What are westerns all about? As the gunsmoke clears from the main streets of those frontier towns, there is always a persistent political theme. …

Where is the best place to hide a leaf? asked G. K. Chesterton’s fictional detective, and he answered: in a forest, of course. Where is the best place to hide the popular understanding? In popular things of course. Its beautiful. That period of the arty and aesthetic Italian version of an American western drama. Applying the Antonioni and Fellini template to the Old West. The western details are accurate and vivid, almost surreal, yet an essential ingredient was missing. It was the Western town itself, that rude dusty, self governing community with its familiar cast of citizens: the barroom ruffians, the gambling-casino owners, the hapless good folk, the dance hall madam, each of them related in complex ways to all the others.

Tim Dirks:After World War II, John Ford returned to the western icons of his beloved Monument Valley and filmed his dark version of the OK Corral shootout (between the Earps and Clantons) in the stunning classic My Darling Clementine (1946) again with Henry Fonda (as Wyatt Earp) and with Victor Mature (as Doc Holliday). The film adaptation, written by Samuel G. Engel, Sam Hellman and Winston Miller, was based on the book Wyatt Earp, Frontier Marshal by Stuart N. Lake, and proved to be another western film milestone. (There were at least five other sound films with the same subject matter, Wyatt Earp in Tombstone, before Ford canonized the tale.)

Without that vigorous political community, the Italian Western fell apart. The actors’ motives seemed contrived, their actions mere antics, their characterizations oddly weightless or merely grotesque. Yet the omission is excusable and understandable. Americans have never been aware, either, that the familiar life of the Western, the indispensable ground of their action, and the force that animates their characters, derive from the political life of the Western town, a small autonomous republic somewhere in the “the territories” ; the boondocks.

Popular things do make good hiding places. What is hidden in the American Western was nothing less than the shared American understanding of politics, an understanding so deeply embedded in the Western that we are scarcely aware of its presence. More surprising still, that political understanding is complex, clear-eyes, and in many ways profound. Viewed as political drama, the simple minded Western is not so simple at all.

" Gunfight at the OK Corral depicts perhaps the Old West’s most famous gunfight, when Wyatt Earp and Doc Holliday battle the Clantons and Johnny Ringo back in Tombstone, Arizona in 1881. An all-star cast – one of the best ever for a Western - led by Burt Lancaster as Earp and Kirk Douglas as Holliday, this film has as much explosive drama and exciting gunplay as most fans could want, especially when, at the beginning of the movie, legendary bad guy Lee Van Cleef rides into town, oozing malevolence, until Holliday impales him with a knife. And the title gunfight which erupts at the climax is, of course, one of the best, though not historically accurate – but who gives a bucket of mule spit?"

One of the great engines of the Western plot , for example, is the quest for “law and order,” but it is a republican law and order, totally different from the dubious doctrines expounded by recent Republican administration and advocated by a predominantly fundamentalist right and mainstream Tea Party advocates. According to these constituencies , the source of lawlessness and licentiousness of the people, must be curbed by the government through lawless means if necessary. Not so in the Western view, although Western lawlessness itself is conventional enough.

“Almost all the great American Western movies are intensely political films within a distinctly American framework. In effect they all adopt in one way or another the mythological fiction that so fascinated political philosophers in the 17th and 18th centuries: the problem of the transition from a state of lawlessness, ruthless self-interest, and terrifying uncertainty, the “state of nature,” to a political order, the rule of law and the surrender of one’s right to decide everything in one’s own case.” ( Robert Pippin )

The signs are always the same. Rude , bullying ruffians stalk the streets as though they owned them, shoot up the town for the fun of it, and make unseemly advances to gentlewomen. The sheriff does nothing; he is a drunkard or a coward or politically paralyzed. The mayor of the town turns a blind aye. We soon find out the cause of all this. The town is in the clutches of a lawless regime. Sometimes it is a cabal headed by the mustachioed owner of the gambling casino. More often, the town boss is the local cattle baron who long ago seized control of the town just as the great landed magnates of medieval Italy seized control of Italy’s free communes. To the cattle baron of the Western, as to a medieval Visconti, a free community bordering one’s demesne is intolerable and must be brought to heel.

"High Plains Drifter opens as a lone man rides from within the high desert thermals, looking spectral and ominous, seemingly a spawn of the arid bleakness around him. This dust-blown drifter is Clint Eastwood, of course, playing a stranger who guns down three men and rapes a woman (who asks for it) almost as soon as he arrives in the town of Lago, Arizona. But the stranger is troubled; he has nightmares about being whipped to death by three men. Then, frightened by the imminent return of three convicts, the townspeople hire the stranger to protect them. Eastwood then paints the town red, changes its name to Hell and hires a dwarf, his only friend, as sheriff. At the end we find out that

stranger was in fact the ghost of Marshal Duncan, exacting revenge for his murder."The swaggering ruffian’s are the cattle baron’s hired hands; that is why they swagger. The sheriff is the cattle baron’s appointee; that is why he is conveniently a sot. The mayor is in his pocket; that is why he is corrupt. In the Western the true source of lawlessness and disorder is not the people’s licentiousness. it is the direct result of lawless rule , and it stems from usurpation. This is a profound political insight, deeper by far, for example, than modern day sociological cant about crime, bad housing and lack of health care.

“…The first important psychoanalytic book about the movies was published in 1950. High Noon did not appear until two years later. However, when Martha Wolfenstein and Nathan Leites described the “major plot configuration in American films,” they could almost have been anticipating the script of High Noon. “Winning is terrifically important and always possible though it may be a tough fight,” they said. According to Wolfenstein and Leities, “The conflict is not an internal one; it is not our own impulses which endanger us nor our own scruples that stand in our way.” Rather, they said, the conflict is an external one – “a particular situation” that requires a confrontation. “The hero is typically in a strange town where there are apt to be dangerous men and women of ambiguous character and where the forces of law and order are not to be relied on,” they said. “If he sizes up the situation correctly, if he does not go off half-cocked but is still able to beat the other fellow to the punch once he is sure who the enemy is, if he relies on no one but himself, if he demands sufficient virtue from the girl, he will emerge triumphant” (Wolfenstein and Leites)….

…This plot is a version of what Jungian psychoanalysts call the “hero myth.” For example, Harry Wilmer, who has studied the nightmares of veterans of the Vietnam war, notes that a distinctively American variation on the theme of the hero myth is “the good guy-bad guy westerns with the shoot-out between the sheriff and the lawbreakers” . …Although my client happened to exaggerate the number of times that President Clinton had watched High Noon in the White House, he accurately characterized how much the movie had impressed Clinton. President Clinton says in his autobiography that in the early 1950s in his hometown of Hope, Arkansas, he could go to the movies “for a dime: a nickel to get in, nickel for a Coke,” and see “a feature film, a cartoon, a serial, and newsreel.” He says that among the many movies he saw he “especially liked the westerns.”

His favorite movie was High Noon: “I probably saw it half a dozen times during its run in Hope, and have seen it more than a dozen times since. It’s still my favorite movie, because it’s not your typical western. I loved the movie because from start to finish Gary Cooper is scared to death but does the right thing anyway” (Clinton ). The image of Gary Cooper had continued to serve President Clinton as a source of inspiration. “Over the long years since I first saw High Noon, when I faced my own showdowns, I often thought of the look in Gary Cooper’s eyes as he stares into the face of almost certain defeat, and how he keeps walking through his fears toward his duty,” he said. “It works pretty well in real life too” (Clinton ).”…

However, like everything else that is profound in the Western , it appears merely as a device of the plot, as a truth so widely shared by the audience it is taken simply as the way things are. It says much for the American republic and its capacity to generate a truly republican culture that one of its iconic art forms employs a complex political doctrine to set an adventure story in motion.

The doctrine might be called American populism, but there is nothing sentimental about it. Western movies never assume that rulers are inherently evil or people inherently good. The good folk, the church going folk of the Western’s polis , are emphatically not repositories of virtue. They attend citizens’ meetings at the church and wring their hands in dismay, but they cannot rid themselves of the incubus of the usurper.

They cannot bring themselves to act in concert against the local tyrant. Yet they cannot accept servility either, for they are free men. So they are merely unhappy. It is public unhappiness they suffer; unhappiness born of the unhappy state of public affairs. The point is an important one. In the Western, man is, in truth, a “political animal” in the Aristotelean sense. His life is a public life whether he likes it or not.

There is nothing arbitrary about the impotence of the good folk of the town. Their haplessness embodies a profound and rather bleak political truth. Machiavelli, in his “Discourse on Livy” , insisted that a truly corrupted republic cannot save itself by its own exertions. There is simply not enough civic virtue left in such a republic to restore the reign of civic virtue. As usual in the Western, this truth is embedded in the plot. It prepares a hero,s role for the hero of the action.

The corollary that Machiavelli drew from his bleak rule is that corrupted republics must be saved by outsiders. The Western reaches the same conclusion. An outsider comes to town. He is so much the ruffian himself, so obviously intimate with the dance-hall madam, that he repels the good people of the town- moral righteousness is their weakness as well as their strength. Gradually however, it dawns on someone that this brave, resourceful stranger might be the town’s salvation. Sometimes it is the drunken sheriff, his dishonor grown unsupportable, who deputizes the stranger and bids him uphold the law. Sometimes it is a few of the good folk who swallow their pride and beg the stranger for help.

The outsider agrees to clean up the town, but he does so reluctantly, for he is not a man of civic virtue. He has courage in abundance but no public spirit whatever. The reason he consents to help them is an exclusively private one. The town,s rulers long ago killed his father, or stole his ranch, or framed his brother. He will then topple them from power, shoot them like dogs, to avenge that private wrong. If it helps the townsfolk, well and good. His personal motives and their public motives simply happen to coincide.

ADDENDUM:

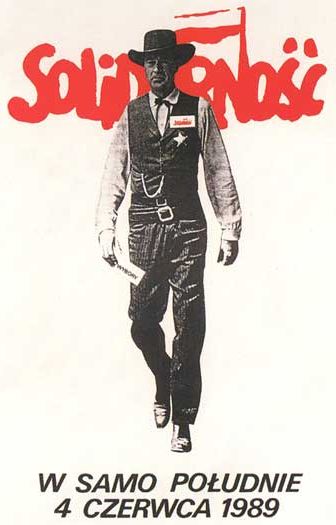

My client mentioned that he had on the wall in his office at work a six-foot poster of Gary Cooper in the movie High Noon. He described the poster as follows:

It’s a 1989 poster from the Solidarity labor movement in Poland. The image is of Gary Cooper walking. Above the image, it says “Solidarity” in Polish. Below the image it says, “High Noon” and the date. The date is the occasion of the first free elections in Central and Eastern Europe after World War II. Instead of a gun, Gary Cooper holds a ballot. And above his sheriff’s badge is a Solidarity button.

---My client said: "When I first saw the poster, I was amazed that the Poles had used that image on election day, that everyone in Poland would get the message, and that somehow democracy in Poland was tied to that image of America." He continued: "A Polish friend of mine said that High Noon is the great American foreign policy movie. It's the image of Americans as reluctant heroes: 'We didn't want to do it, but we had to do the right thing.' In the end, the Americans will come through for you." The opinion that High Noon is the great American foreign policy movie was first expressed by a movie critic half a century ago, in 1955, during the Cold War." I see 'High Noon' as having an urgent political message," Harry Schein said. "The little community seems to be crippled with fear before the approaching villains; seems to be timid, neutral and half-hearted, like the United Nations before the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea; moral courage is apparent only in the very American sheriff." The sheriff "wants to have peace and quiet," Schein said, but, however reluctant, he is a hero for whom "duty and the sense of justice come first, in spite of the fact that he must suddenly stand completely alone." According to Schein, "'High Noon,' artistically, is the most convincing and, likewise, certainly the most honest explanation of American foreign policy"---

The poster, by graphic designer Tomasz Sarnecki, is the most famous political poster in Poland. This is what Lech Walesa, leader of the Solidarity labor movement, winner of the 1983 Nobel Peace Prize, and president of Poland from 1990 to 1995, had to say about the poster:

I have often been asked in the United States to sign the poster that many Americans consider very significant. Prepared for the first almost-free parliamentary elections in Poland in 1989, the poster shows Gary Cooper as the lonely sheriff in the American Western “High Noon.” Under the headline “At High Noon” runs the red Solidarity banner and the date – June 4, 1989 – of the poll. It was a simple but effective gimmick that, at the time, was misunderstood by the Communists. They, in fact, tried to ridicule the freedom movement in Poland as an invention of the “Wild” West, especially the U.S.

But the poster had the opposite impact: Cowboys in Western clothes had become a powerful symbol for Poles. Cowboys fight for justice, fight against evil, and fight for freedom, both physical and spiritual. Solidarity trounced the Communists in that election, paving the way for a democratic government in Poland. It is always so touching when people bring this poster up to me to autograph it. They have cherished it for so many years and it has become the emblem of the battle that we all fought together. (Walesa June 11, 2004)

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Just brilliant. I admire and respect your intellectual ability.

Thanks. it was a good one! I much appreciate your comments; the additional things you bring to the subjects are very revealing of your own significant abilities. Best