When Adolf Hitler left provincial Linz in late adolescence there was only one place to go: Habsburg Vienna, the great imperial city, home to a veritable Babylon of peoples, the ineffable seat of an ancient empire. But the crowded streets of Vienna through which he wandered as a destitute and sometimes starving young artist manque were dark with shadows of change and threat. A sad twilight was settling over the imperial city, even as its population, swelled by migrants from across the empire, was expanding exponentially.

But this is the point that Schnitzler is making: that fin-de-siecle Vienna is a city of illusions haunted by the implacable shadow of death.Schnitzler's secret is that his framework is artificial, but his people are real.

Hitler arrived in Vienna in 1907, leaving for Munich in 1913, a period when the labyrinthine Austro-Hungarian empire was inexorably unravelling, its disparate peoples inflamed by incipient nationalism. Everyone, it seemed, was in revolt against the long-nurtured assimilationist, multinational ideals of Franz Joseph, emperor of Austria since 1848 and king of Hungary since 1867. So by moving from Linz to Vienna, Hitler found himself adrift in what Karl Kraus called, in a phrase not mentioned here, “the research laboratory for world destruction”.

This laboratory in the last days of imperial Vienna included a great deal of what could be termed toxic and combustible. A strange and joyless sexuality was in the air. Appearing at every level of society, it was a form of excess and indulgence only one step removed from the Vienna love of pastry. Sensuality, for example was the theme of Arthur Schnitzler’s plays, which almost perfectly capture the decadence of the city. “Liebelei, Anatol, Reigen, Komtesse, Mizzi”: they were all variations on a theme, evoking a twilight atmosphere of autumn evenings and concerned with gay and useless love affairs.

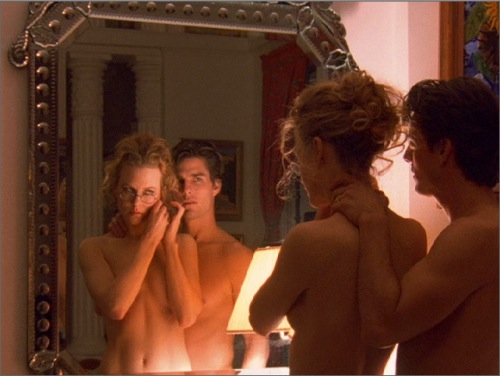

Kubrick turned to a property he’d acquired over twenty years previous: Traumnovelle (Dream Novella), published in 1926 from Austrian physician turned author Arthur Schnitzler. In the summer of 1994, Kubrick contacted screenwriter Frederic Raphael, who’d won an Oscar for his original screenplay Darling (1965) and written Two For the Road (1967). Updating the tale of jealousy and sexual obsession from turn of the century Vienna to modern day New York, Raphael was instructed to keep Schnitzler’s century old narrative.

“Reigen” , though written in 1900 , was not fully stage until twenty years later, because of its frankness. We know it better as “La Ronde” , the “ring dance.” The play is a series of ten scenes , each concerned with a momentary sexual encounter after which one of the partners moves onto the next scene. Beginning with a soldier and a prostitute making love under a Danube bridge, the action proceeds to more elegant trysting places- a restaurant’s private dining room, a country inn, the bedroom of a famous actress- and concludes with the actresses’s aristocratic lover waking up in the shabby bedroom of the prostitute who had entertained the soldier under the Danube bridge. In Schnitzler’s vision strong undercurrents of despair and futility run beneath the romantic and glamorous surface of life in the enchanted city.

"But Analyst Kupper suggests a question: If Poet Schnitzler was really a psychologist, was Psychologist Freud perhaps really a poet? For a long time before Freud, the soul had belonged in the domain of poets more than of physicians, who had increasingly concerned themselves with the physical being. Freud tried to subject the intangibles of the soul to the discipline of scientific materialism and determinism. And yet his insights may have been closer to the truths of poetry than to the truths of science."

It is perhaps no coincidence that Krafft-Ebing, the pioneer student of sexual problems, held the chair of psychiatry at the University of Vienna medical school. The atmosphere of despair and futility sensed by Schnitzler affected all levels of society. And it marked one of the more sensational episodes of the Hapsburg monarchy: the suicide of Crown Prince Rudolf. The grim little tragedy of Franz Josef’s only son was quite as debonair, as sexual, and as melancholy as the darkest of Schnitzler’s plays.

Sometime during the night of Jan 29,1889, Rudolf shot and killed first his seventeen year old mistress, the Baroness Maria von Vetsera, and then himself, in the bedroom of his hunting lodge at Mayerling near Vienna. At first glance the episode- except for its unhappy conclusion- had all the ingredients of one of Lehar’s musicals. There was a handsome prince and a lovely baroness. The affair was carried on at the highest level of society against an appealing background of walttzes and uniforms and wild Hungarian music. As a final touch there was the picturesque hunting lodge , deep in the Vienna Woods, where the couple met for the last time. It was all very sad, and intensely romantic, that the two young people had died for love. The legend of Mayerling is easy enough to understand.

"No one will ever really know what happened at Mayerling. What is known for sure is that, unlike in the film where there are two shots fired one right after the other, in actuality Mary was shot first and Rudolf didn't take his own life until 7 or 8 hours later. Mary was shot during the night and in the morning, Rudolf actually spoke to his valet about breakfast. He was even heard to be whistling before he died. In actual fact, after shooting Mary, Rudolf fell prone to second thoughts, and it was not until after a night of heavy drinking that he eventually shot himself the next morning. One of his letters of goodbye intimated that he no longer wanted to, but was left with no choice, as he had now become a murderer. "

But the affair, like the society in which it took place, was charming only on the surface. It was more than sordid, and it contained deep undertones of mental illness. Those concerned with the tragedy when it was first discovered sensed this, and some attempt was made to obscure the truth. The girl’s body, now fully dressed and set upright between her two uncles, was taken away in a carriage. After

rantic ride through the rain, they hastily buried her in the old abbey of Heiligenkreuz.The motivation for Rudolf’s act had very little to do with love, or with Marie Vetsera. It surely had something to do with sex, and it had more to do with his own curious personality. Rudolf was a strange, tormented, insecure young man, unhappy in his role as heir apparent to the Hapsburg throne. Unlike his father, he was an intellectual who found himself caught between two worlds. One one level he lived out the gay charade of imperial Vienna, running wild with bohemians and young aristocrats and, like Schnitzler’s Anatol, moving from one sexual conquest to the next.

Charlotte MacMillan:The ballet concentrates on Rudolf’s magnetism for women, for passing court mistresses, ambitious social climbers and his despised young bride, the sexual pathway to his almost satanic, morphine-crazed end at 31 with a 17-year-old girl whom he murders before killing himself. The scenario, which could be seen as a modern take on the lost Prince Siegfried in Swan Lake, is focused on his psychological trajectory, almost cinematic. MacMillan shows Rudolf’s fall via a series of remarkable and often upsetting scenes, contrasting parallel relationships of real and false love. Rudolf’s repulsion by his aloof, disturbed mother, the Empress, is countered by the feverish affection for him of her lady-in-waiting, Countess Larisch. His abusive treatment of women is resisted in vain by his young wife, Princess Stephanie, but embraced by the more masochistic Mary Vetsera, whose motives remain mysterious (and history indicates she may not have been as willing a participant in the pact as legend has it). There are other dual relationships in this world of emotional doubletalk - the Emperor is cold to his elegant Empress, and loves an older, more matronly opera singer, whose position the Court must politely accept. Vetsera herself, while apparently no more than an immature sensation-seeker with her claws in a prince, may be the victim of her own needy delusion that she too has a mother figure in Countess Larisch.

On another level however, the young man was searching for some way to justify his meaningless existence. He associated with Viennese progressives and mixed in the intricacies of Hungarian politics, showing in numerous ways his dissatisfaction with the reactionary tendencies of his father’s government. One day, in fact, he wrote an indiscreet letter to a friend who was editor of “Neue Wiener Tagblatt”. The letter contained a remarkable preview of the future. “A great and powerful reaction must come,” he wrote; “social upheavals from which, as after a long period of sickness, a wholly new Europe will rise and bloom.”

Gustav Klimt. Cowley:Political turmoil was paralleled by a different kind of turmoil in the arts. Artistic-intellectual fin-de-siecle Vienna was a world of radical innovation - the world of Freud, Mahler, Wittgenstein, Klimt, Schoenberg and the architect Adolf Loos. But this wasn't Hitler's Vienna, as Brigitte Hamann shows in her superb new study. Rather, Hitler's Vienna was a city of the "little" people, insurgent on all fronts, a city of the disadvantaged, of the hungry and homeless, of poverty, isolation and threat. The people among whom Hitler mingled were bewildered by Viennese modernity, by the currents of nationalism rippling across the empire. They viewed the new modernist cultural order as "degenerate", too cosmopolitan and libertine, too "Jewish" - a dire symptom of fragmentation and decay.

The events at Mayerling did not grow out of love but out of desperation-and neurosis. That Sigmund Freud was the product of the Vienna of this period shows, as few things can, the uncertain mood of the times. In a letter written in 1892 Freud made a remark that might have applied to the tragedy at Mayerling: “No neurasthenia or analogous neurosis exists without a disturbance in the sexual function.”

"This is the second version of Arthur Schnitzler's scandalous 1897 play, La Ronde, to hit London this year. At the King's Head last month, Joe DiPietro's Fucking Men offered a daisy chain of sexual encounters among American gay men, while in this piece by Alexandra Wood the desultory couplings take place in contemporary London."

ADDENDUM:

During his lifetime, Schnitzler was renowned for the sexual frankness of his writing, which led his friends to describe him teasingly as “a pornographer”. Adolf Hitler cited his work as an example of “Jewish filth”.

The writer had started visiting prostitutes at the age of 16 and was a notorious ladies’ man, for several years keeping a log of every orgasm he achieved. But he was also famed for his outspoken attacks against anti-Semitism – the Cambridge archive contains correspondence from the Zionist founder, Theodor Herzl, who urged Schnitzler to move to Palestine and become “the leading playwright of the Jewish state”.

Although the playwright never met Sigmund Freud, the Viennese psychologist described Schnitzler as his “doppelgänger” and famously wrote in a letter to the author: “I have gained the impression that you have learnt through intuition – though actually as a result of sensitive introspection – everything that I have had to unearth by laborious work on other persons.”

"Freud plunged into psychology and self-analysis, declared himself dedicated forever to the scientific search for the "naked truth." Having lived ascetically before marriage, he lived monogamously thereafter. Schnitzler discovered what he called "fictional truth," had a series of well-publicized affairs with glamorous actresses, and feverishly wrote about a character named Anatol (a thinly disguised self-portrait) who was a gay yet morbid epicure, a dandy with a death wish who thought he had to die to be truly free. Through the turmoil of world war and revolution, Schnitzler wrote play after play (notably Der Reigen or La Ronde) in which the characters were driven by unconscious impulses and riven by unconscious conflicts."

Lorenzo Bellettini: To redress this imbalance, we can show how the influence of Freud’s Die Traumdeutung (1900), Studien über Hysterie (1903), and Vorlesungen zur Einführung in die Psychoanalyse (1917) contributed to the maturation of Schnitzler’s prose style. An analysis of Schnitzler’s narratives Frau Berta Garlan (1901), Frau Beate und ihr Sohn (1913), and Fräulein Else (1924) illustrates the chronological development in Schnitzler’s controversial reception of Freud, from his first attempts to apply Freud’s techniques to isolated sections of a narrative, to his later development of the use of symbols and their deployment within complex leitmotiv structures, and finally how it is precisely this leitmotiv structure which comes to dominate the narrative framework in an exemplary later narrative.

Freud’s Traumdeutung influenced Schnitzler, but not to the degree that some critics have ascribed to it. We know from his diaries that Schnitzler read the Traumdeutung early in 1900. Attempts to establish its impact on Schnitzler have pointed out that he admitted to have learnt to dream “präziser” after reading Freud . However, a closer inspection of Schnitzler’s now accessible Tagebücher reveals that the expression occurs in a late entry that refers not to the Traumdeutung, but to the Vorlesungen of 1917. Others have regarded a certain “Freudsche Manier” in Schnitzler’s diary entries on dreams as the unquestionable sign of an impact of the Traumdeutung. “Freudian manner” is in fact a vague appellation that refers to the events of the past day as the alleged sources of the dream images. This was certainly theorised by Freud as “Tagesrest,” or residue of the day, but it was no novelty in Schnitzler’s diaries. It was already detectable in some scattered pages from the Tagebücher before 1900, some dating from as far back as 1875 .

What proves Freud’s influence at this stage is the application of numerous mechanisms of the dreamwork. They have been meticulously analysed by Michaela Perlmann in her study of the representation of dreams in Schnitzler’s literary corpus. Perlmann shows that, after he read the Traumdeutung, the residue of the day no longer appears as a solitary presence in Schnitzler’s fiction. It is accompanied by other phenomena of the dream creation, such as condensation, displacement, and distortion . It is this complex of the mechanisms of the dreamwork — which includes the residue of the day but does not exhaust itself in it — that constitutes the true element of novelty in the first narrative analyzed.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS