Lady Mary Wortley Montagu prettily characterises Fielding and this capacity for happiness which he possessed, in a little notice of his death when she compares him to Steele, who was as improvident and as happy as he was, and says that both should have gone on living forever. One can fancy the eagerness and gusto with which a man of Fielding’s frame, with his vast health and robust appetite, his ardent spirits, his joyful humour, and his keen and healthy relish for life, must have seized and drunk that cup of pleasure which the town offered to him….The young man’s wit and manners made him friends everywhere: he lived with the grand Man’s society of those days; he was courted by peers and men of wealth and fashion. ( Thackeray )

" Putting the Progresses into a broader perspective, Belgian theorist Thierry Smolderen emphasises the subsequent significance of Hogarth’s ‘arabesque’ digressions, adopted by such contemporary novelists as Laurence Sterne and Henry Fielding, and his invention of a ‘polygraphic language of irony and humour, capable of conveying the complexity, tensions and contradictions of the times’ which clearly continues to underpin the medium."

Sir Walter Scott called Henry Fielding the “father of the English novel,” and the phrase still indicates Fielding’s place in the history of literature. Though not actually the first English novelist, he was the first to approach the genre with a fully worked-out theory of the novel; and in Joseph Andrews, Tom Jones, and Amelia, which a modern critic has called comic epic, epic comedy, and domestic epic, respectively, he had established the tradition of a realism presented in panoramic surveys of contemporary society that dominated English fiction until the end of the 19th century. ( Walter E. Allen )

He possessed a quick wit, a readier invention, and immense courage. Like many a young man he had hoped for patronage from King George II’s all-powerful minister, Sir Robert Walpole, and failed to get it. He took his revenge in the satires that he turned out so easily in the midst of his pleasures. Henry Fielding was the inventor of the modern English novel. His wit kept its own age on its toes and it gives our a vivid picture of the savage life beneath the elegant veneer of eighteenth-century London.

William Hogarth. A Rake's Progress. " I cannot offer or hope to make a hero of Harry Fielding. Why hide his faults? Why conceal his weaknesses in a cloud of periphrases? Why not show him, like him as he is, not robed in a marble toga, and draped and polished in an heroic attitude, but with inked ruffles, and claret stains on his tarnished laced coat, and on his manly face the marks of good fellowship, of illness, of kindness, of care and wine? Stained as you see him, and worn by care and dissipation, that man retains some of the most precious and splendid human qualities and endowments."

In the late 1720′s a tall, saturnine, hawk-nosed man with a lean,lined face might be seen staggering from the stews of Covent Garden in the early dawn, someties alone, sometimes with a pretty girl of easy virtue on his arm. In that wild quarter of London everyone knew him; his bitter, farcical and savagely satiric plays generated a constant buzz. Money came in easily, a left quickly, for Henry Fielding enjoyed with immense gusto all that London could offer him. Blessed with a wide tolerance for human frailty and drawn by strong appetites to the generous indulgence of his own, Fielding was nevertheless a complex and divided character. …

Familiar with vice , he longed for virtue; an observer of the force and power of evil, he ardently wished that the good might succeed; aware of the brutality and capriciousness of authority, his sympathies always lay with the weak and friendless. Quick in sympathy and warm in response to suffering as he was, nevertheless he possessed another dimension to his character: detachment, an irony, gentle and human maybe, but always in use as he watched himself and his fellow men. And it was this strange mixture of high animal spirits, deeply felt desire to be good, and an acute sense of the ironic that was to make him one of the great novelists of all time, and indeed one of the earliest to achieve such greatness.

Thackeray:He may have low tastes, but not a mean mind; he admires with all his heart good and virtuous men, stoops to no flattery, bears no rancour, disdains all disloyal arts, does his public duty uprightly, is fondly loved by his family, and dies at his work. … 6 As a picture of manners, the novel of Tom Jones is indeed exquisite: as a work of construction, quite a wonder: the by-play of wisdom; the power of observation; the multiplied felicitous turns and thoughts; the varied character of the great Comic Epic; keep the reader in a perpetual admiration and curiosity.

He had more than ordinary opportunities for becoming acquainted with life. His family and education, first—his fortunes and misfortunes afterwards, brought him into the society of every rank and condition of man. He is himself the hero of his books; he is wild Tom Jones, he is wild Captain Booth; less wild, I am glad to think, than his predecessor: at least heartily conscious of demerit, and anxious to amend.

When Fielding first came upon the town in 1727, the recollection of the great wits was still fresh in the coffeehouses and assemblies and the judges there declared that young Harry Fielding had more spirits and wit than Congreve or any of his brilliant successors. His figure was tall and stalwart; his face handsome, manly, and noble-looking; to the very last days of his life he retained a grandeur of air, and although worn down by disease, his aspect and presence imposed respect upon the people round about him.( Thackeray )

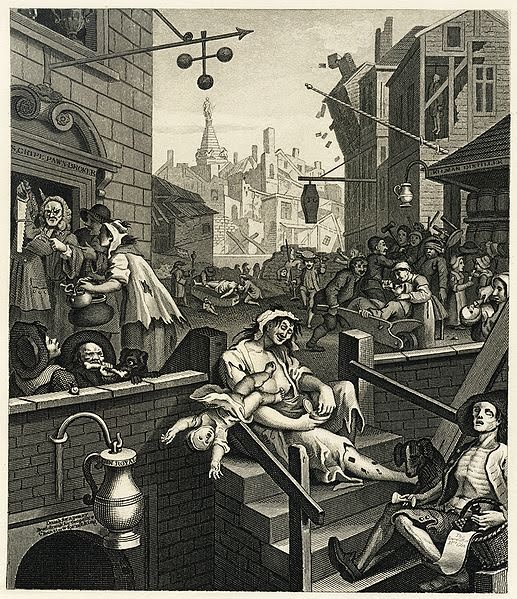

William Hogarth. Gin Lane. 1751. ...”the most sluggish Degree of Public Spirit.” It is surely something more than a coincidence that a few weeks after these warnings were published, Hogarth issued

awful plate of Gin Lane . A third source of crime, in Fielding’s eyes, was the gambling among the ’lower Classes of Life,’–a school ”in which most Highwaymen of great eminence have been bred,” and a habit plainly tending to the ”Ruin of Tradesmen, the Destruction of Youth, and to the Multiplication of every Kind of Fraud and Violence.”--Godden

The most astonishing aspect of the English novel, and the European novel as well, is how young an invention it is, a bare 250 years old. At the time of its birth its very medium, prose, occupied a rather low estate; although the Bible and Henry Chaucer could be seen as a template as a stringing together of anecdotes into a longer narrative. Dafoe had also developed a form of travelogue. For, in spite of the fabulous success of Cervantes’s great epic, “Don Quixote” , few great writers in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries used prose outside of the theatre. The proper vehicle for the highest expression of human feeling remained verse- verse, too, that was hedged about not only by its own elaborate rules of prosody but also strictly limited in its diction: many words of common usage were regarded as alien to good poetry as a botched rhyme or mishandled caesura.

Hogarth. A harlot's progress. Tate:Having insulted and betrayed her wealthy keeper, Moll has been cast out and ‘demoted’ to the position of a common prostitute. As indicated by the tankard in the lower right corner, the dingy garret she now occupies is situated around Covent Garden, which was renowned for its brothels. Moll looks alluringly towards the viewer, unaware of the arrival of Justice Gonson to arrest her. The bottles of medicine around the room suggest that the small black spots on her face are more than just fashionable face patches and are in fact hiding the tell-tale signs of syphilis.

Prose, of course was used for some imaginative literature such as Bunyan’s “Pilgrim’s Progress” , but in general romantic literature did not receive much critical attention. Apart from Bunyan’s work , only a few romances- like the works of Mrs. Aphra Behn, a curious mixture of platitudinous morality, wild adventure, and blatant eroticism have crept into the margins of the history of literature. Within a brief space of fifty years, 1700 to 1750, a dramatic literary revolution took place in England, one that was to influence literature: Through Dafoe, Swift, Richardson and above all, Fielding, prose came to be regarded as a proper vehicle for the expression of the full imaginative treatment of man’s entire moral and emotional life: comedy, satire, tragedy, cold be expressed realistically, by the description of the lives and adventures of men and women whom the readers could recognize as similar to themselves. Classical seventeenth century literature of kings and princes gave way to everyday people doing everyday jobs. The adventures of these people were usually out-of-the-ordinary , but their reactions, their emotional responses, belonged to the recognized world of eighteenth-century, middle-class England.

Tate:Moll Hackabout has arrived at the Bell Inn in Cheapside, fresh from the countryside, seeking employment as a seamstress or domestic servant. She stands, innocent and modestly attired, in front of Mother Needham, the brothel keeper, who is examining her youth and beauty. Needham may be acting on behalf of Colonel Charteris, who stands in the doorway to the right, fondling himself while ogling the new arrival. On the left, the churchman’s horse has upset a stack of pots, portending Moll’s imminent ‘fall’.

The greatest innovator of the new realistic fiction was Daniel Defoe, spy, crook, journalist and tradesman, but still father of the English novel. His quest for realism often led him to use actual records where fact became blended with fiction. He was a great story-teller and wrote flexible prose of a marvelous clarity, but the factual surface of life mattered more to him than emotional response to it. His interest in psychological conflict, reaction to the ambiguities and contradictions of life was non-existant, and his innovations might have easily ended with himself. Swift’s “Gulliver’s Travels” showed how much of Defoe’s technique could be adapted for satire; there was a hunger on the part of the reading public for quasi-realistic fiction that Defoe had uncovered and this was elevated to a more sophisticated diet by Samuel Richardson, a seemingly commonplace little man who made a living as a printer.

Godden:Finally we may turn neither to novelist nor historian, but to the metaphysical philosopher, ”How charming! How wholesome is Fielding!” says Coleridge, ”to take him up after Richardson is like emerging from a sick-room, heated by stoves, into an open lawn on a breezy day in May.” Such are some estimates of the quality of Fielding’s genius, given by men not incompetent to appraise him. … But Fielding’s first novel is not only a revelation of genius. It frankly reveals much of the man behind the pen;…

ADDENDUM:

From Walter Benjamin. “The Storyteller”: The decline of the story is the rise of the novel. Where the story-teller takes his stories from lived experience, either his or that of others, to change it into experience for his listeners; there the novelist is the lonely individual, no longer able to speak exemplarily about his most important concerns, unable to give or receive counsel. In the midst of life’s fullness, and through the representation of this fullness, the novel gives evidence of the profound despair/perplexity (Ratlosigkeit; literally ‘counsellessness’) of the living….

This connection with the practical is a natural one for a story-teller. A story always has its own practical use; the story-teller is someone who has counsel for his listeners. If “having counsel” sounds old-fashioned, this is because the communicability of experience is dwindling. We have no counsel, either for ourselves or for others.

Counsel is less an answer to a question than a proposal concerning the continuation of a story which is just unfolding. To catch up with this counsel one would first have to be able to tell the story. Counsel, woven into the fabric of a lived life, is wisdom.

Story-telling is dying out because wisdom, the epic side of truth, is dying out….

The stories that linger in memory are the ones free of psychological analysis. This process of memorising stories, however, is becoming less and less common, because the situation in which it most easily takes place becomes less and less common: boredom. It is the hearer entranced in the rhythm of labour – such as weaving or spinning – who most naturally assimilates the story. As craftsmanship dies out, so does the story.

The storyteller does not try to convey dry, impersonal information; he sinks the story into his own life, in order to bring it out of him again. Story-telling itself is not a liberal art, but a craft. The great story is therefore a carefully crafted thing, the “precious product of a long chain of causes similar to one another”. It takes time, a lot of time, to create such a story; and this is why story-telling is dying out. “All these products of sustained, sacrificing effort are vanishing, and the time is past in which time did not matter. Modern man no longer works at what cannot be abbreviated.”

If this is so, then there seems to be a connection between the decline of story-telling and the slow vanishing of the concept of eternity from how we conceive our lives. Indeed. The idea of eternity has its source in the idea of death. It is the vanishing of the idea of death that is linked to both the dying-out of story-telling and the dwindling of the communicability of experience.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS