“To render my works properly requires a combination of extreme precision and irresistible verve, a regulated vehemence, a dreamy tenderness, and an almost morbid melancholy.” All his life Hector Berlioz tried to set the musical world straight and win acceptance for music that ”sets in vibration the most unexplored depths of the human soul. ” But mostly, he frightened everyone.

When Berlioz is mentioned, there is always an inventory of slanders and half-truths that circulate as the standard Berlioz cliches. From the very beginning of his career Berlioz had tried, unsuccessfully, to defend himself against tedious misconceptions: no, he was not a composer of program music dependent on literary explanations; no he was not a hysteric specializing in bizarre effects; and no, he was not obsessed with grandiose spectacles and overblown orchestrations. Once when his friend Heinrich Heine described him as ”a clossal nightingale or gigantic lark, a creature of the antediluvian world”, Berlioz had explained, very patiently, that only a handful of his works, notably the ”Requiem” , called for ”colossal” effects; the rest were ”conceived on an ordinary scale and require no exceptional means of execution.”

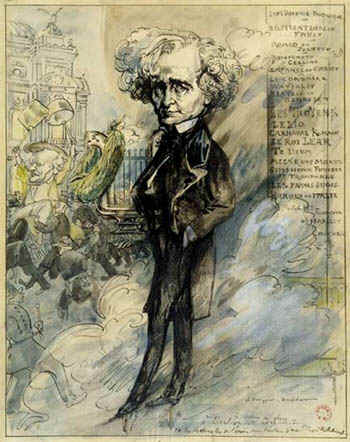

![berlioz2 Artist: Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard, 1803-1847) published in L’Illustration, 15 November 1845 This cartoon was also published in Louis Reybaud, Jérôme Paturot à la recherce d’une position sociale (Paris, 1846). The caption reads: “Heureusement la salle est solide... elle résiste !” [Fortunately the hall is solid... it can stand the strain!]. A copy of this cartoon is in the Musée Hector Berlioz.](/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/berlioz2.jpg)

Artist: Grandville (Jean Ignace Isidore Gérard, 1803-1847) published in L’Illustration, 15 November 1845 This cartoon was also published in Louis Reybaud, Jérôme Paturot à la recherce d’une position sociale (Paris, 1846). The caption reads: “Heureusement la salle est solide... elle résiste !” [Fortunately the hall is solid... it can stand the strain!

Paris certainly had never known a composer so deeply committed to the idea of music as an art that ”sets in vibration the most unexplored depths of the human soul”. Like Beethoven, who had described himself as a bacchus pressing out the grapes that make men spiritually drunken, Berlioz wanted to awaken a whole world of feelings and sensations that had not even existed before. On such a serious quest there was no time to be wasted on trivia; which may have been one of the reasons he had no use for Rossinni. His elective affinities were with other men of great themes and passions: Goethe, Byron, Shakespeare, Virgil, Faust, Romeo, the Aeneid. Rising on the romantic literary landscape, his sun illuminated only the highest peaks of the range.

berlioz. Artist: Étienne Carjat published in Le Diogène, 12 February 1857. A flamboyant manner, and flamboyant music made Berlioz and apt subject for satirists.

”The dominant qualities of my music are passionate expressin, inner fire, rhythmic drive and the element of surprise,” he writes in his Memoirs, and it is precisely these qualities that make his works so difficult to perform and hard to understand: ”to render them properly the performers, and especially the conductor , ought to feel as I do. They require a combination of extreme precision and irresistible verve, a regulated vehemence, a dreamy tenderness and an almost morbid melancholy, without which the principal features of my music are either distorted or completely effaced. It is, therefore, as a rule, exceedingly painful to me to hear my compositions conducted by anyone but myself.”

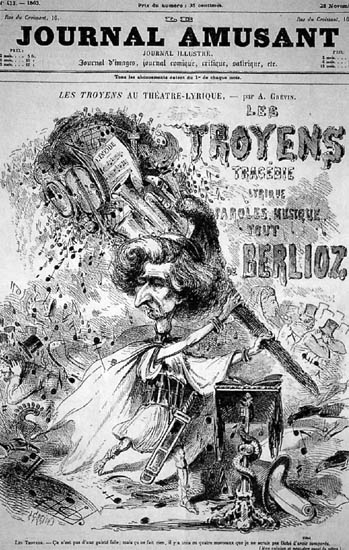

www.hberlioz.com:''Artist: A. Grévin published in Journal amusant, 28 November 1863 The Journal contained cartoons, drawn by Grévin, related to the last three acts of Berlioz’s epic opera Les Troyens (Les Troyens à Carthage), the only part of the opera performed in the composer’s lifetime''

No one else on the scene had Berlioz’s grasp of the orchestra as a great socio-musical instrument , as a vast organ of sound producing enterprise. He was the first great conductor, and also the first great orchestrator, because, as Liszt observed, he possessed the ”most powerful musical brain in France”. Unlike his colleagues, who were accustomed to working out a composition on the piano before arranging it for orchestra, Berlioz always conceived his music orchestrally from the ground up. By the same token, it is impossible to give a clear idea of his scores by playing them on a piano. When he was a student, prize juries at the Conservatoire jdged orchestral entries on the basis of piano auditions, and Berlioz forfeited several important awards because his efforts were either pronounced unplayable or mutilated in performance. ”For instrumental composers,” he said ruefull

COMMENTS

COMMENTS