Do we blow up the ranch and burn the town or just take it over and run it into the ground? There has been a tendency in the discipline of film studies to treat the Western as ideological and, hence, not to take individual films in the genre seriously. Alternatively, Westerns were taken to be disguised ways of discussing concerns contemporary to their makers, such as McCarthyism. However, there is a well grounded social and political philosophy found in at least the great Westerns that are deserving of study. In particular, the political philosophy on the question of legitimacy can be deeply problematic.

---The stylistic and atmospheric difference between a classic American western like Rio Bravo and the opening sequences of Corbucci's Eurowestern is just one instance of how European directors utilized classic gothic tropes and stylistic devices — in this case the trope of the darkly-clad mysterious solitary wanderer in a bleak desolate landscape — to challenge the dominant Hollywood myth of the American West.---

“All great works of literature contain variations and combinations, overt or implied, of such archetypal conflicts inherent in the condition of man, which first occur in the symbols of mythology, and are restated in the particular idiom of each culture and period. All literature, wrote Gerhart Hauptmann, is ‘the distant echo of the primitive world behind the veil of words'; and the action of a drama or novel is always the distant echo of some ancestral action behind the veil of the period’s costumes and conventions.” (Arthur Koestler, The Act of Creation, 1964)

William Wellman. The Ox Bow Incident. 1943. "Here Henry Fonda has his eyes blocked by the rim of a hat to recienforce the main theme of justice being blind."

Despair at high noon. In the dumps with Wyatt Earp. As the smoke drifted upwards and the ruffians were laid to rest on the frontier of the old west, there are some persistent political themes that have been acted out in the American and European versions of the western. Are they compatible, complementary or mutually exclusive platforms that wage ideological war on disparate and remote targets? Money and violence as a symbolic and aesthetic dimension assume differing importance within the context of the Eur0pean and American director’s sense of the privilege and freedom in using violence, and its connected symbolism with money and its relationship to hope and the greater community.

As well, much is knitted into a broader usage of Biblical themes; a Sergio Leone secular version of God and an American conception where God shapes the destiny of the people and is always the posse in waiting. In the Italian Westerns, God does not challenge the violent men ; he lets them sort their problems out on their own. This forms the ideological rationale as to why the Italian westerns are violent; God has left us already, so we can do whatever we want. Violence in the classic Hollywood western, is almost a social necessity, a means toward a noble end, and when used in this light it represented “manly virtue” . The violence pictured between cowboys and Indians, the Cavalry and the Confederates, are all necessary struggles in the larger process of civilization that will ultimately lead to the realisation of a utopian community the settlers were destined to build in this new-found land.

Ultimately, the makers of Eurowesterns employed a cinematic technique sometimes referred to as “grotesque perspective” in order to subvert the often utopian and mostly nostalgic ideological point view of the classic American westerns of, for instance, John Ford or Howard Hawks; or at least put into question the conception of a positive utopianism and underlines the American narrative. But ultimately, there is a convergence based around the male characters relationship to the law: the law being ideals that reflect the deeply underlying structure of masculinity. When the law fails to be true to these masculine ideals, it exiles the one who seeks to uphold his own masculine understanding of the law, even before the exile is made actual.

"Hawks' Rio Bravo is a clear instance of an American western that takes its subject seriously, heroically, and ideologically affirmative. The film ends with two deputies having a private joke at the hero's (John Wayne's) expense, as they wonder about becoming sheriff one day. Their eyes are on the future, which, due to the intervention of the all-American hero, is bright indeed."

Psychoanalytically, the law also represents phallic underpinnings of masculine uprightness. The Leone films present a form of masculinity that goes against the traumatic undoings of the protagonist; a castrated masculinity where the use of sexual violence are at degrees that allow the stranger to maintain phallic power despite trauma seems to run against the underlying theme of traumatic undoing that is so graphically displayed. Its the ideals of a post-traumatic self and idealism that lingers in its very absence. Walter Benjamin has written that allegory is the retinue of destruction, but it can also be that allegory, in the sense that evil, defined as the annihilation of history and subjectivity for the victim can never be known directly: therefore we can approach it only through a series of signs that break up the very sources of meaning upon which we ordinarily rely to understand our world. It is not a traditional narrative since the pulsion is towards an evacuation of ideals.

="499" height="212" />

="499" height="212" />Once Upon a Time in the West. 1969.

In both the American and Eurowestern, it is typically the psychic survivors of trauma that lend the films their allegorical character and in Europe this often linked to the trauma of World War II and fascism which inform the psychic profile of the fearsome “no-self” characters:

“In this obfuscation of the truth, evil eludes accountability and justice. Secrecy, concealment, denial, ambiguity, confusion: these are Satan’s fellow travelers, requiring elaborate interpersonal and intra-psychic collusion between perpetrators and bystanders. The operations of silence potentiate evil and remove all impediments from its path.” ( Drucilla Cornell )

The Western is probably the defining genre of Hollywood filmmaking. Westerns generally take place in the post-Civil War era and raise a number of very important issues about the particualar nature of American society. Among them are the following: because they take place shortly after the Civil War, Westerns are concerned with the question of how to heal the wounds created by that devastating conflict. Because they take place in the American West, they must come to terms with the question of whether America’s westward expansion justified the forced eviction of the indigenous population. Finally, because the settlement of the West entailed the introduction of modern commercial society with its intricate system of law and order, Westerns deal with the question of what the effects of such a change are on the lived lives of human beings….

The American Western film is far from being optimistic. It emphatically denies what its critics so blandly assume; namely that a corrupt regime can be overthrown peacefully. If the Western movie’s political understanding is fallible, the error is exaggerated in a form of extreme pessimism, almost nihilistic, in its tacit assumption that only through violence and insurrection can free men rid themselves of entrenched corruption.

"The Ox-Bow Incident, a tragic, gut-wrenching tale starring Henry Fonda and directed by William Wellman, was produced as World War Two raged in 1943. The film is about a posse that turns vigilante and lynches three men for a murder that - as it turns out – has not been committed. Back in town, after finding that the three men were innocent, Major Tetley, the leader of the posse, dressed in the grey uniform of a Confederate officer, then promptly goes off and shoots himself. This parable of anarchic western justice was a critical success, though it didn’t make much money."

The Western genre, it is worth noting, was born after World War I in the aftermath of bitter defeat, the final defeat of what were once known as “Western ideas”: the People’s Party and its program, the Western progressive movement, the entire radical republican tradition. Threaded through hundreds of these Westerns are bitter traces of the old populist attitudes: hatred of banks and railroads, of greedy cattle barons and foreclosing landlords, and of all the smaller fry who served their interests.

In the Western the old republican spirit lives on in a kind of suspended animation. Its political understanding is passive, embalmed as mere plot. It is republicanism turned into ritual, for the classical Western is as rigid and ceremonial as a japanese Noh play. Nonetheless the Western does have enduring qualities. What keeps it alive is what lies embedded within it, what Americans still want to see affirmed: namely, their own political understanding, an understanding born of the experience of republican liberty and of the public corrupted.

Tim Dirks:Western films have also been called the horse opera, the oater (quickly-made, short western films which became as commonplace as oats for horses), or the cowboy picture. The western film genre has portrayed much about America's past, glorifying the past-fading values and aspirations of the mythical by-gone age of the West. Over time, westerns have been re-defined, re-invented and expanded, dismissed, re-discovered, and spoofed. In the late 60s and early 70s (and in subsequent years), 'revisionistic' Westerns that questioned the themes and elements of traditional/classic westerns appeared (such as Sam Peckinpah's The Wild Bunch (1969), Arthur Penn's Little Big Man (1970), Robert Altman's McCabe and Mrs. Miller (1971), and later Clint Eastwood's Unforgiven (1992)).

They want to see a community under the reign of corrupt rulers, to trace the consequences of their corruption, to watch them in the end toppled from power. That is a free man’s pleasure. They want to see the bright stage of an American polis where each life touches all lives, where each person’s actions affect the common fate, where everyone is a citizen and everybody matters. That is a free man’s ideal.

” ( Robert ) Pippin claims that the great Westerns make an essential contribution to political philosophy, specifically to our understanding of what he calls “political psychology,” by which he means the way in which human beings, with their complex structure of passion and desire, are suited or not to the political structures within which they find themselves. Indeed, he thinks that paying attention to what Westerns have to say about this can enrich what he takes to be the reductive focus on much contemporary political philosophy on the question of legitimacy, i.e., what justifies the state’s monopoly of coercive power.”

Often these films are clearly about the transition from a society where rugged individualists could prosper to the modern commercial society that demands different virtues of its leaders. But interestingly often the film’s ends by showing that the modern society has more of the traditional society within it than it cares to admit, thus making the transition less of a radical break than its proponents would acknowledge.

----The above visual elements suggest that the content and philosophy of A Fistful of Dollars can be read in neo-realist terms. The main similarity is that in both cases the characters are trapped by their lives. Leone in Frayling (2006, p.131) says that his characters are inspired by the characters of Sicilian theatre because they are “working within a fairly restricted margin.” However, the representation of ‘being trapped’ differs in westerns and neo-realist films. In the latter, the characters initially do their best to change the situation, but to no avail; they barely survive. On the other hand, in Italian westerns the environmental conditions of the characters are so cruel and unpleasant that they cannot expect any form of survival. They either succeed entirely, or lose it all. It is due to the above doctrine that ‘money’ is so important in these films. According to Frayling (2006) and Cooke (2007), if in the case of American westerns money is a tool or way for reaching a higher goal (a woman’s love, helping others, escaping a hard life), in Italian westerns it is the ultimate objective. Frayling (2006, p.51) explains this idea as such: “The ‘hero’ does not spend his dollars: he treats them strictly as ‘prize’, as ‘something that must be grabbed before the next man reaches them.’ ”----

The narrative structure of ” The man Who Shot Liberty Valance” enables it to present a clear contrast between the modern, commercial world of Shinbone, where its framing story takes place, and the older, wilder world that it has replaced. In so doing, the film is able to take a critical stance in regard to the bringing of law and order to the West. What superficially might be taken for progress and modernization is presented in the film as coming at the cost of a diminution in the character of the men who inhabit the modernized West. This is nowhere clearer than in the film’s contrast between Dutton Peabody (Edmund O’Brien), the crusading editor of the “Shinbone Star”, who is willing to risk his life in order to expose the villainy of the ranchers and their henchman, Liberty Valance — and Maxwell Scott (Carleton Young), Peabody’s successor. Faced with a tale that reveals that the legal structure of Shinbone is founded on a lie and a crime, Scott blithely replies, “This is the West, sir. When the legend becomes fact, print the legend.”

“Liberty Valance” is less a film that provides us with a mythic account of the founding of Shinbone as a modern, commercial society than it is a commentary on such foundational myths, and how to rationalize the actions as legitimate and justified. What the film shows is that such mythological accounts render invisible the real sacrifices that individuals made to allow the regulated world of law and order to prosper. This is because the acts that are necessary to create that world actually violate its norms and hence must be covered in myths.

Italian director Sergio Leone brought many profound changes with his trio of low-budget "spaghetti" western films made in Europe (Spain and Italy) in the mid-60s, but not released in the US until 1967. The changes were a new European, larger-than-life visual style, a harsher, more violent depiction of frontier life, haunting music from Ennio Morricone, choreographed gunfights, wide-screen closeups, and TV's Rawhide (Rowdy Yates) star Clint Eastwood as the mysterious, detached, amoral, fearless and cynical gunfighter (dusty, serape-clad, stubbly-faced, and cigar-chewing) and bounty hunter - 'The Man With No Name.'

Most of the early Spaghetti Westerns, such as the early works of Sergio Leone and Sergio Corbucci, dealt with some subtle political themes, particularly a criticism of Western capitalism and the “dollars” culture of America; however, as a general rule they were secondary to the main plot of the films in question during the early stage of the genre’s development in the mid-’60s. Leone’s “Fistful of Dollars” set a standard; he designed a roadmap for a violently nihilistic cinematic style that dramatically separates Euro westerns from the Hollywood variety through a deconstruction, an unpacking of the docu-drama elements and pushing the radical form of republicanism found to propel a violent political narrative. Hence, in the late ’60s the Spaghetti Westerns were political allegories, often using the Western setting to mask,to an extent, the intended political outlook, in order to make them more palatable.

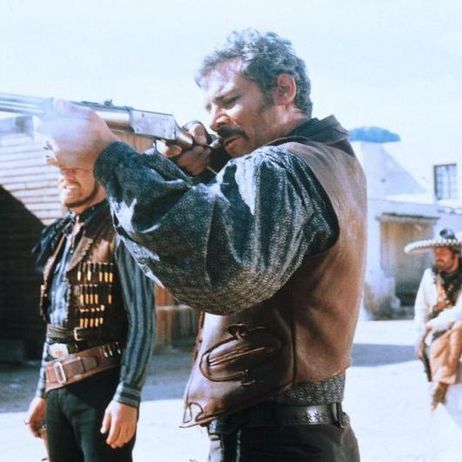

---...Leone portrays his antagonist, Ramón (Gian Maria Volonté), in A Fistful of Dollars. Prior to Ramón’s first appearance in the film, Joe (and hence the spectators) learns from the film’s characters that Ramón is an artist with a gun; and that he shows little mercy towards others. Tension is built leading up to Ramón’s introduction at approximately twenty-five minutes. The audience wonders: “is he really that good with guns?” “is he really a vicious man?” Using violence in a symbolic manner not only bypasses the generic codes of the Italian western, but destroys the suspense generated around the antagonist. Leone cleverly avoids any symbolic attempt at the antagonist’s portrayal. Therefore, the first time that the audience encounters Ramón is when he is behind an automatic machine gun slaughtering a whole platoon. Furthermore, his great marksmanship is demonstrated when a wounded soldier tries to escape and Ramón shoots him dead with his Winchester rifle at distance. In Italian westerns characters are privileged with an absolute freedom to use violence.---

Although Italian westerns are popular films, they are nevertheless affected by some of the conventions of a less popular group of films, Italian neo-realism. This is not to say that the Italian westerns are pure artistic pictures which try to manifest the socio-political issues of their day and rekindle the consciousness its people. On the contrary, these films were entertainment vehicles aimed at providing audiences with a break from the reality of everyday life.

The first aspect that recalls neo-realism is the use of (on-location) sets. In the opening minutes of “A Fistful of Dollars” the audience observes the man with no name, Joe (Clint Eastwood), entering the border town of Saint Miguel (shot in the desert regions of Almeria, Spain). The town, although populated, is depicted as a ghost town. The emptiness of the streets portrays the total lack of all concepts that make relations between humans dynamic: love, respect, humility, sacrifice, understanding and above all, law. The sets contribute immensely to this portrayal by being simple and white, like the pale face of the dead person who rides horse back into the town. It can also be said that this whiteness is a façade concealing the dark side of a town destroyed and corrupted as the result of gang wars.

"One of the first popular political Westerns, still highly regarded as one of the genre's best, was Sergio Sollima's 1966 film "The Big Gundown", with Lee Van Cleef and Tomas Milian. The original screenplay had originally involved an Italian police detective, ordered to chase down a Communist revolutionary accused of raping and killing an industrialist's wife, only to find that the revolutionary had been framed by the industrialist - but he kills the revolutionary anyway. Sollima took the story line, transplanted it to 1880's Colorado, and changed the film's ending to a considerably happier one."

In addition to the sets, the realistic make-up of the characters is also borrowed from neo-realist cinema. In both cases, the make-up is not solely an artistic attempt to present a character’s appearance, but a medium for encoding a message that goes beyond character: the unshaven, dirty and sunburnt faces of the characters illustrating the brutal environment which envelops them. The critic Christopher Frayling explains the source of this realistic view by writing: “Leone often bases his characters’ appearance on nineteenth century photographs.” Joe is a handsome man, but this beauty is distorted by the make-up. In contrast to this, in the American westerns of John Ford or Howard Hawks, no matter how unfavourable the situation, the characters still have time for a shave and bath –that is, they look tidy and clean. This smartness represents the idealistic nature of a strong and tough American subject; Americans like to see their heroes well-groomed.

The representation of violence in Italian westerns differs fundamentally from the American westerns. The re-conceptualisation of violence in the former is a reflection of violence in the Italian society of the 1960s through terrorist political activity. Lino Micciché cited in Frayling explores this notion by writing: “the Italian Westerner … is a commonplace of the everyday psyche of the ‘average’ Italian who has the urge to overwhelm … in order not to be overwhelmed, the urge to guarantee that you will not become anyone’s victim.” This everydayness of violence is the first level of difference from Hollywood films. In the latter, a community and/or a person seeks peace. The obstacle to peace arises from the usage of violence by others. However, in Italian westerns the protagonist or the community has another approach. They utilise violence not for defending themselves, but for avoiding being violated. Whereas in Hollywood films the proper etiquette is to calm the situation, in Italian films the protagonist aims to provoke violence as much as possible. Joe proves this notion in the first fifteen minutes of “A Fistful of Dollars” by murdering four people because they make fun of his mule.

ADDENDUM: Sergio Leone-

The trio of films that demythologized the Old West actually resulted in a revival of the genre in the mid-to-late 1960s:

A Fistful of Dollars (1964), with a plot borrowed from Akira Kurosawa’s samurai warrior classic Yojimbo (1961) and from Dashiell Hammett’s crime novel Red Harvest; the film inspired Walter Hill’s gangster film remake Last Man Standing (1996) starring Bruce Willis

For a Few Dollars More (1965)

The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly (1966) – the best and most ambitious film in the trilogy – the story of a quest for a cache of hidden Confederate gold by three uneasily allied, gritty characters: Clint Eastwood (the good), Lee Van Cleef (the bad), and Eli Wallach (the ugly)

The director’s true western epic masterpiece was Once Upon a Time in the West (1969), filmed in John Ford’s favored location, Monument Valley. It starred American icon-actor Henry Fonda as its black, villainous murderer, and brought together all the themes, characterizations, and experimental visuals from his previous three films. The only other film that featured Henry Fonda in a rare villainous role was in Vincent McEveety’s Firecreek (1968).

COMMENTS

COMMENTS

Dave, loved the Western genre and still do. Back then, Django was For Adults Only. Then the notch was lowered to rated R. I would have enjoyed them as a kid when adults around you talked of the frenzy of escapades and confrontation.

A whole set of frames was ablazed with the scene “TECHNICOLOR.”

It was the big thing; though I am a big black and white fan. Writing about them and “unpacking the documentary ” style does make one understand what was so compelling about them.