His is the simple and yet incredible story of an unworldly petit bourgeois who painted in an introverted, almost autistic manner. He himself cannot have been fully aware of what he was doing; he did not distinguish between his pictures and reality, and in art as in life remained gullible to the end. It is clear that, as he ceaselessly attracted public attention, such eccentrics of the fin de siècle as Alfred Jarry, Paul Gauguin and Guillaume Apollinaire saw him as a kind of talisman and living proof of the ideas with which they sought to combat bourgeois ignorance and blinkered values.

It is no less clear that Rousseau played along with the intellectuals’ game, as his first biographer, the German art critic and collector Wilhelm Uhde, surmised in 1911 and the historian Henry Certigny confirmed fifty years later; he shaped his own naive persona partly in self-defence and partly to gam the recognition he craved….

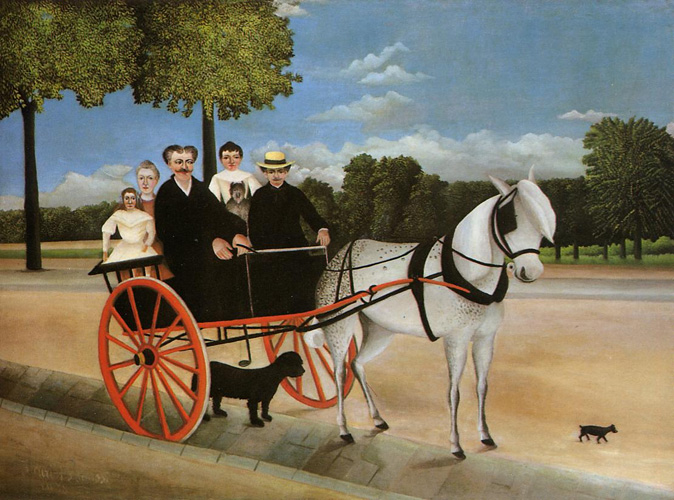

"An anecdote concerning the group picture, The Cart of Pere Juniet, demonstrates Rousseau's characteristic attitude. The American painter Max Weber, pupil of Henri Matisse, pointed out to the Douanier that the dog underneath the cart was so large as to be out of all proportion. Rousseau's answer, "Because it has to be that way", is not in the least naive. Comparison with the photographs from which he worked show that each motif was thought out, as a formal element of composition. The tree appearing behind the group is emphasised as an axis repeated in the proudly seated figures. An additional person fills the gap behind the owner of the cart. The piece of -wood blocking the horse in the photo disappears. The dog with its black silhouette offsets the precariousness of the cart, and even the disproportionately tiny puppy finds its counterpart in the crotchet-shaped pedal. Everything, except the black-white-red contrast in front of green, yellow ochre and blue, has its place in the scheme of balance. In this incidental picture, which, like Pop Art, constructs "reality at second hand", one motif is particularly striking: presumably with the pantograph, Rousseau copies the wheel with its spokes in "correct" perspective. This hyperrealistic item disturbs the tapestry-like quality of the picture. It is at this point that magic takes over, The consistent two-dimensionality of the scene triumphs over conventional perception, transforms the one remainin piece of everyday reality into something strange."

His exotic paintings of tigers and lions prowling in a lush, colourful jungle are among the art world’s most familiar images: extraordinary images of hothouse plantations inhabited by exotic creatures; images in which every single element is depicted with precision, sumptuous colour and claustrophobic intensity. They are dream images of impossible places and very far from the suburban reality of Rousseau’s everyday life. The paintings are indeed extraordinary works of imagination. Rousseau worked as a lowly customs official after moving to Paris in 1870 and his dreamlike visions were inspired by postcards, films and his imagination rather than first-hand experience.

---In 1909 the art critic Arsene Alexandre wrote in the journal "Comoedia": "With will alone the good Douanier Rousseau could not have done it. If this touching allegory had been intended, if these forms and colours had been derived from a coolly calculated system, he would be the most dangerous of men, whereas he is surely the most honest and upright..." These words remain an apt indication of the fascination exerted by an artist who by following his natural disposition "naively" achieved intuitive compositions that an artist given to theory could have achieved only by means of great labour, having first to escape the trammels of rational thought.---

Rousseau’s tightrope walk between optical impression and visionary outcome explains why both traditionalists and avant-garde agreed, albeit for different reasons, on the label “naive” for the creator of this magical other world. Both used the picture in their reflections on what was possible in the realm of painting, and on the historical development of aesthetic theory. In the face of such theorising it is indeed tempting, the path of least resistance, to stylize Rousseau as the embodiment of the grass-roots artist unencumbered by cultural baggage, much in line with the line of thought of Jean Jacques Rousseau; the artist as noble savage.

Rousseau’s interest is always directed immediately and impartially to the object before him. Method, style, his own distinctive mark are subordinated to his perceptions. His concern is with precision, with the meaningfulness of detail rightly observed.

Since he was no master of linear perspective, and yet desired to convey the familiar illusion of space, the objects painted invariably undergo an involuntary planar transformation. Intuitively the Douanier ceases to “open a window on reality” and paints his way into the tradition of surface and segment. Camille Pissarro, who with Odilon Redon was one of the first to admire the artist, attached great value to this spontaneous creativity, which, in his opinion, replaced studied technique by true feeling.

A primitive could not have painted most of Henri Rousseau’s paintings. This is particularly true of the exotic and tropical scenes that preoccupied much of the last five or six years of his life. They are huge, mural-sized canvases- some up to 10 1/2 feet wide- that have an awesome strangeness. A lion devours a leopard headfirst; a group of monkeys upset a bottle of milk-why? Where did they get the bottle in the first place? A snake festooned African woman plays a flute. But the central incident is at all times enveloped by the backdrop of the jungle, with its complicated tracery of leaves and branches, its rare birds and its great lotus-like flowers, its cascades of oranges.

Stabenow:Nothing is just itself. Cool blue-green transforms the piles of cargo veiled in tarpaulin into a gleaming moonscape of strange transparency. The piers of the bridge hover over the seemingly frozen river without supporting the structure above them. The lights reflected in the water take on an existence of their own, independent of the bright gas-lamps to which, by rights, they belong. The ships' masts with their little tricolor pennants reach upwards into the clear evening sky, in harmony with the Paris rooftops, chimneys and towers, but without spatial reference to the bridge. Liberated from the everyday bustle which Emile Zola's hero Claude Lantier experienced at this very spot, the metropolis becomes a picture of peace. Into this still life, the little exciseman Rousseau paints himself centre-stage, on the borders of day and night, of outer and inner reality, dreaming and keeping watch over his idea of beauty.

There is an eerie stillness about it all; the orange sun or the white moon is timeless; the owls or the apes peer out through the branches with quizzical unconcern. These creatures, are,Roger Shattuck writes, “semi-legendary dream figures, animals, and aboriginals. For Rousseau, landscape is not houses or mountains or virgin forest; it is man walking in wonder among the trees.” The Tropics of the Mind, then: but this is more than just the stuff of dreams. It is almost as if the Douanier had touched on some immemorial language

myth, had by accident reached back into the forgotten memories of an ancestral darkness.Art historians have managed to account for a good many of the sources for the Douanier’s jungles. Evidently he was inspired by the exotic exhibits of the Paris World’s Fair of 1899, including the “native villages” clustered around the base of the fair’s 984-foot centerpiece, the Eiffel Tower. He constantly visited the great glass conservatory of the Jardin des Plantes; and, indeed, the nature of his jungles- with their implausible juxtapositions of ornamental flora from all over the world and their careful placing of scrap-shaped reeds in the foreground, as at the edge of a walk- is the nature of the hothouse.

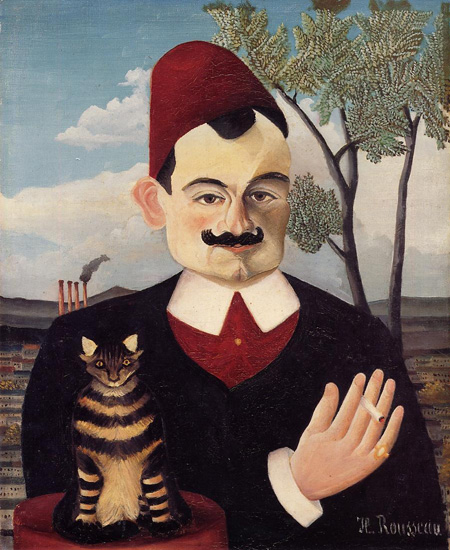

"In the exotic portraits with which Rousseau bids farewell to the petit bourgeois world, the form becomes even more radical. The head-and-shoulders portrait of a man dressed in oriental style, accompanied by his tabby cat with tiger stripes, sitting before an urban industrial landscape, was painted about 1905. It is not certain whether this portrays the popular writer and traveller Pierre Loti, or a certain Edmond Frank, journalist and poet of Montmartre, who in 1952 recognised himself in the picture. Be that as it may, Rousseau knew how to stage the eccentricities of the poet. The dandy with his cigarette would not be out of place beside the "islander" Gauguin or the magician Sar Peladan. Constructed like a playing-card in black, white, red and yellow ochre, the figure casts a spell over the melancholy sea of houses; in the spirit of Paul Verlaine he raises the song of the leaf from the ash of the city. The matching of colour shapes, the collage-style hand that echoes the chimneys, the ear flattened two-dimensionally and the face with its almost Cubist facets - all these features combine to give the work a rigour which is reminiscent of late Gothic painting, and a modernity not found again before Leger."

Rousseau made sketches at the Paris zoo. He took some of his subjects from engravings, from old magazines, and even from a child’s picture book of wild animals. But how he transformed them! The photograph of a zoo keeper playing with a jaguar becomes a painting of an African attacked in the jungle. And if we can give Rousseau credit for a little sophistication by this time, he shared with French intellectuals a traditional fascination with the ideal of the tropics- an ideal that, in his own day, played a part in the quests for the exotic and uncontaminated of Baudelaire in Africa and Gauguin in Tahiti.

But none of this really explains why Rousseau ( nicknamed the “Douanier” by Alfred Jarry ) painted his jungles. And why, too, he attached so little value to them. He seems to have regarded them lightly because they were the easiest paintings to paint; out of all the exotic landscapes he did between 1904 and 1910, he chose to exhibit only eight. They were, in every sense, his most “natural” works.

Portrait of Joseph Brummer. ..."Behind the casually elegant figure Rousseau painted a cryptic picture within the picture. It is the encoded signature of the proud inventor of the jungle landscapes and at the same time it celebrates the successful connoisseur and dealer who bought and sold not only Japanese woodcuts and African sculpture but also the works of the so-called primitive."

If he painted so many, it was because they sold well. Were they, as Wilhelm Uhde suggested, the ultimate excape from his own hardships and the depressing paris he knew: does this explain why he altered the “very scale of his work, replacing a small sized canvas with one that all but filled his little room”? Or why “Rousseau was sometimes so fevered by his conception that he would break off work and throw open a window for air”? Had he stumbled on some hidden part of himself that grew at once more terrifying and enthralling as it became more real? If we knew, we might have the key to the riddle of Rousseau.

To some degree, Rousseau jungle paintings seem to touch the name nerve that Graham Greene was examining in “The Heart of the Matter” ; the protagonist, Scobie, remains utterly honest in his deceit, and consistent in his unpredictability. His life becomes a beautiful, uncontrolled mess.

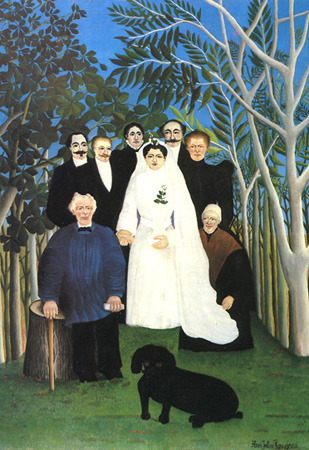

"Like a photographer, he arrests all movement and seizes the solemn moment. Rousseau does everything possible in order to achieve ceremony. He positions the wedding guests in front of chestnut trees and acacias which outdo the naturalistic trappings of the photographer's atelier, and achieves a kind of fantastic reality. By means of simple outlines and black-and-white contrast he gives the static group close cohesion. Problems of representation the painter overcomes by imbuing the figures with a magic quality: the man sitting down seems to become one with the tree-stump, and the bride defies gravity and hovers in the centre of the group; the hyperdimensional black dog becomes a kind of totem animal and at the same time provides the balance that the picture requires."

Henry Scobie is an Assistant Chief of Police in a British West African colony. It is wartime and he has been passed over for promotion. He is fifty-ish, wordly-wise, apparently pragmatic, a sheen that hides a deeply analytical conscience. Louise, his wife is somewhat unfocusedly unhappy with her lot. She is a devout Catholic and this provides her support, but the climate is getting to everyone. She leaves for a break that Scobie cannot really afford. He accepts debt.

His wife’s simple orthodox Catholicism contrasts with his never really adopted faith, or any faith. He tries to keep face, but cannot reconcile the facts of his life with the demands of his conscience. His ideals seem to have no place in a world where interests overrule principle. He sees a solution, a way out, but perhaps it is a dead end….

For twenty-first century sensibilities, the colonial era attitudes towards local people appear patronising at best. Perhaps that is how things were. But The Heart Of The Matter is not really a descriptive work. It is not about place and time. Like Rousseau’s paintings, and by extension, even a Shakespearean tragedy, the events and their setting provide only a backdrop and context for a deeply moving examination of motive and conscience. And also like a Shakespearean tragedy,and Rousseau’s Jungle paintings, Greene’s novel transcends any limitations of its setting to say something unquestionably universal about the human condition: a struggle between opposites and ambivalent coexistence between faith, evolution,intelligent design and some deep-rooted any quasi-mystical fermentations and ruminations of a bygone past anchored in some lost corner of consciousness as Scobie in some African backwater.

"And to Picasso, at the end of the soon-to-be-legendary Banquette Rousseau, he pronounced tearily, “You and I are the greatest painters of our time, you in the Egyptian style, I in the modern.” Onlookers sniggered at the audacity, but Le Douanier knew what they did not yet know, that his spirited jungle had been colonised by a race of people who walked sideways and spoke in hieroglyphics."

Interestingly, and perhaps revealingly, Rousseau’s work has been used in the treatment of children with Asperger syndrome and autistic spectrum behavior; and the apparent complementarity with Rousseau and the development of naturalistic and spatial intelligences among these children: Consider the curriculum design named “Rousseau’s Forest” in the unit “Colors and Shape” as an example. The instructors designed activities for problem Types II through IV. Problem Type II was to use shape and color features to distinguish different plants in Rousseau’s paintings. Problem Type III was to tell shapes and colors of common plants in ordinary life. Problem Type IV was to think outside the box and draw various kinds of plants, while another Type IV was to practice a color mixing exercise to draw green plants of different species. Scoring criteria from 1 to 5 were designed. In this course, the instructor introduced paintings of Henri Julien Félix Rousseau, a French Post-Impressionist painter. Preschoolers were encouraged to make creative paintings through cognitive learning and artistic stimuli in varied multimedia types… ( Elena L. Grigorenko, Yale )

"Many years later he would paint this celebratory tableau, “Liberty Inviting Artists to Take Part in the 22nd Exhibition of the Societe des Artistes Independants”, seen here. The glowing gates of a great hall open to rows of artists, most in black suits and with dark hair and beards, like him."

ADDENDUM:

A bit more on the Artist.Ranking (A.R) system mentioned in our Rousseau biography, as found at ArtFacts.net.

As mentioned, lonely old Henri is currently ranked #724 with a bullet on this overtly mercenary chart, which arranges 62,436 artists by volume of exhibitions over the last five years. Picasso is #1, Cezanne 32 and Monet 62, just to grab some examples.

“The basis of the A.R thinking is the so-called economy of attention (after a book from Georg Franck),” the website explains. “Franck says that attention (fame) in the cultural world is an economy that works with the same mechanisms as capitalism. Capitalist, or economic, behaviour is based on property, lending money and charging interest.

“For Franck, the curator (eg the museum director or the gallery owner) acts as a financial investor. The curator/investor lends their property (their exhibition space and their fame) to an artist from whom they expect a return on their investment in the form of more attention (reputation, fame etc).”

Here’s the top 10 after Picasso: Andy Warhol, Bruce Nauman, Gerhard Richter, Joseph Beuys, Paul Klee, Robert Rauschenberg, Henri Matisse, Edward Ruscha and Cindy Sherman.

Uncle Salvador comes in at #26, surprisingly six places behind Max Ernst. Other well-known names in the top 100 include Cézanne at 32, van Gogh at 45, David Hockney at 49, Jackson Pollock at 52, Degas at 54, Monet at 62, Damien Hirst at 70, Chagall at 71, Gauguin at 74, Magritte at 84, Christo and Jeanne-Claude at 89 and Edvard Munch at 94.

Exhibitions by Christo are that much in demand? Something to wrap your mind around.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS