Henry Fuseli’s painting “The Mandrake” , now lost, struck the aging Horace Walpole as “shockingly mad, madder than ever, quite mad!” But Fuseli would hardly have regarded that as an insult. Much of the time he was trading on madness the way lesser painters exploited sunsets. For his Shakespeare illustrations he painted, among others, the mad Lady macbeth and Lear raging on the heath; from Milton’s “Paradise Lost” , to justify still another madhouse scene, he chose the vision of the Lazar house whose inmates suffer from “Daemonic Phrenzie, moaping Melancholic/ And Moon-struck madness, pining Atrophie…”

Fuseli. The Shepherd's Dream from Paradise Lost. " "...the Romantic school - An art movement and style that flourished in the early nineteenth century. It emphasized the emotions painted in a bold, dramatic manner. Romantic artists rejected the cool reasoning of classicism — the established art of the times — to paint pictures of nature in its untamed state, or other exotic settings filled with dramatic action, often with an emphasis on the past. Classicism was nostalgic too, but Romantics were more emotional, usually melancholic, even melodramatically tragic."

The way to the asylum thus becomes a pilgrimage for artists with sketchbooks under their arms. In the 1820’s Gericault, the first of the great French Romantic painters, set up his easel in the Salpétriere Hospital in Paris to do a series of ten portraits of mental patients. The idea had been suggested to him by a young psychiatrist, Dr. Georget, who book “De La Folie” had made him an authority on madness at twenty-five; Géricault intended to record the particular facial expressions associated with various types of madness-kleptomania, hysteria, criminal compulsion, and so on.

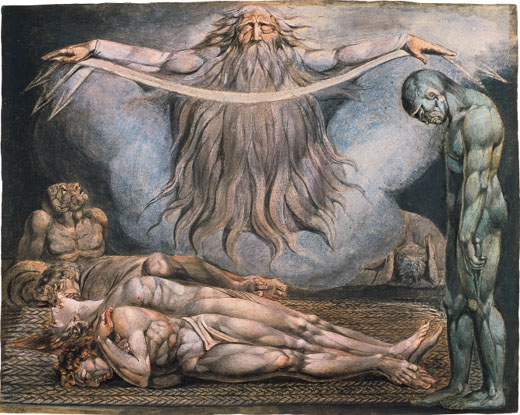

William Blake The House of Death 1795/circa 1805 Colour print finished in ink and watercolour on paper, 485 x 610 mm Presented by W. Graham Robertson 1939 The subject is taken from Milton’s Paradise Lost (1667), Book X. In a vision presented to Adam, Death hovers over a plague-house, dart in hand, teasing his victims with the promise of eternal sleep but letting them suffer further. The subject is the same as in Fuseli's acclaimed painting, recorded by a drawing shown nearby. Blake's composition is, though, much more economical and more stylised.

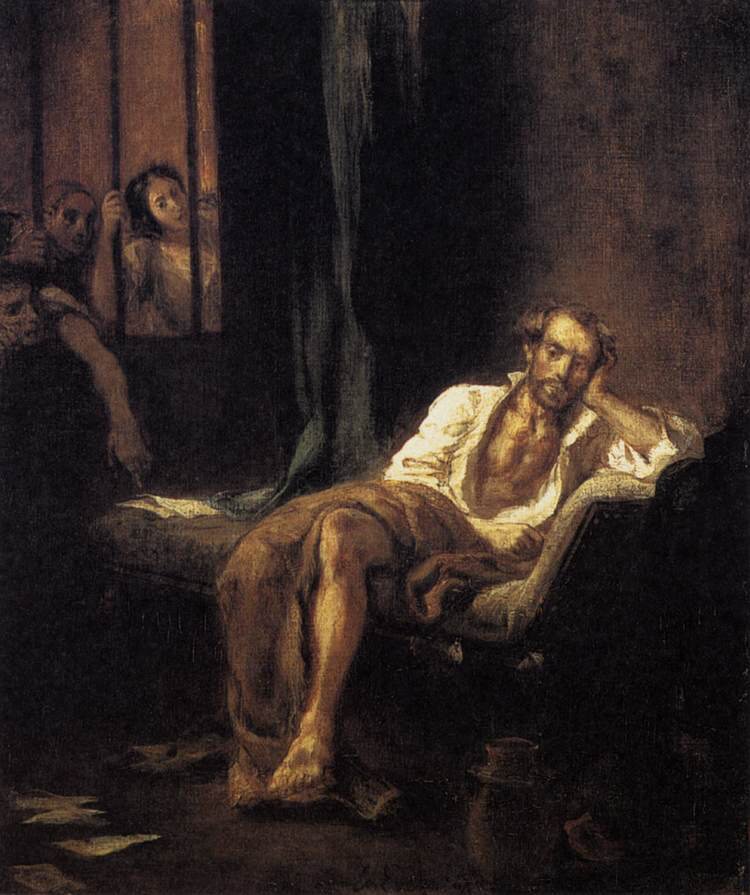

Géricault’s friend Delacroix followed his example and produced two historical paintings of “Tasso in the Madhouse” . Both show the great sixteenth century poet lost in schizoid reveries, ignoring the taunts of his fellow inmates. it is no coincidence that Delacroix’s “Tasso” bears a marked resemblance to the traditional “Christ Mocked by Soldiers.” To the romantics Tasso was a Christlike culture hero, a poet who went mad for the sake of his art.

One of the earliest German romantics, Wilhelm Heinse, was the first to write about Tasso as the exemplary madman who had fallen victim to the world’s conspiracy against love and genius. Then Goethe took up the theme, to write one of his finest dramas about him; Liszt composed a piano piece and two symphonic tone poems; Donizetti a three-act opera. Lord Byron, in “The lament of Tasso” , has the poet falsely imprisoned for imputed insanity in an asylum where he is made to suffer “Sickness of heart, and narrowness of place”:

Henry Fuseli The Vision of the Lazar House (Die Vision des Elendsspitals) 1791-1793 Pen and wash on paper, 560 x 660 mm © 2006 Kunsthaus, Zürich. All rights reserved. The subject is taken from John Milton's epic retelling of the Biblical narrative, Paradise Lost (1667). Fuseli represents the vision of the horrid future of mankind, in suffering, madness and disease. Over the heads of humanity the figure of Death, dart in hand, looms, arms outstretched. This unfinished drawing relates to the huge (3 x 4 metres) canvas on this subject exhibited at Fuseli's one man show, The Milton Gallery, in 1799.-Tate

Feel I not wroth with those who bade me dwell

In this vast lazar-house of many woes?

Where laughter

ot mirth, nor thought the mind,Nor words a language, nor ev’n men mankind;

Where cries reply to curses, shrieks to blows,

And each is tortured in his separate hell —

For we are crowded in our solitudes —

Many, but each divided by the wall,

Which echoes Madness in her babbling moods;…

Though he claims to have been sane when he came, he feels himself slowly going mad “From long infection of a den like this,/Where the mind rots congenial with the abyss…”

"After his return to France in 1821, Géricault was inspired to paint a series of ten portraits of the insane, the patients of a friend, Dr. Étienne-Jean Georget, a pioneer in psychiatric medicine, with each subject exhibiting a different affliction."

None of this has much to do with the actual life of Tasso, who was confined by the Duke of Ferrara for the defensible reason that he was insane and had to be kept out of the way of the Inquisition. But the function of the romantic artist-madman is literary, not historical; he provides access to the long-neglected darker sides of passion and imagination and helps to demolish the eighteenth-century convention that man is subject to the rule of reason.

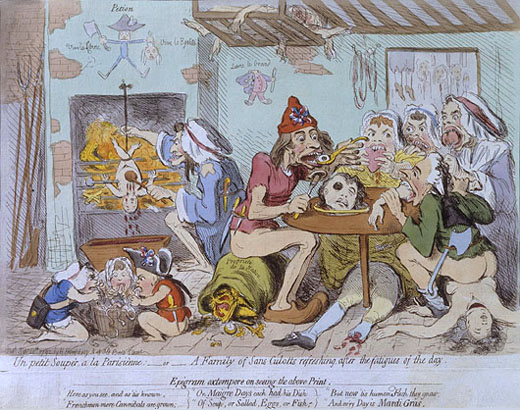

James Gillray Un Petit Souper 20 September 1792 Hand-coloured etching, 248 x 350 mm With permission of the Warden and Scholars of New College, Oxford A cannibal apocalypse: the sub-human depravity attributed to the French 'sansculottes' (revolutionaries) is manifested in a scene of bestial consumption. Men, women and children chomp down on human limbs and organs. More bodyparts decorate the rafters, and through the open door are signs of further carnage. The print amplifies news of massacres in Revolutionary France. Reports condemning these would often refer to the revolutionaries as 'cannibals'.- Tate

Madness makes all symbols possible, and the sleep of reason is one of the ways a writer can probe and expand the limits of his domain. Goethe’s Faust is the exemplary neurotic of the age, and Gretchen goes completely mad; together, with the help of their therapist, Mephistopheles, they break through to deeper psychological levels than any characters since Shakespeare’s. It was Shakespeare incidentally, who taught the romantic playwrights how sweet are the uses of insanity in the theatre. The great mad scenes in works like “Faust” and “Lucia di Lammermoor” – the frenzied laugh , the disheveled hair, the plaintive ditty sung by witless maid; all derive in one way or another from Ophelia, Lear, or Lady Macbeth.

"The Bride of Lammermoor (c.1878) Sir John Everett MILLAIS (1829 - 1896) The subject is taken from Sir Walter Scott's novel 'The Bride of Lammermoor'. Edgar, Master of Ravenswood, has just rescued Lucy Ashton, daughter of his enemy, from a wild bull. Unaware of his identity she is surprised at his cold manner. The model for Ravenswood perfectly fits Scott's description: 'A monteso cap and a black feather drooped over the wearer's brow, and partly concealed his features which, so far as seen were dark, regular, and full of majestic though somewhat sullen expression'. Millais, Holman Hunt and Rossetti had formed the revolutionary Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood in 1848. Millais was the first to return to the fold becoming an Associate of the Royal Academy in 1853 and he later turned to more sentimental and popular subjects with immense success."

There are symbols of a literary dementia that takes a tremendous toll among Bellini’s and Donizetti,s heroines. For a clinical description of a typical case we need look no further than Sir Walter Scott’s “Bride of Lammermoor” , the novel on which Donizetti’s “Lucia” is based. The story comes to a climax after Lucy has stabbed her rejected bridegroom on their wedding night and her parents find her in the chimney corner of the bridal chamber,

seated, or rather crouched like a hare upon its form- her head gear disheveled; her night clothes torn and dabbled with blood, – her eyes glazed, and her features convulsed into a wild paroxysm of insanity. When she saw herself discovered, she gibbered, made mouths, and pointed at them with her bloody fingers, with the frantic gestures of an exulting demoniac.

“John Buchan contends that The Bride of Lammermoor is atypical of Scott’s novels in that it ends tragically, with no hope for the future, its characters engulfed in a destiny beyond their control. The terrible darkness is only momentarily relieved by Caleb Balderstone’s “raid” on the nearby village of Wolf’s-hope in order to provision his master’s castle for the unexpected reception of Sir William Ashton and his daughter. Scott wrote it, as Coleridge wrote “Kubla Khan,” in a drugged and abnormal condition; in fact, having no recollection of its composition, he pronounced it “monstrous, gross and grotesque” at the completion of his first reading.”

"Torquato Tasso (1544-1595), Italian poet, one of the foremost writers and a tragic figure of the Renaissance. In 1565 he joined the court of Alfonso d'Este, Duke of Ferrara, where he wrote the first version of his masterpiece, Jerusalem Delivered (Ital. Gerusalemme liberata), an epic of the exploits of Godfrey of Boulogne during the First Crusade. He was frustrated by conditions at court, where he felt unappreciated by his patrons and envied by his colleagues. Psychologically unstable, he developed a persecution complex that led to a fit of violence in 1579. He was imprisoned in a convent from which he escaped. In 1579 he returned to Ferrara, but was confined in a madhouse, where he remained until 1586. For Romantics like Delacroix, Tasso, shut up in his Ferrarese prison, was to be the epitome of the artist-hero who suffers for his art and beliefs."

It is hardly surprising that this horror story should have been written, or rather dictated, when Scott was in an almost continal opium stupor, taking as much as two hundred drops of laudanum and six grains of opium a day to relieve the pain of a stomach ailment. Afterward, when he had recovered from both the treatment and the disease, he was unable to remember any details of what he had written, and found the results “monstrous, gross and grotesque.”

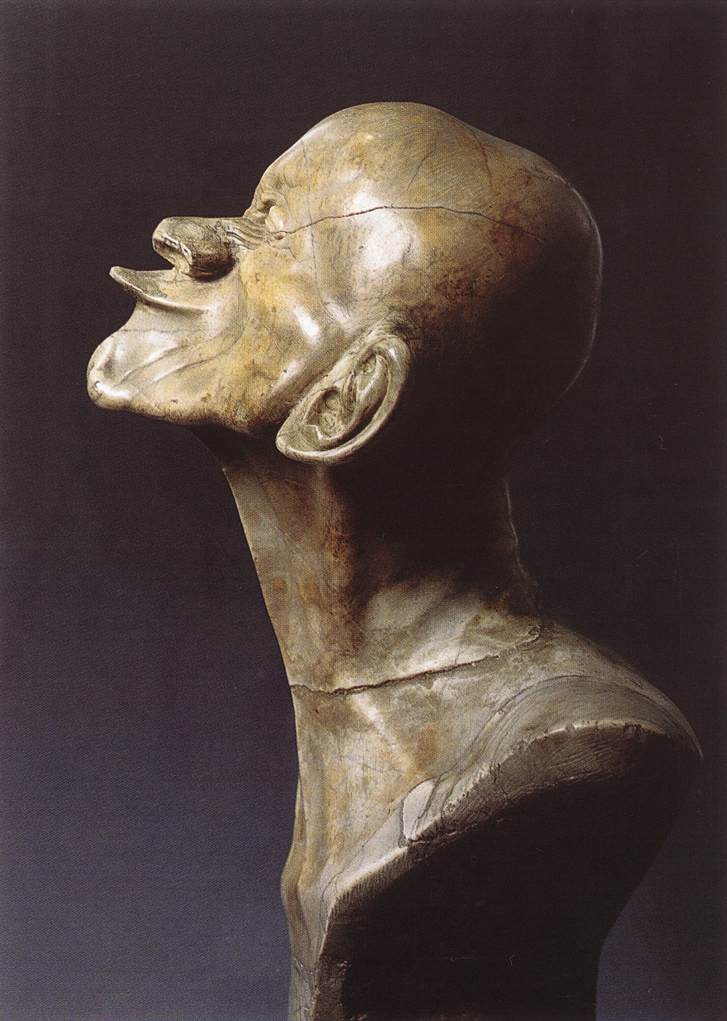

"For the Romantic painters, madness was no longer an abnormal or bizarre subject but a constituent part of humanity. Insanity and disease were portrayed by Franz Xavier Messerschmidt (1736-83), in his "character head" sculptures (1770-83), mostly modelled in lead. Francisco Goya painted himself with Dr Arrieta, as a tribute to the man who had nursed him through a long illness. He portrayed himself as a sort of Ecce Homo, with the suggestion of a crown of thorns. During the same period, the artist began his grim, visionary "Black Paintings", which show human cruelty, while expressing an understanding of the fear that could cause it. In France, Gericault produced a series of portraits of inmates at the Salpetriere asylum. With their fixed expressions, they are symbols of a disease that is an integral part of the human condition."

All the literary opium eaters- notably Coleridge, Crabbe and De Quincey- wrote about lunacy and hallucination, but they were a long way from being the only ones who were attracted to the theme: some of the most eminently sober and even-keeled of writers introduced mad scenes in their work, often as much for stylistic as for psychological reasons. On the operatic stage, where there was a near epidemic of lunacy, it afforded composers a marvelous opportunity to write delirious music for the coloratura soprano.

a

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS