s visit to the Morgue. Elise had literary tastes. She worshipped Victor Hugo and adored Henri Murger, the author of ”Scenes de la Vie de Boheme”. When Murger died at an early age, January 1861, she and her lover sat in a cafe holding hands, the tears streaming down their cheeks.

Soon Alger sailed home, partly because his legacy was spent, but also to escape his second mistress, an English harpy who had snatched him away from Elise. On three occasions he tried to enlist in the Union army; twice he broke his arm before being enrolled and the third time he nearly died of pneumonia. He was reccued by his father, who finally prevailed upon him to be ordained. In 1864, he became pastor of a little Unitarian church in Brewster, on Cape Cod.

However, Alger had not forgotten his literary ambitions, and he spent much of his time writing novels for boys, his Campaign series, instead of sermons. After less than two years he resigned his pastorate and went to New York to dream of unfading laurels while leading the life of a needy hack. His next novel for boys, ”Ragged Dick”, deals with the rise to respectability of a homeless bootblack. There were thousands like him in New York after the Civil War, when drummer boys and war orphans ran wild in the city streets. Alger’s book drew attention when it was serialized in a boys magazine edited by the famous Oliver Optic.

The superintendent of the Newsboys’ Lodging House, Charles O’Connor, sought him out, gave him a room at the house, and became his closest friend for thirty years, besides providing him with what he regarded as his real home. A Boston publisher, A.K. Loring offered him a contract for six books about Ragged Dick and his friends, all to be written in twenty months. After that, Alger thought, he would stop writing juveniles and engage in ”fine writing”.

Meanwhile Alger was trying to live in the fashion of romantic novelists he had seen from a distance in Paris. He sometimes disguised himself in a long cape and a tousled wig and wandered through the Manhattan streets, looking for material, he said. One spring evening during his second visit to Paris, the inspiration came, and Alger worked on his great novel most of the night. In the morni

e sent an urgent message to Una Garth, a married woman with whom he had fallen in love. She wrote in her diary that the Lord should spare him of knowledge of his own incapacity and Alger put aside his great work, while he wrote another juvenile, ”Struggling Upward” which turned out to be the average quality of all his books for boys.

Then, tired of struggling with the Muse and rejected by Mrs. Garth, he temporarily lost his mind and was carried screaming to a hospital. When he recovered, Alger once again took refuge with Charles O”Connor and continued writing books for boys. A very few of his novels were written with a social purpose. ”Phil, The Fiddler” , one of four reprints, is a memorial to the crusade that Alger led against the ”padrone” system, by which hundreds of street musicians brought to New York from Southern Italy were kept as virtual slaves. Their parents sold them to a ”padrone”, who fed them scantily, lodged them in cellars, beat them, and took their earnings. The book helped make the system illegal.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS