Certainly, the war years seems to bring out some ambiguous behavior on the part of French artists in occupied France. On the one hand, it greatly reduced the competition from foreign sources and citizens not of the “vieux souche” , the pure silken threads of French lineage. It was the Dreyfus affair magnified a thousand fold and the behavior of the ostensibly “neutral” Matisse implied a certain complicity and ambiguity that can appear perplexing; almost a fascination with the aesthetics of fascism and an almost reactionary yearning for “le terreur a la Jacobin”.

Matisse. Henri Cartier Bresson. Cone:Finally, Matisse’s poor state of health has put into question any notion that the artist could have had an indulgent life style and many friends around him during the war years. However, while his age and infirmities might preclude an indulgent sexual life, his fragile state of health did not cause him to be isolated. That is an absurd idea. The artist remained in touch with the outside world through the visits of collectors (Pierre Levy), dealers (Louis Carre, Martin Fabiani), art book publishers (Albert Skira), biographers (Pierre Courthion, Louis Aragon), journalists and artist friends. He even took a trip to Switzerland. Throughout that period, the old Fauve painter Charles Camoin, a longtime friend, is one of Matisse’s most loyal ears and eyes. "I saw your beautiful ensemble, exploding with color, at the Salon

Overall, reading through Matisse’s correspondence with Camoin in La Revue de l’Art (12, 1971) makes me suspect that Matisse’s behavior during Vichy had little to do directly with the presence of Marshall Pétain at the helm of the French government. The master could accommodate himself with “any regime, any religion, so long as each morning, at eight o’clock I can find my light, my model and my easel.” Or so he told Georges Duthuit. (Transition Forty Nine, no. 5, December 1949, p. 115). What was a more likely influence on his behavior was the absence of Picasso from the Paris art scene. For four years, Picasso, the foreigner, did not have a single exhibition of his recent work, and Matisse had the limelight all to himself. During Vichy, the foreigner who had successfully competed with the equally famous French artist (on the latter’s turf, so to speak) was not on view. At a time of French nationalism and Fascism in Franco’s Spain, the Loyalist Picasso and his art, symbols of Judeo-Marxist foreign decadence in France, were in purgatory. ( Michele C. Cone)

Matisse soldiered on. Recovering from an abdominal operation under the care of Lydia Delectorskaya, a blonde Russian woman who had been his model since the early 1930′s , he still produced a remarkable quantity of increasingly abstract oil paintings during the war, together with hundreds of crayon and ink studies, marking a certain “floraison”.

He also began work on four of his most important illustrated books: the collected poems of Henry de Montherlant, of Pierre Ronsard, and of Charles, Duke of Orleans, and the beautiful volume of cutout compositions aptly, if somewhat enigmatically, titled “Jazz”.

Although “Jazz” represents Matisse’s first large scale utilization of paper cutouts, it was prepared for by several earlier experiments. In 1937, at the invitation of the editor E. Teriade, he had made a cutout design for the cover of the first issue of the magazine “Verve” , and he had done other cutouts for the magazine in 1939 and 1943. Even earlier, from 1931 to 1933, he had used pieces of cutout paper while working out preliminary designs for the complex spatial relationships of his Barnes Foundation mural.

"...It was on this visit that Barnes told Matisse that he wanted him to paint a mural for his main hall of the gallery. It was to be forty-seven feet long and eleven feet high and span the three arches above a massive set of windows. Matisse had never done anything so large before but accepted the job in 1931. Barnes sent an enormous canvas to Matisse in Nice and gave him full artistic control over the work. Since Matisse was painting directly onto the canvas unlike most other mural painters, the process involved ladders, trestles and charcoal attached to a bamboo pole for outlines. He also used huge pieces of cut-paper as templates and to try out different colors. This idea later developed into his cut-outs. With The Dance I (1932) finally completed in 1932, Matisse prepared to send the entire canvas to Barnes and learned that the whole mural was too short by about five feet. Rather than adding on an extra five feet Matisse started over with the correct measurements and completed an entirely new mural in April of 1932. It is this second mural, The Dance II, that hangs at the Barnes Foundation..."

“Jazz”, also suggested by Teriade, goes considerably beyond these experiments. Its twenty color plates were reproduced by the stencil process from Matisse’s original cutouts. They treat of circus themes and of poetic abstractions , and are interspersed with philosophic and artistic reflections by matisse in his own, very large handwriting.

Matisse regarded the function of the text , however, as “purely visual.” What mattered to him was the interplay -akin to jazz improvisation- of the acidly intense colors and the audacious and vibrant forms. The shape and movement of objects were rendered with great economy. “One has to study an object for a long time to know what is its symbol,” he had said, and the results of the study are no more stunningly displayed than in “Jazz” which led directly to all the magnificent later cutout compositions.

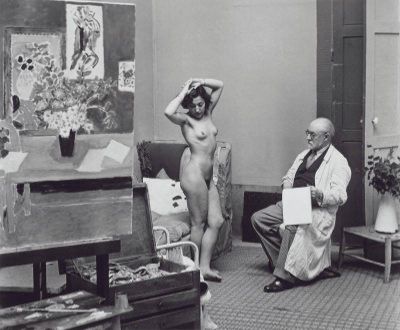

Matisse and his model. 1939. Matisse 1908:Rules have no existence outside of individuals: otherwise a good professor would be as great a genius as Racine. Any one of us is capable of repeating fine maxims, but few can also penetrate their meaning. I am ready to admit that from a study of the works of Raphael or Titian a more complete set of rules can be drawn than from the works of Manet or Renoir, but the rules followed by Manet and Renoir were those which suited their temperaments and I prefer the most minor of the their paintings to all the work of those who are content to imitate the Venus of Urbino or the Madonna of the Goldfinch. These latter are of no value to anyone, for whether we want to or not, we belong to our time and we share in its opinions, its feelings, even its delusions. All artists bear the imprint of their time, but the great artists are those in whom this is most profoundly marked. Our epoch for instance is better represented by Courbet than by Flandrin, by Rodin better than by Frémiet. Whether we like it or no

owever insistently we call ourselves exiles, between our period and ourselves an indissoluble bond is established, and M. Péladan himself cannot escape it. The aestheticians of the future may perhaps use his books as evidence if they get it in their heads to prove that no one of our time understood anything about the art of Leonardo da Vinci."

“All his life Matisse was a connoisseur of woman’s body, and she was sometimes — conspicuously — the phallic woman, as I have argued elsewhere. It was Matisse’s mother that lifted his spirit and liberated his creativity during a youthful sickness — it seemed implicitly mental, however physical it also was — by giving him a box of colors during his long convalescence. He used this gift of art to explore Mother Nature’s body, devoting his life to it, in search of the mystery of its creativity — the mother’s and nature’s generative power, which he experienced as healing — and its even more mysterious self-sufficiency. It had to be because her body was simultaneously feminine and masculine, passive and active, receptive and productive –consummately whole — that she was so creative, spontaneously, vigorously, yet without apparent effort, which is the way Matisse wanted his art to seem.” (Kuspit)

ADDENDUM:

It is hard to know what to make of Matisse’s remark upon hearing the news of Vlaminck’s arrest as a collaborator after the Liberation of Paris in August 1944. In a letter to Charles Camoin on November 16, 1944, he says, “Basically, I think that one should not torment those who have diverging ideas from one’s own, but that is what today is called la Liberté.” On the one hand, Matisse’s tolerance of diverging ideas in art was magnanimous, but his lack of political commitment meant one less voice on the side of “la Liberté” during Vichy, and an important one at that. The fact that Vlaminck had been on the side of those who caused Amélie and Marguerite great harm during the Occupation years escapes the great master’s consciousness. Yet had there been fewer individuals sharing Vlaminck’s ideas, and more of them on the side of Amélie and Marguerite,( daughter and wife tortured by the Gestapo) human lives would have been saved.

Read More:

http://blogs.princeton.edu/wri152-3/jholt/archives/001911.html

http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/books/cone/cone12-19-05.asp

COMMENTS

COMMENTS