”Whereas at times Marcuse’s writings on art seem to be a replay of the tendency of romanticism and some versions of artistic modernism to celebrate the artist as the true revolutionary and art as the true revolution, in fact Marcuse posits art more modestly as the helpmate of revolution” ( Douglas Kellner )

He was the prophet of the new left, an an era’s prime advocate of violence. The role of art in Marcuse’s work has often been neglected, misinterpreted or underplayed. His critics accused him of a religion of art and aesthetics that leads to an escape from politics and society. Yet, Marcuse perceptively analyzed culture and art in the context of how it produces forces of domination and resistance in society, and his writings on culture and art generate the possibility of liberation and radical social transformation. Art, alienation, and the humanities coalesce as the decisive themes of Marcuse’s lifelong work.

”For Marcuse, emancipatory art can help produce revolutionary consciousness, or the subjective conditions of revolution, but there is an unresolvable tension between art and politics, the artistic revolution and the political revolution. Although MArcuse insists on the importance of political struggle as the means to realize revolutionary hopes and imperatives, he likewise insists on the autonomy of art, claiming that the most revolutionary art may well be the most removed from the demands of political struggle. ” ( Kellner)

Marcuse, with regard to ”emancipatory art” Marcuse pitches his tent in the humanities, demarcated from the world of science and technology. In his “militant middle period” ,approximately 1932–1970, he promotes an educational activism in opposition to traditional aestheticist quietism, to which he reverts in this third period . His theoretical foundations,though questionable to many, are rooted in the Frankfurt School’s conception of alienation as reification. The critical theory was somewhat utopian but the essential plank was the decline and redefinition of the bourgeois culture under National Socialism brings about the identical inclination to see art as the victim of similar pressures in advanced industrial societies, since Marcuse believed fascism to be but one, and the most primitive technologically and politically , of the many forms of authoritarianism that serve to preserve monopoly capitalism.

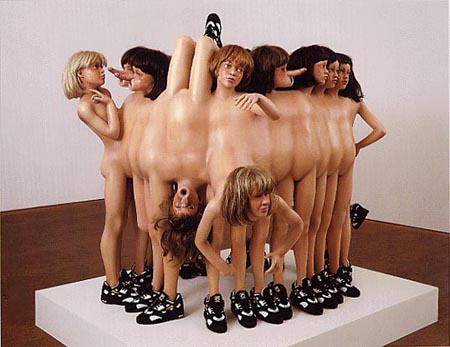

Jake and Dinos Chapman.''Genesis is driven by the same intention as sculptures such as Zygotic Acceleration or Tragic Anatomies by Jake and Dinos Chapman, visualizations of biogenetic manipulation in fibreglass. The difference to this offline-work is that in Kac’s project the users write collectively on a (metaphoric) version of the future body; which also distinguishes Genesis from Metabody where users present their real body online and Bodies© INCorporated where users write their own virtual body. ''

In his 1937 essay “The Affirmmative Character of Culture,” he attacks the quietism of the traditional role of culture, advocating instinctual gratification—not just the liberal arts, but a reshaping of life and experience . Even in this most progressive period, his aesthetic ontology is predicated on an aesthetic rationality, as opposed to science, that negates the existent. Marcuse’s “dialectic” is Romantic negation, a conception rooted in dualism, not historical materialism; art having a dual role as ideology as well as critique.

By the time of ”One Dimensional Man ” in 1964, Marcuse concluded that popular culture had obliterated the negative, that the disjunction between culture and the social order was closed, no longer to be disrupted by unruly outsiders.

In his 1967 lecture “Art in the One-Dimensional Society,” Marcuse emphasizes the liberatory power of art against the prosaic

routine of daily life. He argues that revolutions in art and culture—manifestations of the rebellious spirit of the aesthetic imagination,can fuel social-protest movements, especially in today’s advanced technological society, in spite of the danger of coop-tation.

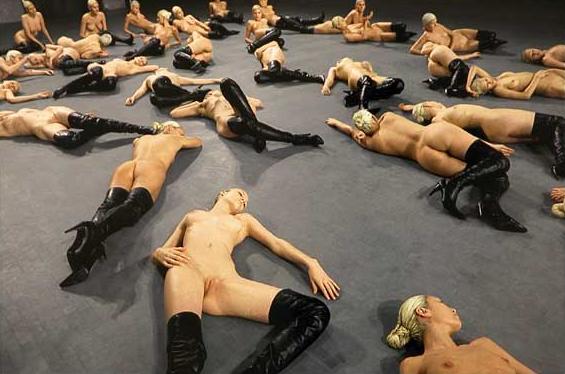

Vanessa Beecroft. ''Especially from Paris, where the shelves are still thronged with musky luxuries and one endless fashion week seems to grind into another (there are eight, I think, if you count Couture and Cruise/interseason). Haute Couture, perhaps the most extravagant example of discretionary purchasing, has been very lucratively repurposed as the face and identity of mass market perfumes. Discretionary budgets, like Satan, fulfill infinite desires. When they become undesirable in one place, or one class, they can be rehabillitated and elsewhere positioned.''

The argument of Herbert Marcuse’s ”One-Dimensional Man” ( 1964 ) is simply that the society we see around us, a middle-class, egalitarian, ostensibly humane society that provide political freedoms, ample wages , and extensive leisure time in the midst of rational technological innovation; is a pious fraud. The egalitarianism is the totalitarian egalitarianism of the middle, maintained by the savage repression of those groups marginal

advanced industrial society in its supposedly democratic, yet fundamentally deadly form.The vaunted rationality is at bottom unreason, since the society resists innovations such as automation that would inevitably free man from the necessity of enduring degrading labour and so demand the transformation of the society itself, a proposalwhich to some extent, is complementary to ideas of the Venus Project and our present transition period where AI technologies and robotics replace older industrial models which have tenaciously gripped and informed our present economic structure. To Marcuse, this rationality is unreason because, above all, the ostensibly rational economy that provides such ample wages does so by preparing for the ultimate idiocy: nuclear war.

”In our writings on the Transformation, we state that prevailing standards of living in the developed world will double in ten years and quadruple in twenty years. At this rate, the 13.67 multiple will be reached in 2048. This is a prediction we are willing to endorse. It will be the result of the implementation of state-of-the-art robotics and artificial intelligence deployed within the agricultural and industrial sectors. The inescapable corollary to this is that few jobs will remain untouched and most will simply disappear. In fact, for most people, their whole job category will be eliminated and most likely sooner rather than later. So, it seems, you will need to find something else to do. What you are doing now won’t be an option. Even if your job category remains, your employer will not. You will need to find somewhere else and some other way to do it.” ( Michael Ferguson, Polymathica )

The social humanity of the society is likewise a fraud, as are our beloved constitutional liberties, which extend tolerance only to those movements and arguments that do not fundamentally change the status quo. The very affluence that the society extends to most of its members, always remembering the wretched and the damned, such as blacks, native people,hispanics, the despairing white poor, who are excluded, is a deadening drug that keeps the all to willing victims in docility, forever barring them from achieving what people could truly be.

As Marcuse says in ”One-Dimensional Man”, The distinguishing feature of advanced industrial society is its effective suffocation of those needs which demand liberation – liberation also from that which is tolerable and rewarding and comfortable – while it sustains and absolves the destructive power and repressive function of the affluent society. Here, the social controls exact the overwhelming need for the production and consumption of waste; the need for stupefying work where it is no longer a real necessity; the need for modes of relaxation which soothe and prolong this stupefaction; the need for maintaining such deceptive liberties as free competition at administered prices, a free press which censors itself, free choice between brands and gadgets…. If the worker and his boss enjoy the same television program and visit the same resort places. if the typist is as attractively made up as the daughter of her employer, if the Negro owns a Cadillac, if they all read the same newspaper, then this assimilation indicates not the disappearance of classes, but the extent to which the needs and satisfactions that serve the preservation of the Establishment are shared by the underlying population.”

Marcuse did adjust and partially reverse some of the ardency of his radical middle period by the time his last work, ”The Aesthetic Dimension” appeared in 1978, a reappraisal first raised in his 1972 ”Counterrevolution and Revolt”. Marcuse presents essentially “a favorable reappraisal of the validity of the culture of the bourgeois era.” He speaks of art as a “second alienation,” which is “emancipatory rather than oppressive.” Here, the affirmative character of art itself is thought to become the basis for the ultimate negation of this affirmation; affirmation representing a dimension of withdrawal and introspection, rather than engagement.” This permits the artist to disentangle consciousness and conduct from the continuum of first-dimensional alienation, and thus to create

and communicate the emancipatory truth of art.” Marcuse is convinced that overtly bourgeois art,because it is art,retains a critical dimension, and should, itself, be regarded as a source of sociopolitical opposition to domination. Marcuse maintains in fact that the art of the bourgeois period indelibly displays an antibourgeois character, and in this manner he rejects the orthodox Marxist emphasis on the class character of art.

In his latter period, Marcuse also criticized the “living-art” and “anti-art” tendencies that he associates with the politically progressive art of the leftist-oriented “cultural revolution,”’ as representing a “desublimation of culture” and an “undoing” of

the aesthetic form; an explicit detour that turned away from the immediacy of sensuousness and militance characteristic

of his own middle-period aesthetic. There may well be abstract justification for Marcuse’s position In his last book, The Aesthetic Dimension. Here Marcuse opposes Marxist aesthetics and argues for the permanent value of art. Marcuse has returned to his earliest ideas: There is a dualism between art and society; art is permanently incompatible with life. Art is inherently alienated and rebels against the established reality principle .

Marcuse’s conception of education was also affected. Marcuse argued for the universality and permanence of the classics. Aesthetic “stylization reveals the universal in the particular social situation.” The historical content of an artwork becomes dated, but the universality of the forces represented transcends the particular history . While it is clear that the aesthetic ontology supporting Marcuse’s judgments could be seen as questionable, it is not immediately evident that his aesthetic principle is wrong.

Since Marcuse’s death, in the culture at large and in the specialized world of cultural criticism, cultural and social assumptions have altered so drastically that we are now aware of the vast discrepancy between our assumptions today and those current in former times and even when Marcuse wrote in the 1970s. A sophisticated analysis of what is permanent and what is dated in works of art is needed,even imperative, but Marcuse did not provide it. It is a sensitive issue, and it is unlikely that this monumental task could be undertaken without extreme acrimony and divisiveness.

The hell of the situation, Marcuse maintained, is that the ostensibly permissive but actually fundamentally repressive society so smothers dissent that alternative visions of social order are hidden from us, or cannot even be conceived by imaginations distorted and damaged by a lifetime of hidden repression:

”… it is the whole which determines the truth–not in the sense that the whole is prior or superior to its parts, but in the sense that its structure and function determine every particular condition and relation. Thus, within a repressive society, even progressive movements threaten to turn into their opposite to the degree to which they accept the rules of the game. To take a most controversial case: the exercise of political rights (such as voting, letter-writing to the press, to Senators, etc., protest-demonstrations with a priori renunciation of counterviolence) in a society of total administration serves to strengthen this administration by testifying to the existence of democratic liberties which, in reality, have changed their content and lost their effectiveness. In such a case, freedom (of opinion, of assembly, of speech) becomes an instrument for absolving servitude.” ( essay Repressive Tolerance 1965 )

Thus every reformer, indeed every individual in the society, however radical they may think themselves to be, is endangered each day in their life. In a kind of secualr transcript of Calvinism, Marcuse holds that the radical, pure in his intentions, may yet lose grace through temptation, being ”co-opted” into a society that engulfs opposition, disarming it by asserting that man, and the rebel are free.

In sum, Why did the youthful revolutionary generation of the 1960s find Marcuse’s ideas so congenial and why have his ideas proved so enduring? Does the reactionary, irrationalist passions that Marcuse imbibed intersect with the very different youth culture of the sixties on the basis of the latter’s primitivist, escapist, instinctualist tendencies? Do the two then diverge because the latter was putting into practice what the former could only theorize? Hard to say. When avant-garde and popular culture are contrasted, the issue of art as immediacy vs. alienation enters.Also, with Marcuse, the rigid opposition that grew out of the European context may not be adequate in itself when applied to American conditions, which does not exclude the pertinence of the analysis.

There is no existing framework to help decide decide when a principled refusal to participate in compromising cultural forms is warranted. When is participation in popular forms possible without being swallowed up by the mechanisms of the culture industry? Is it even possible now for an avant-garde to deploy alienation effects to break through the wall of commodity fetishism, conformity, and false values? The old avant-gardes were squeezed dry to feed the popular culture of the present; no technique seems to be left by which to defamiliarize the taken-for-granted.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Thanks for the great write up!