Quoting Hesse’s Steppenwolf -‘Human life is reduced to hell only when two ages two cultures overlap. Now there are times when a whole generation is caught between two ages with a consequence it looses all power to understand itself and has no standards no security no simple acquiescence… such as Nietzsche had to suffer…’

Its nervous, alienated, and often brilliant culture seems unconfortably like our own. But is the sickness that killed the German Republic the same sickness that afflicts America today ?….

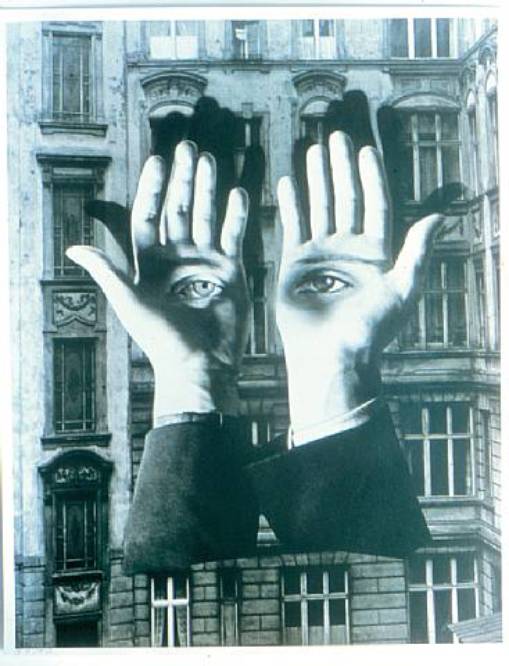

Anarchist demonstrations, anti-globalists, environmental radicals, isolationists,cities in crisis, increasing income discrepancy, political polarization, societal fragmentation,a falling currency, increasing violence, economic meltdowns: this is a partial catalogue, a portrait not of America in the year 2010, but of Germany in the 1920’s. It is easy to take the one for the other. The parallels between Weimar then and America now seem evident, and drawing similar conclusions are tempting. But while the similarities exist, are they real, instructive and applicable? We know America reasonably well; the roots of its malaise, though fascinating have been hashed over to the point of banality. But we do not know Weimar well enough. Before we judge the familiar by the unfamiliar, we should first turn back the curtain on the less well known…..

"Dr. Caligari, a demonic doctor and murderer, untouchable by the arm of the law (through the exploitation and use of a somnambulist), is traced by his antagonist, whom he has robbed of both friend and lover, to a mental hospital where he lives as its director. The vengeful young antagonist uncovers the keeper of madmen as a madman himself; as a madman for whom the example of faded criminal memoirs has become an obsession. And then all these events, reproduced as the youth's story, finally reveal themselves to be the fantasies of an equally sick mind, and therefore a well-disposed audience can make friendly allowances for them, along with the offensive décor; all the more so, since the director - actually a most upright fellow - now also gives the young patient hope for recovery. After all, he has been in the madhouse ..."

In February, 1920, the film “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” had its premiere in Berlin. Germans were hardly in a holiday mood. Less than two years before, they had lost a great war; one which they had been hoodwinked into delusional assurance that it would be won quickly and cheaply to the benefit of all. The defeat had been bitter almost beyond endurance. In addition to losing nearly two million men and suffering another four million wounded- many of whom, hideously mutilated, roamed the streets as pathetic beggars, perfect for george Grosz’s mordant drawings- the country had been subjected to civil war and political assassinations. Even worse, perhaps, it had been compelled to accept the Versailles Treaty. This shameful “dictated peace” left germany truncated and quite literally divided: Versailles drove the corridor of West Prussia, granted to Poland, between East Prussia and the rest of the country; handed Upper Silesia and Posen to the Poles and converted Danzig into a free city; returned Alsace and Lorraine, which the Germans had acquired in the war of 1870, to France;restored Belgian territories in the south; deprived Germany of her colonies; imposed military occupation on the Rhineland; and insisted that the Germans and their allies accept “responsibility” for their “aggression.” The economic losses were enormous and incalculable: the ceded territories contained irreplaceable raw materials and indispensable skilled personnel. Beyond this, there was political isolation and moral humiliation. Thousands of Germans clamored for revision of the treaty and privately hoped for revenge.

"( The Night ) marks Max Beckmann's most impressive appearance on the stage of the artistic avant-garde. This depiction of the brutal murder of a family also stands as a remarkable document of the human condition immediately after World War I. The drastic nature of the image is so overwhelming that the complex structure of the composition - with its acute angles and connecting diagonals - only becomes apparent on closer examination. Beckmann famously called his own style 'transcendental objectivity' - with its echoes of late medieval panel painting and details that reflect his own preoccupation with the formal language of the Cubists."

One could hardly that the statesmen who had proclaimed a republic , chased away the German emperor and minor dynasties, and signed the “intolerable” Versailles Treaty would establish an order that many would respect. In August, 1919, after long and often vehement debate, dominant political groups had indeed written a democratic constitution. But while many supported it passively, few loved it, and many more hated it. The Peace of Versailles and the Weimar Republic fused in people’s minds. Those who wanted to preserve the latter appeared to be apologists for the former; those who longed to destroy the former hoped to destroy the latter at the same time.

The future was uncertain, but this much was clear: the republic had fewer friends than enemies, and it enemies, far more purposeful than its friends, were entrenched and secure. The socialists, democrats and liberal Catholics who created the Weimar Republic had swept away the empire and monarchies; they had even laid hesitant hands on the army- although they had used units of that same army to put down left wing rebellions in Berlin and Munich and elsewhere and had permitted the old bureaucrats and the old judges to remain in their posts.

In Gray Day, 1921, George Grosz savagely epitomized German society."Nationalism, chauvinism, imperialism, industrial materialism and scientific rationalism, driven by capitalism. They were anti-revolution, wanting to preserve the status quo at all costs, so creating a Bland Egalitarian society within the bourgeois with no recognition of the working classes who had done the dirty work of the industrial revolution. The Expressionists saw them as Philistine. As historians put it, ‘the advancement of the industrial revolution had completely outstripped the socio-political advance.’

Nearly all these political survivors were monarchists; many of them were on friendly terms, or in secret alliance, with the paramilitary bands of terrorists that practiced vigilante justice against the Left across the land. Early in 1920, when “The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari” was playing to full houses, it was almost certain that the violence would continue, that the value of the mark wou

rop, and that the allies would go on squeezing as much out of the Germans as they could.The atmosphere of “Dr. Caligari” was as somber as the atmosphere of young Weimar Germany. The film opens with a young man, Francis, sitting with a companion on what appears to be park bench; a lovely young woman, Jane, moves by slowly, as if in a trance. Francis tells his companion that he has been through some strange experiences with the girl. Much of what followes is a record of these experiences. Francis, it appears, is a student in love with Jane. One day, with his friend Alan, he visits a fairground and drops in at the booth of a hypnotist, Dr. Caligari, who exhibits a somnambulist. The sleepwalker, Cesare, an emaciated young man who lives in a coffin shaped box, supposedly can foretell the future.

The aura of terror that pervades the scene is in no way mitigated when we learn that a city official who had snubbed Caligari the night before was found murdered in the morning. Then, when Alan askes Cesare to predict his future, he is told that he has until dawn to live. The prediction proves grimly correct: in the morning Alan is found dead.

Francis seeks to unravel this terrifying mystery; that night he steals into Caligari’s booth and finds Cesare asleep in his box. But he is misled; the sleeping figure is a dummy. Cesare is really off in pursuit of jane, whom he nearly stabs but instead carries away. The police follow the pair across a weird, deserted landscape , until an exhausted Cesare drops the girl and dies. Clearly, he has been in the sinister Dr. Caligari’s power, nothing else; he has committed his crimes under the influence of hypnotism. Exposed, Caligari flees to an insane asylum, but Francis discovers him there and then makes another terrifying discovery: the murderous hynotist and the director of the insane asylum are one and the same.

Dr. Caligari, it seems, had become fascinated with hypnotism and with the story of a vicious eighteenth-century mountebank, and had abused his powers as director of the asylum to experiment with the inmates. He had found Cesare the somnabulist too good a subject to pass up, and so, his fascination degenerated into obsession, he had induced Cesare to commit murders- as a medical experiment. When Francis attempts to wring a confession from Caligari by showing him Cesare’s corpse, the mad doctor loses all control and is put into a straight jacket.

The Pillars of society. 1926. ---George Grosz ...is a german painter, draughtsman and illustrator of the 20's - 30's. He has been influenced by Expressionism and Futurism and most of the prints were photolithographic facsimiles of drawings, was the most outstanding caricaturist and political satirist of the period after World War. In 1933, Grosz emigrated to the United States where he remained until his return to Berlin in 1959. ...

The film does not end there, but cuts back to the opening scene, which now turns out to be a frame for the story. Francis, finished with the telling of his tale, walks into a courtyard filled with outlandish personages . Many of them, including Jane and Cesare, are familiar from the film’s central episode. Obviously francis himself is a madman and has transformed the inmates of the asylum into characters in a fantasy. Indeed, the director soon appears; he is a benign version of Dr. Caligari- a kindly man who has seen through Francis’s delusion and is ready to cure him. It is an improbably cheerful end to a terrifying tale.

ADDENDUM:

By stating ‘Art and nothing but Art! It is the great means of making life possible, the great seduction of life, the great stimulant of life. Art the only counterforce to all will to denial of life, as that which is anti-Christian, anti-Buddhist and anti-nihilist par excellence,’ Nietzsche makes Art the only redeeming factor in an otherwise nihilist godless world.

"In 1920, The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari was instantly recognised as ground breaking and 90 years later it's power hasn't waned. It is the pinnacle of German Expressionism, a visual joy and an enchanting story. It still seeps off the screen and continues to influence our world. Created as a response to the boring and bland cinema of the day, now, as before, this film can be viewed as it was meant to be, still standing strong against empty special effects laden atrocities that insult us around every bend. "

During and after the war many of the Nietzschians felt they needed to reconcile their cultural and individual views with some kind of practical political system, but try as they may to square the circle of Nietzsche’s apolitical, anti-democratic aristocraticism, the nearest application of Nietzschian vital-ism to the collective was either anarchism or communism. The polemics of their intellectual contortions was recorded in detail in Seth Taylor’s Left Wing Nietzschians, The Politics of German Expressionism (published 1990) with articles taken from Herwart Walden’s ‘Der Sturm’ or Franz Pfemfert’s ‘Die Aktion’ and other avant–garde Literary/ Political journals of the time.

The views of the rebelling ‘New Men’ or younger generation Expressionists which included artists, writers, philosophers poets and psychologists, closely mimicked Nietzschian philosophy. This was a middle class revolt, mainly by Left wing intellectuals against what they saw as philistine bourgeois Wilhelmenian liberals responsible for an unadventurous inhibited society. Driven by a spiritual rather than materialistic entelechy they were against everything the liberals stood for – authoritarianism, bureaucraticism, imperialism, nationalism, scientific rationalism or any form of complacency and what they saw as servile conformism. So great were the changes they required that war became an acceptable apocalypse as a means to this end. In literature and art this was translated into a morbid manic-fixation with death, illness, madness, loneliness, desperation, anxiety and alienation. As in Kafka, Werfel, Strindberg, Gottfried-Benn, Alban Berg, Otto Dix, George Grosz. Their main weakness was their elitism; in practical terms they were indecisive, politically ineffective and lacking in unity. ( Peter Rex Valentine )

COMMENTS

COMMENTS