In art sometimes, the more things change, the more nothing is the same. The paper cutouts were Matisse’s final flowering; a last expression of this articulation of traces of solitude and gaiety, what he called “the eternal conflict between drawing and color”. Ever simplifying, ever synthesizing, younger at eighty, than at thirty, he sat in his wheel chair, put aside paint brush for scissors, and filled his last years with patterns of pure color. That Matisse would abandon oil painting and adopt a new technique so late in life surprised many, although it need not have been. Matisse had always been and extremely experimental and unpredictable artist with a deep-seated fear of stagnation….

Zulma. 1950. "Kirk Varnedoe, (Professor of the History of Art, School of Historical Studies, Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton), added his lively insights: "Matisse, at 37, had spent years clawing his way up. He was confronted with a 26 year old with no social graces, who was a `life force' you cannot deny. At first Picasso made him angry, then he went into denial, then he absorbed it and it transformed him. In the 20s and 30s Matisse was alone at the top of the hill. Then World War II came along and neither of them left France, each taking solace from the fact that the other had remained. (Matisse was in the South of France and Picasso remained in Paris). Picasso visited the bed-ridden Matisse, who was busy working on the designs for the Vence Chapel. Picasso had a new young wife, Françoise Gilot, and he hated the clergy and Matisse's preoccupation with religion. Their dialogue continued after Matisse's death in 1954 and Picasso's later sculptures, drawings and folded paper models and cut-outs (papier collé) pay homage to Matisse."---

The Fauve-“wild beast” painters treatred their pigments, according to Andre Derain, one of the group, “like sticks of dynamite, exploding them to produce light.” More prosaically, what Derain, Matisse, Vlaminck, Friesz, Dufy, and Braque, the principal Fauves, wanted was to use color not only to express light but also to construct space.

Matisse, The Piano Lesson (1916-17)"The Piano Lesson depicts the living room of Matisse's home in Issy-les-Moulineaux, with his elder son, Pierre, at the piano, the artist's sculpture Decorative Figure (1908), at bottom left, and, at upper right, his painting Woman on a High Stool. Matisse began with a naturalistic drawing, but he eliminated detail as he worked, scraping down areas and rebuilding them in broad fields of color. The painting evokes a specific moment in time—light suddenly turned on in a darkening interior—by the triangle of shadow on the boy's face and the rhyming green triangle of light falling on the garden. The artist's incising on the window frame and stippling on the left side produce a pitted quality that suggests the eroding effects of light or time, a theme reiterated by the presence of the metronome and burning candle on the piano."

When they spoke of “expressing light” by color, the Fauves meant that they did not want simply to copy light but to render it chromatically. This of course, had been a prime concern of the impressionists in the nineteenth-century, and the Fauves, and especially Matisse, freely acknowledged their indebtedness to impressionist researches in the field of light. Gauguin, who was also deeply indebted to the impressionists, expressed the problem succinctly: “I have observed,” he wrote, ” that the play of light and shadow by no means creates a color the equivalent of light… What, then, could be the equivalent? Pure Color!”

The Fauves were quite ready to follow the impressionists in their use of pure color, but they deplored, as had Cezanne, the lack of form and structure in impressionist painting. Gauguin, in the coarse of making ” the first thoroughgoing organization of impressionist methods” , avoided the impressionist tendency to formlessness but failed, according to Matisse, ” to construct space by means of color, which he uses excessively as an expression of feelings.”

"Iconic Photos Famous, Infamous and Iconic Photos Henri Matisse leave a comment » bressonmatisse Henry Cartier-Bresson’s photograph of Henri Matisse is a symphony of ironies. The great French painter, known for his use of color and called Fauve (wild beast) is depicted in black and white, surrounded by birds and draped by a turban. The photograph does not show energetic, vivid Matisse remembered by many of his contemporaries. Although it is taken in 1944, ten years before the master’s death, Matisse was already a broken man. In 1939, he and his wife of 41 years separated. In 1941, he underwent a colostomy, which confined him to a wheelchair. His daughter is a captive in a Nazi concentration camp. The photograph showed all these ravages."

Because the Fauves, like Cezanne and Gauguin, had rejected the use of a traditional, linear perspective, they relied heavily on the space-building power of color, which depends on the tendency of cold colors-blues and greens- to recede and warm colors-reds, oranges, yellows- to advance.

