The cannibal in written records was originally a story about what existed beyond the boundaries of the known. It kept the wild and the civic state apart. Sometimes, however, it brought them together: Othello seduced Desdemona with his tales

of the Cannibals that each other eat,

The Anthropophagi, and men whose heads

Do grow beneath their shoulders. This to hear

Would Desdemona seriously incline,

But still the house-affairs would draw her thence,

Which ever as she could with haste dispatch

She’d come again, and with a greedy ear

Devour up my discourse.

”Probably the most famous of all shipwrecks that included cannibalism is the one of the brigg Medusa, which was documented by two survivors, Henri Savigny and Alexandre Correard, in their famous book and also in an important painting by Theodore Gericault (pictured above). Of the 370 people on board of the Medusa about 150 climbed onto a self-fabricated raft. After spending several night hip-deep in the water and fierce and deadly fights between different parts of the shipwrecked, cases of madness and hallucinations, mutiny and murder, hunger drove the shipwrecked to cut pieces of deceased seaman and eat them. Also the two authors of the documenting book partook of the gruesome meal. All in all they spent more than two weeks on the raft untill finally 15 survivors (of the 150!) were rescued. The rest had died some way or other.”

''In many parts of the world, anthropologists have discovered that many cannibalistic tribes have usually incorporated many different forms of cannibalism into their way of life. It is not at all uncommon for one particular culture or tribe to practice a mixture of ritualistic, endocannibalism and exocannibalism, as well as resorting to cannibalism for survival and what is known as epicurean/nutritional cannibalism, which is basically the consumption of human flesh purely for the taste or nutritional value. ''

Still, for all the sophisticated thought-experiments and relativism of Renaissance thinking and Enlightenment philosophers,Robinson Crusoe’s initial visceral horror at the sight of cannibals enjoying human flesh isn’t far removed from the modern tabloid fascination with Armin Meiwes, or the audience’s shudder of delighted disgust when Hannibal Lecter dips into the brain of his dinner guest to source the cervelles au beurre noir he is about to serve him. Cannibalism isn’t only an intellectual tool for discussing political science. The taboo thing seems to be quite strong. Sleeping with relatives and eating one of your own remain a no-go zone which seems to hold an avid fascination when they come, occasionally, to light.

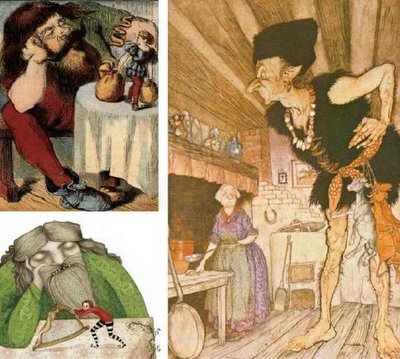

The repressed savage in us would still lurk dangerously in our unconscious, ready to be titillated, horrified and excited, by those in whom the suppression has failed, if Freud had anything to say about it. His version of the social contract has the horde of brothers killing and eating their father in order to get to the women he has kept from them. Fortunately or otherwise, a strangely human guilt accompanies the incorporation of the father, and he sits hard on our base lusts and hungers. Repressively hard at least most of the time. The eating of and becoming the introjected other work wonders for civilisation. In Maurice Sendak’s Where the Wild Things Are, in which Max, having answered his mother back with ‘I’ll eat you up,’ is sent to bed without any supper and travels to the land of the wild things:

''It’s not so much a mask as a jail cell for Hannibal Lecter’s mouth, but it’s by far one of the most terrifying ones on this list. It physically restrained Hannibal from eating people’s faces, but it never did contain him for long.''

”Then all around from far away across the world he smelled good things to eat so he gave up being king of where the wild things are. But the wild things cried: ‘Oh please don’t go. We’ll eat you up – we love you so!’ And Max said: ‘No!’ The wild things roared their terrible roars and gnashed their terrible teeth and rolled their terrible eyes and showed their terrible claws but Max stepped into his private boat and waved good-bye. And sailed back over a year and in and out of weeks and through a day. And into the night of his very own room where he found his supper waiting for him. And it was still hot.”

''Archaeological evidence for documented cannibalism associated with the mass ritual killings of the is also now coming to light. Accounts of the Aztec ceremonies describe how choice elements, such as the heart and good leg meat, were eaten ritually at the élite level, with the remainder being cycled down through descending social levels.''

The Raft of the Medusa is a vast painting—193 inches high, 282 inches wide; it hangs, with other large canvases of that period, in one of the Louvre’s grand galleries. It has darkened with time. Some of its figures are barely visible, and many details are occluded, but it’s still best appreciated in person.The Raft of the Medusa by Theodore Gericault. Adrift in mid-ocean, 150 castaways struggled and died until only 15 remained alive. Out of a scandal that rocked France,

ericault created a pictorial ”J’Accuse” that was also his finest work.

Géricault (1791-1824) revolutionized the depiction of real events, taking for his subject a scandal only a few years old and "romanticizing" it. While the painter visited hospitals and morgues to study the moribund and cadavers, the figures on the raft here hardly look as though they have just suffered through dehydration, starvation, cannibalism and madness. They are muscular. Some are beautiful.

Until the second decade of the 19th century, action painting in France—whether dealing with mythic, religious or historical events, and even if violent in content—often lacked real energy. In France, the gorgeous colors and symmetries of Poussin in the 17th century, the chiseled nobility of David in the late 18th and the shellacked beauty of Ingres at the start of the 19th all gave way to the explosion of Romanticism. One painting, above all, might be said to have initiated the new movement: Théodore Géricault’s “The Raft of the Medusa,” based on a real event and unveiled at the Salon of 1819.

The Medusa, a naval frigate, ran aground off Mauritania in July 1816. Only about 250 of the 400 people on board could fit into the lifeboats. On a jerry-built raft about 150 of the others were set adrift, left to struggle to survive, while the higher social classes easily reached safety in their lifeboats. By the time of their rescue 13 days later, only 15 were still alive. The event caused a scandal at home and abroad owing to the perceived incompetence of the ship’s captain which reflected on the entire Bourbon regime.

'': A frightful but nevertheless truthful, cruel emergency of hunger and pestilential trouble which happened in such a way in the country of Reissen (Russia?) and Lithuania in the year 1571.''

”As the first modern history painting ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ retains its immediacy the more we learn about the actual events that gave rise to it. This new interpretation implicitly shows why ‘The Raft of the Medusa’ still retains its power as the Romantic masterpiece par excellence, as well as marking the beginning of the modernist spirit in Western painting. At its heart is an ambiguity of perception on several levels, including the perception of its creator and of those who viewed it when the ‘Raft’ was first seen at the Salon of 1819. Ostensibly a modern history painting cast in the language of Michelangelo, the subject matter is in itself as ambiguous as the representation of the minute ship on a distant horizon – though in the early studies and related works, the Argos appears proportionately much larger. Why, in the ‘Raft’, did Géricault make the Argos so inconspicuous that it is almost invisible? The appearance of the vessel, experienced repeatedly as a mirage, drove the shipwrecked victims to further hallucinations. Some said they were going to get help, or believed the sea was a wine shop, before plunging off the raft to their deaths. Alhadeff shows this condition to be what was then defined medically as Phrenetis calenture – ‘Presence of an Absence’ – the manic experience of delusion from which only a handful of those shipwrecked would survive. The experience of seeing something unique in nature that does not in fact exist, along with the subject of madness itself, is a defining feature of Romantic art. It also provides a new context for Géricault’s pictorial interests in insanity and his portraits of the mentally ill.”

The men on the raft were a cross-section of the forgotten people of Restoration France; old soldiers who had fought for Napoleon and were now for lack of employment at home, being shipped off to the colonies; convicts recruited for service in fever-stricken outposts; petty clerks, hospital attendants, construction workers, sailors, a twelve year old cabin boy….Standing, there, unable to move, half in the water and half out of it, they suffered from a strange king of claustrophobia amid an infinite expanse of open sea. On the first day, burned by the African sun and pounded by the long Atlantic rollers, they consumed their entire food supply, but for a time their main concern was simply staying on the raft.

The inevitable thinning out process began after the first night, when several men were swept overboard and another dozen crushed to death by the constantly shifting timbers of the raft. On the second day, though the sea was calm, some threw themselves off the rafdt in despair; others began suffering from hallucinations. When a new and more violent storm broke that night, dozens lost their footing and were drowned. Many of the soldiers and sailors mutinied at the same time. One group fell on the wine casks and in their drunken fury tried to kill the officers gathered near the center of the platform.

''...The theory is given some credence by the tendency of some modern serial killers to indulge in practices commonly associated with the attack of a werewolf, such as cannibalism, mutilation and attacks revolving around natural events such as the cycle of the moon. ''

Soon there was hand to hand fighting along the length of the raft. Correard, a civil engineer to elected to stay with his workers rather than the safety of the lifeboat, rallied the officers and his loyal troop of employees in what was rapidly becoming a mad model of the nineteenth-century class struggle; the rank and file plebs versus the officers and the clerisy. During the attack the mutineers actually succeeded in throwing the water casks and two wine casks into the sea. By the time peace was restored, more than sixty men had been killed or washed overboard, leaving the survivors much needed room. An d now they were only knee deep in the water.

The mutiny had also solved their food problem, after a fashion. The living fell upon the dead and began eating. The officers with their more delicately conditioned feelings at first refused to touch human flesh. Instead they tried eating leather belts and cartouche cases. But on the fourth day they learned to eat sun-dried human flesh dressed with bits of flying fish that had got entangled in the raft. Feeling their strength revive, the soldiers of the African battalion worked up to another outbreak of violence . ”soon after the fatal raft was covered with dead bodies , and flowing with blood…”

It isn’t hard to understand why, for some, the cannibal of theoretical discourse, delicately or ravenously dining on his enemies, ancestors, colonisers, spiritual converters, god, lovers, or the last remaining source of sustenance is, like the preposterous single footprint that alerts Robinson Crusoe to lethal man-eating others on his island, all the more exciting for his improbability. The theoretical cannibals are so much better to think with than domesticated, actual Armin Meiwes. Actual cannibalism messes with the programme. For political scientists, or historians of ideas and the ever troubled clan of anthropologists, the sated anthropophagus offers a bellyful of moral, political and social philosophy to ruminate on.

Having started out as a mythic monster in uncharted places, the man-eating savage was presented during the Enlightenment as a description of a state of nature by those who were not in it, and who wished retrospectively to investigate the implications of natural law for the origins of the political state. The cannibal also greatly troubled the theologians, who worried about what would happen come the resurrection if particles of an eaten man co-existed with the body of the eater. Which soul would the single available body of the cannibal clothe? Would a man or woman eaten by a lion come back to eternal life even though their parts were consumed and atomised? Certainly, the Christian martyrs must have hoped so.

by raphael. ''The stark echo of womb and tomb, the perpetually tragic Mother and Son, the sacrificed lamb of God, the cult of sacred suffering and sacred Paschal blood, the barbaric cannibalism repeated in the Eucharist, are colors from the paint pot of Aries, the emblem of origins."

Eventually, the cannibal got laughed out of the philosophical arena by the Enlightenment and anthropological relativism, and has come in our time to reside either in the demented minds of characters who now entertain us in movies and popular fiction, or in those who, finding themselves in company on isolated mountains or dense jungle, put aside their squeamishness and eat to live. Sometimes, of course, they advertise on the internet.

Catalin Avramescu, a paid-up Hobbesian, it would seem, regrets the passing of the pre-Enlightenment cannibal:

”The anthropophagus was an unyielding creature who brought to light the law of a harsh and profound nature. As such, perhaps he has something to tell us about ourselves, the people of a time in which nature has become merely an occasion for the picturesque. In relation to us, the subjects of technologically mediated organisation, the cannibal of the state of nature allows us to explore this impossible dimension, to traverse the crystalline sphere of the political… ”

Only a few travellers had seen these monstrous, man-eating men – so they said. They were etched onto the empty spaces on the maps, and mentioned in the same breath as the unipeds and dog-headed creatures who also inhabited such regions outside the civilised world. Marco Polo mentions them, dog-headed and cannibal, and Columbus wrote that the man-eaters of the New World indeed had dog-heads – he is possibly responsible for their name, mishearing, it’s said, the word ‘carib’ as ‘cannibal’. For the most part, the anthropophagi of elsewhere were elaborations of travel literature heard and read, boastful, racy and imaginative as reports from a world away can hardly be these days. Even before the Enlightenment there were doubts about their veracity or the travel writers’ interpretations of what they claimed to see.

For Hobbes the cannibal was a very useful part of his thought experiment. The war of all against all would be at its most virulent where pre-social individuals ate each other when they met. And they would, because, as well as being driven by fear, ‘all have the right to all things,’ and that would include the nourishing body of the weaker other. Obviously, logic would require a contract for survival. How could a cannibal society maintain itself? It would be only a matter of time before the many became the one, and the hungry one at that, all others having been eaten. The cannibal is the savage who lacks reason, a man of nature, the very opposite of the civic men who think about him.

What the civic men began to worry about was whether it wasn’t their moral duty to conquer those savages and save them from the crimes they committed against nature, while at the same time appropriating their land and resources. The cannibal is a very fruitful concept for the conquistador who also wants to put himself right with God. The debate about the right to declare war on cannibals, once he had trembled at their terrible reality, was a question that came to Robinson Crusoe’s mind. The Spanish ‘barbarities’ against the Indians in America were not justifiable, he eventually concludes. They were ‘very innocent People’, he thinks, even if they did have ‘several bloody and barbarous Rites in their Customs, such as sacrificing humane Bodies to their Idols’, while the behaviour of the Spanish in ‘rooting them out of the Country’ was a ‘mere Butchery, a bloody and unnatural Piece of Cruelty, unjustifiable either to God or Man’.

Crusoe, the man who decided not to live his life in the ‘middle state’ his father wanted for him, fetches up on his island and over more than 25 years experiences his own conversion from solitary savagery to civilised colonialism. Though his first response to the cannibal other is almost to die of terror and revulsion, he learns to think more broadly about local habits, even if in some places they happen to include eating people.

Locke and Rousseau had a use for the cannibal too, implicating him in the need for a contractual society and seeing in him the righter of the wrongs of the corrupted civil world. Father Labat in Journeys to the Islands of America justifies cannibalism as ‘a wholly extraordinary act on the part of these peoples; it is rage that drives them to this excess, because they cannot fully avenge themselves upon the Europeans for the injustice done to them when they were driven from their lands except by killing them, when they catch them, with greater cruelty than is natural to them.’ Swift famously offered the Irish their own children to stave off the famine brought about by English landowners, as well as the suggestion that a well-suckled babe would make a fine meal for the landowners themselves ‘as they have already devoured most of the parents’. And Avramescu summarises and quotes Voltaire, from the Dictionnaire philosophique (on ‘Resurrection’), who pre-empts both the movie Spartacus and the banner ‘We are all foreign scum’ on the 1968 Grosvenor Square march:

”Man and other animals feed on the substance of their predecessors, because human bodies turn to dust and are scattered over the earth and into the air. Thus they are assimilated and become ‘legumes’. There is not a single man who has not ingested a tiny piece of our forefathers: ‘This is why it is said that we are all anthropophagi. Nothing is more reasonable after a battle: not only do we kill our brothers, but after two or three years we shall eat them, after they have put down roots on the battlefield.”

Primitive communism and the Marquis de Sade naturally found much that was good in cannibal societies: where property is theft the ownership of one’s own body is negated when it becomes a foodstuff for a hungry comrade, and the natural state where all eat all is the most radical egalitarianism or institutional collapse that any revolutionary might hope for. ‘Now, and only now,’ Lenin wrote in a letter of 1922, ‘when they have started to eat human flesh in the regions where there is famine … is the moment in which we can (which means we must) confiscate the goods of the Church with the most savage and merciless energy.’

For Sade, eating the other, that most forbidden food, is a perfect expression of desire, freedom and incorporation. Minsky, a Sadean Russian giant, discourses on the relative manners of Africans, on the one hand, and American, European and Asiatic, on the other: ”After I hunted men with the former, I drank and I ate with the latter, and I fully fucked the latter, I ate people together with the Africans. I have preserved all these tastes, and all that you see here are remains of people I devoured.”

From the “subversive image of the subversion of the moral order” , the cannibal became figured as the “universal human being,” driven by physical necessity and the scarcity of food to acts that offended his own moral order, as much as that of European societies. As hunger ceased to be a common social experience in the West, Catalin Avramescu concludes his intellectual history, so too fascination with cannibal peoples waned, having “exhausted their theoretical fruitfulness” . Cannibal stories fell away, as theories of natural law were abandoned, and political science began increasingly to rely on the positive science of law and to employ purely utilitarian and political terms to construct their models of the philosophy of law.

The idea of the savage other, outside the civilizing forces of the sovereign and religion, fell to the background of European concerns, as a new “monster” entered the imagination: the state. As the modern state fell increasingly under critique, under the influence of Enlightenment ideals, the history of human politics and power became more and more broadly framed as a succession of savage brutalities, beside which exotic tribal customs could not hold their place of fascination.

”Cannibalism, which recieved its name only when Columbus landed in the Carribean, is connected with seafaring throughout history. Already Odysseus, during his zick-zacking across the Mediterrenean, had to experience how members of his crew were torn apart and eaten alive. But cyclops didn’t do it out of necessity or distress, but from lust and greed, and thereby became the ancestor to those cruel wild people that started to shock and fascinate the minds of the old world during the time of the big discoveries. One of the greatest discoverers of them all, the most famous Captain Cook was killed and eaten in Hawaii. This gave the man-eater a function, by seperating civilisation from barbary: “He who eats a man, is no man.” But the disgust has a janus’ head, especially in studies and salons around the capitals of Europe, because the same wild people also became the ideal for mankind in its primary principle. This way the view to relativity towards our own society was opened.

Already in 1580 Michel de Montaigne demanded in his essays (I, 30, Des Cannibales) that it is “more barbaric to delect oneselve at the terminal pains of a living man than to eat him dead; more barbaric to tear an all-feeling body on the torturer’s bank, to roast him bit by bit, let him be bitten and eaten by dogs and pigs [...] and, what is even worse, all under the disguise of true belief and piousness, than to roast him and eat him after he has died.”

Fee! Fie! Foe! Fum! I smell the blood of an Englishman. Be he 'live, or be he dead, I'll grind his bones to make my bread.

Cannibalism from necessity therefore was morally less reprehensible and was tolerated; in the early 19th century this measure amongst shipwrecked seafarers, was so common, that survivors regularly had to asservate that the hadn’t taken to this means as it was commonly suspected of all half-starved shiprecked seamen. Moreover no lawbook in the civilised world had a paragraph about eating a deceased member of your own species, more so since all of those nations were obeying to a ritus – in more or less figurative amounts – that was metaphysical cannibalism focused on the founder of their religion.

Probably the best documented case of cannibalism at sea occured in 1710 on the english merchant ship Nottingham Hill in front of the coast of Maine were it ran onto a riff. After three weeks of misery the carpenter died and one seaman suggested to eat the body. “After long and intense thought and discussion about the sinfulness of such acting on the one hand and the absolute necessity of it on the other hand”, wrote captain John Dean, “beliefs, conscience and so on had to bow down to the irrefutable arguments of our hungry stomachs.” But not always did seaman in comparable situation stake to the most ultimate measures. When the brigg Polly on her journey from Boston to the Carribbean was demasted by a storm and the ship ran halfways full of water and drifted rudderless through the Atlantic for 191 days, none of the dead were eaten. Nevertheless they kept their more lucky colleagues alive, because the survivors cut them into pieces, fixed their body parts onto hooks and this way were able to catch enough sharks to remain alive until they were found.

The situation became morally more complex if there was no dead body available for eating. For the first time in the early 17th century a historical case is documented, in which seven Englishmen were driven from the shore of St. Kitts in the Antilles out onto the open sea and drifted there for two weeks, when one of the shipwrecked had the idea to decide by drawing lots, who should be eaten. By all means the lot fell onto the men who made the suggestion and after a second lot decided who the henchman would be, he was killed an eaten.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS