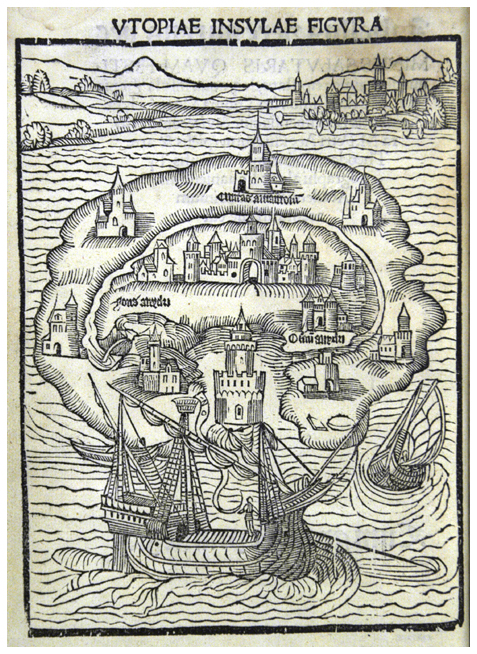

”A few years ago, I told an English professor (who regularly teaches Thomas More’s Utopia in his Renaissance literature courses) that I was preparing to give a paper at a conference of the Society for Utopian Studies. He asked me where the meeting was scheduled to take place. I answered, “Montreal.” We discussed other matters for a while and then, just as I was about to leave his office, the professor said to me: “Yo realize you gave the wrong answer to my question.” “What question?” “About that Utopian Society’s meeting. The right answer should have been nowhere.” He smiled. “The utopians meet nowhere, eh?”

It was a time of social change, and such periods seem to incubate and hatch notorious charlatans. The Protestant reformation challenged established spiritual hegemony and permitted the beginning of some cultural, political and economic fragmentation as the reverberations of the Italian Renaissance slowly established itself in Europe. Utopianism captured the imagination of many; the belief in attaining perfection, a final state, a form of alchemy that would convert scarcity to abundance. Utopia – literally “nowheresville” – was the name of an imaginary republic described by Thomas More in which all social conflict and distress has been overcome.

When Charles V of the Holy Roman Empire learned of the murder of Sir Thomas More by King Henry VIII, he stated: "If I had been master of such a servant, of whose doing I myself have had many years no small experience, I would rather have lost the best city in my dominions than lose such a worthy councilor."

The study of utopias is riddled with contradictions. They are admired and equally feared. They are a radical critique of the societies that surround them, and yet they are in some ways the archetypal product of those same societies.The Utopian vision has always been plagued by a duality at cross purposes; the vision is sold on the ecstasy of the ends and not on the means by which to arrive, which presumes the power of the vision is sufficient. Secondly, it attracts both dreamers and dissenters who generally cannot peacefully coexist. The humanist ideals of More, Reginald Pole and William Latimer were based on the ancient classics such as Plato’s Republic and a brand of Christian Cabala which seemed incompatible with the religious dogma and repression of their time. Thomas More wrote Utopia in 1515, looking forward to a world of individual freedom and equality governed by Reason, at a time when such a vision was almost inconceivable.

“in Utopia, where every man has a right to everything, they all know that if care is taken to keep the public stores full, no private man can want anything; for among them there is no unequal distribution, so that no man is poor, none in necessity, and though no man has anything, yet they are all rich; for what can make a man so rich as to lead a serene and cheerful life, free from anxieties.”

”A serious dilemma presented itself as a result of this newfound devotion to the ancient sages because of the apparent conflict between pagan classicism and Christian doctrine. It became a matter of deepest concern for all Renaissance thinkers to find an accommodation of the two doctrines — the philosophy of Plato and the teachings of Christ. As a result of their dual allegiance, we get the term which describes the movement, “Christian humanism.” The successful adaptation of double devotion is seldom better illustrated than in the works of Thomas More, especially in Utopia.”

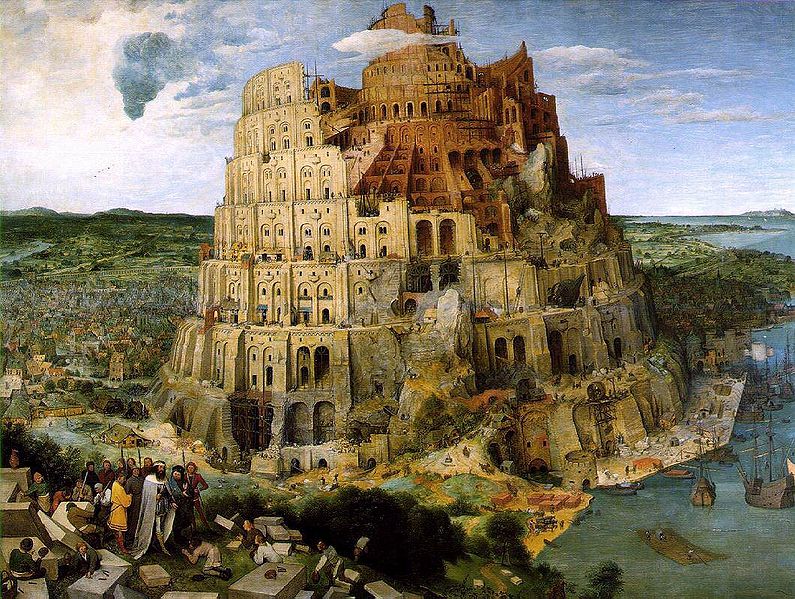

The holy terrors of Munster. They were the Anabaptists, the extreme and perhaps lunatic fringe of the sixteenth century, and they staged a revolution that anticipated the ”psychic epidemics” of our own time. In the long record of man’s savagery to man, there can be no more brutal episode than the drama of the Anabaptist revolution played out in the small city of Munster in northwest Germany in 1534-35. There, as the medieval world was dying and the modern age dawning, as an ancient social order disintegrated and a new proletariat was born, starving and desperate men conceived a utopian kingdom of eternal goodness and eternal peace, and ended by creating a forerunner of the modern totalitarian state.

Anticipating the French Revolution by more than two hundred and fifty years, and the Nazis and the Communists by nearly four hundred, the Anabaptist revolution in Munster was striking in its modernities of class warfare, thought control, communal farms, an elite military corps, and a proto-Gestapo. The Anabaptist leaders were brutal fanatics; believing that the world was an abomination of corruption, they were determined to destroy it.

Within the walls of the city, Jan of Leyden had proclaimed himself the Anabaptist king and messiah. Determined to destroy the institutions of private property and marriage, he presided over a mounting orgy of political terror and sexual license. Sitting in the market place, surrounded by two hundred courtiers and fifteen wi

he passed judgement on traitors, appeasers, and the merely weak willed, who he beheadedwith his own sword.

Outside the city gathered all the forces of the Holy Roman Empire, Catholic and Protestant alike. Acting to protect privilege and what they conceived to be God’s true order, they buried their doctrinal differences in a counter-revolutionary alliance and pledged to extirpate the Holy City of the Anabaptists by death and fire. In the end they succeeded, but not until they had matched atrocity with atrocity in the sixteen-month siege of Munster.

In some sense Martin Luther had started it all, though the Anabaptist heresy, as all rebellion, was repugnant to him. Luther had dreamed of a spiritual freedom. In his view the earthly order was trivial, a mere anteroom to paradise and hell. It was also sacrosanct, since disorder was the Devil’s work. What Luther could not see was that the medieval structure of belief he helped to bring tumbling down was a marvelously intricate web of social

relations in which lord, priest, artisan, and peasant had, for something like a thousand years, functioned in close interrelationship.

Medieval man shivered in the cold and was lucky if he died peacefully of the fever, in his bed; but unlike today’s rootless and alienated society, medieval man did not doubt his place in the scheme of things. To question the medieval dogmas was tantamount to questioning everything, and so to open the floodgates of doubt.

Lutherans might care only for the question of man’s relationship to God. But men could not question that relationship without questioning the secular law as well, simply because few men had learned to distinguish between the two. In the process of revolutionary questioning, the Anabaptists were a phenomenon that has become familiar in the modern era. They were the lunatic fringe or, perhaps more fairly, they were the radical left wing of those many others who sought a newly Godly dispensation in the world.

That the old social order was corrupt, few serious people denied. Rome, where a few years earlier a Borgia had managed to attain the throne of Saint Peter, was a scandal.

In 1490, according to the great historian Henri Pirenne, there were at least 6,800 courtesans in the Holy City. The pope and his cardinals ‘,consorted publicly with their mistresses, acknowledged their bastards,” Pirenne says, and endowed them with riches stolen from the coffers of the Church. The conduct of the clergy outside Rome was hardly better, as Erasmus and Sir Thomas More, men who had died faithful to their church, repeatedly pointed out.

”The rest of the earth, it was announced, was to be destroyed, but Münster would be spared to become the New Jerusalem.Into this volatile situation Jan Matthys entered: a tall, gaunt figure with a long black beard. His imposing, physical presence allowed him to gain power quickly, but the attempt to realize the New Jerusalem was not without authoritarian measures. Unlike Hoffman, he did not hesitate to employ violence to accomplish his purposes. On February 25, 1534, he preached a sermon at the house of an Anabaptist near a fish market. Afterwards, he proclaimed to the crowd that God ‘s grace had allowed the city to have a favorable beginning, but in order to build the republic of Christ on earth, it was necessary to purify the city of all uncleanness (Unsauberkeit), whether the impure be papists or others who dissented from the prevailing Anabaptist teachings.

To achieve this goal, Matthys advocated the execution of all remaining Roman Catholics. However, Knipperdolling, one of the town leaders, disagreed with Matthys, saying that the bloodshed would cause the outside world to be enraged against Münster. A compromise was reached and they decided to expel all the “godless” ((Gottlosen)) from the city and make those who chose to stay behind receive compulsory baptism.”

”By “Utopian,” I mean something other than the merely fantastic. Early in the 16th century, there were suppositions that what had been discovered by Colombus was Avalon, Atlantis, the Fountain of Youth, the Earthly Paradise, St. Brendan’s isle, Antillia, Prester John’s Kingdom, or the Isles of Hesperia. When it was recognized that what had been found was truly a new continent, the medieval mind of Europe surrendered its imaginary geographies, only to allow its modern significatory imagination to go to work in constructing Utopia where it had not been found. Thomas More would write his Utopia with a placid Carribean island in the background of his imagining; so too would Thomas a Campanella, with his City of the Sun , and Johann Valentin Andraea with his Christianopolis : lands more than mythical, almost tantalizingly realizable. Francis Bacon wrote his New Atlantis, suggesting that America was at once very old (heir to the traditions of the first civilization, Atlantis) and very new, a new “philosophic continent” within whose outlines lay modernity and freedom from the shackles of scholastic thought. Almost all these early 16th century Utopian writers saw America as a place where the regeneration of the age promised by the Rosicrucians and other groups might come about, home to bold experiments in the investigation of nature and society. Some, like Bacon, saw it as more ammunition in the war of the moderns against the ancients, and Colombus as the empiricist pioneer par excellence , sailing for unknown lands of the unfathomed world.”

COMMENTS

COMMENTS