In practice, the Fauves produced a painting characterized by very shallow depth, heavy bounding lines, thickly rolled impasto, distortion of contour, and explosive color juxtapositions. There was a certain amount of bravado in all this, and in general Matisse remained more orderly and constructive than his colleagues.

His greatest painting of the period- and a landmark in the history of modern art – was that Pagan mural, the “Joy of Life” ( 1906) , which combines Fauve color- yellow ground, pink sky, flame-red trees- with the echoing , curving, fluid forms that would in time become almost a signature in Matisse’s work. The picture was a watershed in Matisse’s career, for in it he abandoned the realistic tradition for the first time since leaving Gustave Moreau’s studio. His fascination with the bacchanalian round of dancing figures in “Joy of Life” was so great that he later made it the central theme of his panel “Dance” , which was commissioned in 1909 by the Russian collector Sergei Shchukin and which is probably Matisse’s best known work.

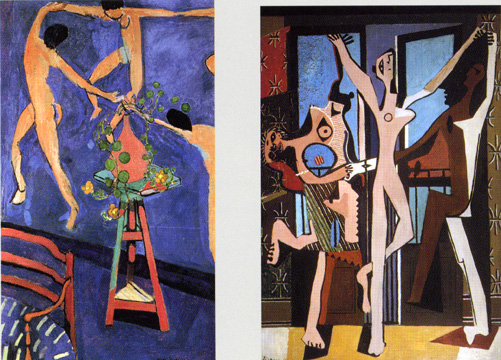

---"Nasturtiums with Dance II," is a meditation on the way art is made from art, in the serenity of the studio, the opposite of Picasso's "The Three Dancers." It is an anti-Cubist work with classical roots," writes Christopher Cook, a dance writer and broadcaster with the BBC and Radio 3 in the September 2002 issue of Tate Magazine. He continues: "The compositional germ of Matisse's " Dance" is the inner scene of "Le Bonheur de Vivre," in which a circle of dancers are having the time of their lives in the distant background. Reworked, that ring draws resonances from a range of classical references the Three Graces and dancers in red ochre on Greek vase - this is a staged neo-classical dance, in its balance and proportion a tribute to Apollo." Picasso's "dance" represents not only the break up of his marriage to Olga Khoklova, who tried to make him "respectable" - he bought tailored English suits in London to please the colonel's daughter - but also a scream of rage at respectability: "In terms of Picasso's development," Mr. Cook continued in his Tate Magazine article, "this picture is a decisive break with the neo-classicism of the immediate preceding years, but maybe it also represents a yearning for the wild and dangerous, for Eros and Thanatos, for the world of horses and bulls and flamenco, for dancing with death with Maenads, not afternoon tea à la Anglaise in

salon with the French windows opening onto the garden. For Dionysius not Apollo"---Read More:

http://www.moma.org/collection/object.php?object_id=78908

http://www.thecityreview.com/matpic.html

ADDENDUM:

Michelle Leight:

The poet Guillaume Appolinaire, who was a close friend of Picasso had this to say about his relationship with Matisse: “If you were to compare Henri Matisse’s work to something it would have to be an orange. Matisse’s work is a fruit bursting with light,” whereas “a painting by Picasso is animated by life and thought and illuminated by internal light. Beyond that life, however, lies an abyss of mysterious darkness.” Picasso preferred to work late into the night, sleeping till noon, completely at home in the surreal world of dreamscapes and altered realities. He did not care too much about his surroundings: they merely facilitated his ability to paint from his prodigious imagination.

Matisse loved the light of Southern France, which infused his life and his work. His living environment was vitally important to him, the eternal aesthete. In documentary photographs luscious flowers adorn his studios, bedroom and living rooms. Fruit lies abundant and ripened to perfection in bowls. Beautifully patterned cloths drape the tables and exquisitely patterned Oriental rugs lay on the floors. Everything is in readiness should Matisse feel the sudden urge to assemble a still life or create an exotic environment for an odalisque. Seeing the women in studio photographs before they are transformed into odalisques show the monumental power of Matisse’s imagination. This was one of the great achievements of the Fauves, the ability to do away with a drab gray dockyard or an unremarkable woman and – with a few masterful licks of pure pigment immortalize them in a radiant world of joy and color.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS