The main claim is that the Romantics turned the agenda of the Enlightenment on its head with a vengeance; it was crisis in an age of reason, the somewhat logical and not unexpected reaction to a scientific age. It was the dark side of the moon so to speak. Henry Fuseli was an art of the imagination. Passionate about literature and mythology, he frequently drew his subjects from the Iliad, the Odyssey, Dante, Shakespeare and Milton. It was explorations of language, myth and history as a world of the unconscious in fantastic pictures described by the Romantic poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge as “Convulsia and Tetanus upon innocent Canvas” .

Mad Kate is the melodramatic study of a demented woman, by Henry Fuseli, the Swiss painter who transplanted himself to London in the 1760's and became part of the English romantic movement. Kate is an illustration for a poem by William Cowper, himself intermitenly mad, which features her as the village lunatic, driven out of her wits by the death of her lover. Fuseli shows her crouching on a rock, hair and dress aswirl; an apt symbol of the mad underworld of European romanticism.

“Romanticism’s cult of the bizarre found expression not only in such literary movements as Gothicism, but also in art. Henry Fuseli, a Swiss artist, thought by some to have homosexual leanings–he was known to depict lesbian scenes and females seducing men–believed that his friend William Blake, “was damned good to steal from.” Blake however rejected Academic art in favor of a private mysticism.Horace Walpole called Fuseli’s work “Shockingly mad,” with the emphasis on the mad, a characteristic that may be said to apply to Blake’s work also. The appreciation of the weird, the sublime, and the picturesque became a cornerstone of Romantic individualism.” ( Kieron Devlin )

“Shockingly mad, Madder than ever, Quite mad!” said Horace Walpole about a painting by Henry Fuseli. But the young Romantic Age had a penchant for madness; hence all the mad scenes that marked its artists’ revolt against reason. The art of the preceding epoch had elebrated the Great and the Beautiful; it was an age of equestrian statues and of paintings of gentlewoman being serenaded in pleasure gardens. But then, almost as though the French revolution had given the starting signal for this kind of terror as well, the rococo dream dissolves into the romantic nightmare, and the arts proceed to disgorge all the suppressed fears and ferocities of the human imagination.

Fuseli. The Nightmare. 1781. "In it Fuseli depicts a languidly recumbent female figure clad in a sleeping gown upon whom sits an ugly, hairy creature known as an incubus, a folklore demon believed to rape women in their sleep. Entered into the 1780 Royal Academy exhibition, the painting tended to evoke nightmares for the London critics as well. One wrote that it "...ought to be destroyed", while Horace Walpole called it "...shockingly mad, mad, mad, madder than ever." Openly erotic, the painting, nonetheless was repeated in no less than six different versions. Each of them sold practically before the paint was dry. Commercial engravers loved it, and apparently so did the public. Print reproductions of it abounded. A hundred years later, one of them ended up framed and hanging in the office of Austrian psychoanalyst, Sigmund Freud."

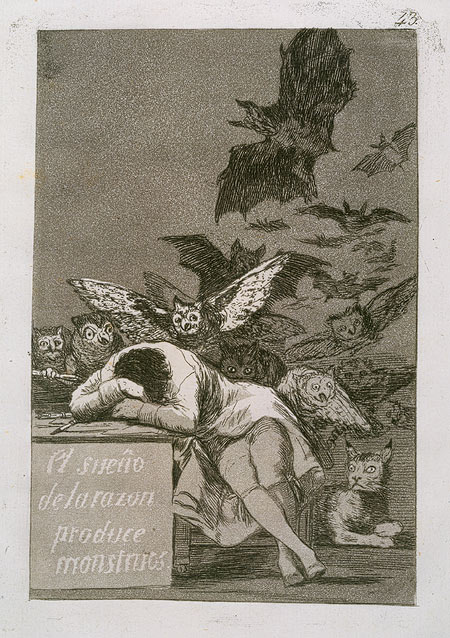

Now it is not field marshals on horseback but demons of lust who ride wildcats and broomsticks in Goya’s “Caprichos”; the only beautiful women are the ones being sold by hideous whoremongers, and the myth of a polite, perfectible society is transformed into repulsive images. Here, a century before Freud, Goyal provides the illustrations for a jungle book of the psychopathic subconscious. In the “capricho” entitles “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters” , he even shows us how it was done: a portrait of the artist as a young dreamer, haunted by the phantoms that have sprung from his own overheated brain.

The Sleep of reason Produces Monsters is Goya's title for this engraving, one of the famous Caprihos series, published in 1799.

We know that Goya had firsthand knowledge of the sleep of reason, for he went to the madhouse of Saragossa to study scenes of demonic possession among the violently insane. The result is a typically ambiguous painting known as “The Madhouse” , in which half naked lunatics perform their antics before black-robed visitors who seem, on closer inspection, to be rather more sinister than the inmates.

“The art of Swiss born painter Henry Fuseli ( 1741-1825 ) should have a privileged place in any consideration of the interrelated themes of spectacle, sensation, and the transformation of the public culture of art in late eighteenth-century Britain. Examning his art and reputation offers an opportunity to further explore what Robert Miles has described as the ‘overlap of individualism, consumerism, and the beginnings of a technology driven entertainment industry based on visual pleasure’ within this era , and the potential continuity between the historical convergence and the ‘technical-visual dystopia’ of the present age. ” ( Martin Myrone )

For half a century, spanning the period from the late 1770’s when he first came to public attention as a visual artist through to his death in 1825, Fuseli was one of the dominant personalities of the London art scene, and his art and reputation rested to a high degree on the profound institutional and discursive shists that moved art in these years toward the condition of spectacle.

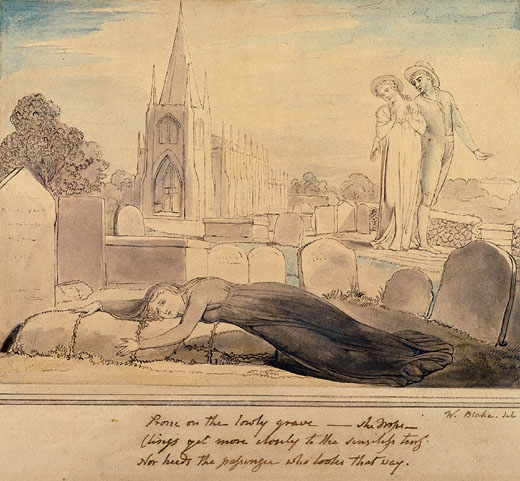

William Blake. 1805. "Widow Embracing the Turf Which Covers Her Husbands Grave:A young woman has thrown herself onto the newly-filled grave of her husband. A pair of elegant youths walking by, look piteously towards her. This design was prepared as an illustration to a new edition of Robert Blair’s poem, The Grave (1743), but was never used. Blair’s text offered

tations on mortality that struck a chord with the Gothic tastes of the time. "… Goya is a very Spanish painter, but these were not merely local lunacies, escaped from an asylum where the Inquisition still held sway and madness was regarded as a kind of “lese-majeste” against God. Throughout Europe there were young romantics who were as fascinated by the irrational as their fathers had been by the promise that reason would solve everything. The French Revolution, originally advertised as the culmination of the age of reason, had served to destroy both the old order and the belief that intellect could be elevated to take its place. Now it was the emotions’ turn to be consulted about the future of mankind.

Henry Fuseli Wolfram Introducing Bertrand of Navarre to the Place where he had Confined his Wife with the Skeleton of her Lover circa 1812-1820 Oil on canvas, 970 x 700 mm The lord of a castle shows an unseen visitor his faithless wife, secreted in a sepulchral chamber, embracing the headless, skeletal remains of her lover. A young admirer recalled Fuseli telling the story: ‘At breakfast Fuseli mentioned a picture which he had just sketched from an ancient German Ballad and promised at night to relate the Story – for he said it must be at night – “I can only tell it at night”’.

Hence the cult of feeling that arrives with the romantic quest for new forms of art and society. Passion is at a premium. Poetry, says Wordsworth in his preface to the “Lyrical Ballads”, represents “the spontaneous overflow of powerful feelings”. For Keats, all human passions are, like love, “creative oof essential beauty”. Blake says that “Exuberance is Beauty,” and as usual goes straight to the heart of the matter: “Sooner murder an infant in its cradle than nurse unacted desires.”

Richard Cosway A Nun Surprising a Monk Kissing a Nun in a Church Interior circa 1785-1800 Pencil and watercolour on paper, 199 x 162 mm Print Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations. Nuns feature heavily in the erotic literature and art of the eighteenth century. For readers in the Protestant world, the rituals and institutions of Catholicism were as titillating as much as they were morally reprehensible. Gothic novelists made the most of such associations by returning repeatedly to medieval Italy or Spain as a setting.

“Lessing was a persistent non-conformist, a free thinker whose writings form a challenge, a dramatic dialogue with a real or imagined opponent. Lessing played with pieces rich in association and thought nothing of borrowing ideas as in his Laocoon which is not so much a book about as against the visual artists. “In the Laocoon, Lessing erects a high fence along the frontiers between art and literature to confine the fashion of neo-classicism within the taste for the visual art, where indeed it remained unchallenged till Fuseli discovered the pictorial equivalent to Shakespeare in the rude sublimities of Rembrandt.”

Joseph Wright A Philosopher by Lamplight 1769 Oil on canvas, 1282 x 1029 mm Derby Museums and Art Gallery 1961-508/1 An old man in the costume of a hermit or philosopher contemplates human bones in a lamp-lit cave, while two small men or boys dressed as pilgrims (the shells in the hats identify them as such) approach with trepidation. The exact subject of this painting is uncertain; it may relate to several different literary sources. Wright has been more concerned with creating a sense of weird mystery; note the strange discrepancy of scale between the hermit and the young men.

Like Goya, Blake felt a special affinity for the creatures of the mental underworld. His engraving of “The Madhouse” presents a compassionate view of that dreaded London institution. Bedlam, where, as he says in his great poetic vision of Jerusalem, men have built “Dens of despair in the house of bread.”

His friend Henry Fuseli did a drawing of a still more theatrical madhouse episode showing a lunatic trying to escape from his warders. Based on a “real scene in the hospital of S. Spirito at Rome,” it was supposed to depict a certain psychological type whose favorite subjects are said to be “Spectres, Demons, and madmen; fantoms, exterminating angels; murders and acts of violence.”

This description could very well apply to Fuseli himself and his penchant for drawing the macabre: an old man watching a young girl imprisoned with a skeleton, a beautiful woman arranging her hair as the executioner, with his axe at the ready, look on, an incubus squatting on a sleeping girl’s chest while a nightmare sticks her fell head through the bed curtains.

“Although each of these images was, as Lessing had argued, “frozen” in its moment of time, the gallery “represents actions by placing bodies one beside the other in space” into “a proto-cinematic sequence” . Viewers, moreover, were prepared for this kind of visual experience by such inventions as the magic lantern (which projected painted pictures on a wall); the eidophusikon (which made such projections move and, in 1800, was advertised on the same page of the Monthly Mirror as Fuseli’s Milton Gallery); and the panorama (which moved viewers’ gaze around a continuous 360-degree image). Isaac Newton’s Opticks and other Enlightenment research, moreover, had demonstrated that an image persisting in a viewer’s memory could combine with a subsequent image to create the effect of motion. And Hazlitt, taking issue with Locke, described perception itself as a gallery of pictures, actively arranged and interpreted by the spectator. In sum, Calè suggests, spectators took a collaborative role in the production of public art and the literary canon: “Visual narrative is not ready-made, but assembled in the mind of the perceiver” . ( Luisa Cale )

"We can further argue that the macabre images in these paintings were meant to publicly express a variety of psychological fears and social anxieties surrounding taboo topics such as death, disease, and oppression. In this regard, these masterpieces are strikingly similar to horror films, presenting a similar iconography and playing a comparable cultural function. Thus, it is interesting to observe that the conservative segments of our society condone horror in highbrow art museums where it will be appreciated by the social elite, but deplore it if it is shown in movie theaters for their popular consumption. In any event it is impossible to ignore or obviate the influence of these artists to horror cinema. And as such, perhaps we should rightfully consider Brueghel, Bosch, Fuseli, Munch, Goya, Dore, Rembrandt, and Dali, as vital forgers of horror culture."

a

a

COMMENTS

COMMENTS