Prim and proper? Hardly. But, it was jolly old England. Refreshingly, they were not politically correct. The PC Nazi/Yuppie was in an idyllic, and mythological future. It really began with William Hogarth. Hogarth was the first of these new artists who pierced through the heavy armor of British austerity.In this sense Hogarth’s London,was a tentative beginning still rooted in puritanical past, that with the likes of John Locke was beginning to smell a waft of liberalism. Still, it was a country and a London of the mind, that repressed the senses, and its heavy intellectual overkill postponed the possibility directly pleasurable experiences or their genial celebration. It was allegory and posture but nothing remote to the erogenous zones or carnality. He might study graffiti or signboards “with delight”, as he said, but chiefly because that study offered that “pleasing labour of the mind to unfold mystery allegory and riddles”.( Uglow ) Kind of boring, but after Cromwell, witch burning , public execution and rampant child abuse…

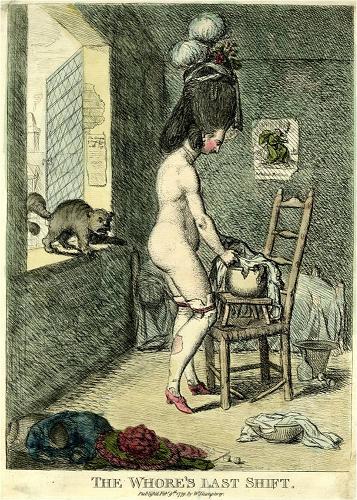

---In her garret, the naked whore concludes her night’s business by washing her last shift in her chamberpot (the pun on ‘shift’), the incongruous finery of her hairpiece belied by her tattered stockings, both indicating that she had come down in the world. Hogarthian symbols: the cat arches its back in lust and the pot is cracked. The print might intend no more than a conventional if eroticised comment on the contrast between the outward presentation of the self and the corrupted inner reality, echoing Swift’s satire to that effect, Beautiful young nymph going to bed. But is it contemptuous of the poor woman, or does it seek to disclose the poignancy of her plight? The answer –- as never in Hogarth –- is left to the viewer. --- Read More:http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/march2008/gatrell.html

With Hogarth there is a certain lack of warmth and generosity. But, it was a beginning. Hogarth’s street scenes and spatial conventions are later kidnapped and parodied by the ensuing generations.The new artists added a fluidity and informality, and, the introduction of caricature displaced a pseudo-realism which blunted the invasive darkness and imposed a moral ambiguity. It was a new species of artist and painting which could be termed the moral comic. Meaning, thereby, that the instinctive humor of the man’s art is generally ,not, always directed to some moral purpose, some lesson of conduct to be thence derived. Where the moral lesson is either absent or less intrusive—the man’s fancy runs absolutely riot in humorous observation.By the time of Victoria, and Jane Austen putting pen to paper, manners had been domesticated and humor tamed, as an increasingly influential middle class defined itself in opposition to both the laboring classes and the aristocracy. It was Dickens famous “purity of the middle-class” in search of an identity. The Mister Darcy’s were no longer doing cow imitations,belching contests or dandling prostitutes on their knees.

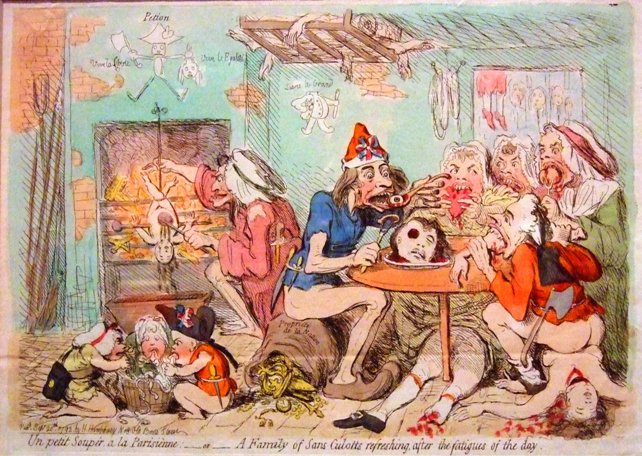

---After James Gillray’s initial positive reaction to the fall of the French aristocracy, he changed his view regarding the Revolution and “his first attacks on radical sympathizers with the Revolution date from as early as December 1790” (Bindman 33). James Gillray’s print of the September massacre in 1792 shows a plebeian Parisian family, who feast on the limbs and organs of their victims. The term ‘sans-culottes’ usually referred to the long trousers worn by artisans and shopkeepers, in contrast to the knickers (culottes) more commonly worn by the aristocracy and wealthy bourgeoisie. A striking aspect in this painting is that all the male characters are literally portrayed without their pants (sans culottes), engaged in various acts of sexual or physical violation. This represents the Revolution as an act of rape. Read More:http://scripties.let.eldoc.ub.rug.nl/FILES/root/Master/DoorstroomMasters/EngelseTaalenCultuur/2008/RepresentingMarie-An/Ma-1268643-Henstra.D..pdf

We are not talking here of an aesthetic beauty of form and nobility modeled on the Italian tradition, but rather the humor of life even in its most sordid tragedies.Thus pleasure and consumption were integral components of Georgian politics and social life. It was a world where pleasure and consumption mixed freely with politics and commerce. For politicians,it was not sufficient to win over the populace with political rhetoric. Voters and influential citizens could expect to receive alcohol and female attention.

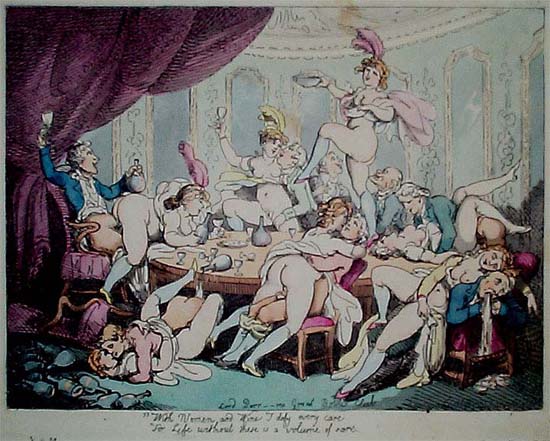

---“No other city was so dynamic, free and uncensored, and nowhere else were the comedies of snobbery and emulation played out and ridiculed so determinedly,” he writes. The excesses of the rich, the corruption of the political elite and the absurdities of fashion provided rich material for comic artists, who, thanks to virtually nonexistent libel laws, could fire away at will. Nothing was sacred, and no one was safe, least of all the royal family.---Read More:http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/29/books/29book.html?_r=1&ref=books&oref=slogin image:http://www.sexualfables.com/Orgies-English-style.php

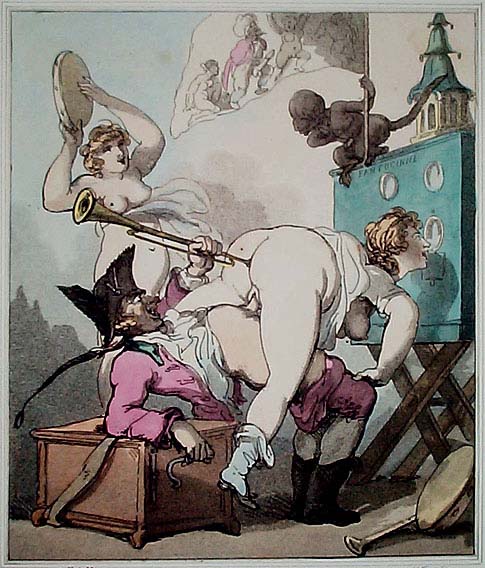

The humor on display in the prints of James Gillray, Thomas Rowlandson, and George Cruikshank , three of the better known artists, was often coarse, bawdy, scatological and obscene. Private parts were on graphic display. Chamber pots and their contents stood front and center. Prostitutes cavorted with princes. Everything that the readers of Jane Austen regarded as private or shameful was shown in living color, on large, beautifully printed sheets hung in the windows of dealers for all London to see, and to laugh at.

---The first of Hogarth's satirical moralising series of engravings that took the upper echelons of society as its subject was 'Marriage A-la-Mode'. The paintings were models from which the engravings would be made. The engravings reverse the compositions. In this, the second in the series of paintings, the marriage of the Viscount and the merchant's daughter is quickly proving a disaster. The tired wife, who appears to have given a card party the previous evening, is at breakfast in the couple's expensive house which is now in disorder. The Viscount returns exhausted from a night spent away from home, probably at a brothel: the dog sniffs a lady's cap in his pocket. Their steward, carrying bills and a receipt, leaves the room to the left, his hand raised in despair at the disorder. The decoration of the room again comments on the action. The picture over the mantlepiece shows Cupid among ruins. In front of it is a bust with a broken nose, symbolising impotence.--- Read More:http://www.nationalgallery.org.uk/paintings/william-hogarth-marriage-a-la-mode-2-the-tete-a-tete

The pen of Swift and the graver of Hogarth in the early eighteenth century found in England conditions not very dissimilar to those which awaited Philipon and Honoré Daumier in Paris of the early nineteenth century—that is, a public which had come through a period of intensely active political existence to a complete and complex self-consciousness, and which enjoyed (just as in Paris La Caricature, when suppressed, found a speedy successor in Le Charivari) sufficient political freedom to render criticism a possibility. And from Hogarth through Sandby and Sayer and Woodward to Henry William Bunbury, and onwards to that giant of political satire, James Gillray, and his vigorous contemporary Thomas Rowlandson, what a feast of material is spread before us; what an insight we may gain, not only into costume, manners, social life, but into the detailed political development of a fertile and fascinating period of history….

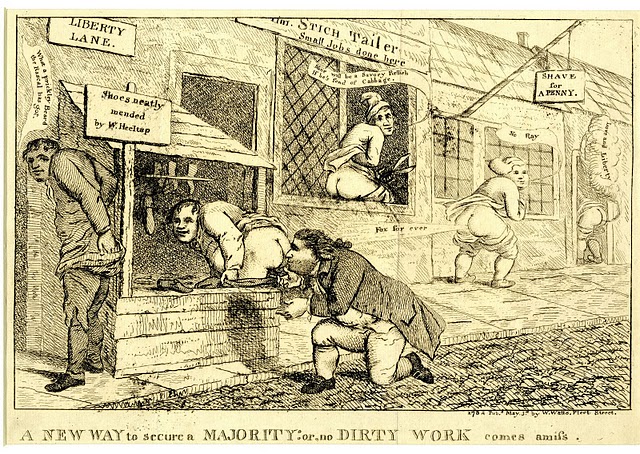

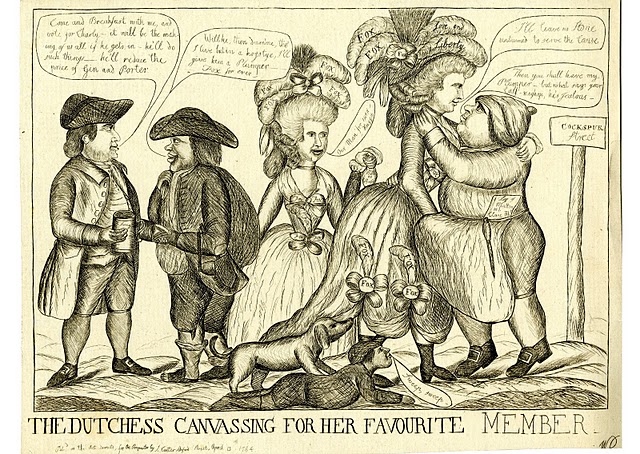

William Wells. 1784. ---Firstly, in 1784 they were called prints, not cartoons. Secondly, the prints were not as ephemeral as modern cartoons; they were expensive, carefully crafted designs, sold on individual sheets of canvass in print-shops. Accordingly, the prints’ consumers, until at least the 1790s, were to be found mainly in the highest ranks of society and the content of the majority of the prints was political. Even Queen Charlotte used to enjoy perusing prints with her breakfast, until she was shocked by those of the 1784 election. Thirdly, prints often displayed a nationalistic bias. Lastly, and the most importantly in regards to this essay, is that prints were far more likely to satirise the politician on a much deeper level than their physical appearance or policies. From the 1780s the rising influence of nationalism and caricature in these prints ensured that designs were ‘crueller, more freely expressive and aggressively personalised’ than they had ever been before. Read More:http://unruly18thcentury.blogspot.com/

…In the earlier age Hogarth is ready to present the very London of his time in the levée and drawing-room, in the vice and extravagance of the rich, in the industrious and thriving citizen, and those lowest haunts where crime hoped to lurk undisturbed. In the century’s close Gillray’s pencil notes every change of the political kaleidoscope. In his prints we seem almost to hear the muffled roar of the Parisian mob, clamorous for more blood in those days of Terror; or we watch the giant forms of Pitt and Buonaparte fronting each other as the strife comes nearer home to Britain. Read More:http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29647/29647-h/29647-h.htm

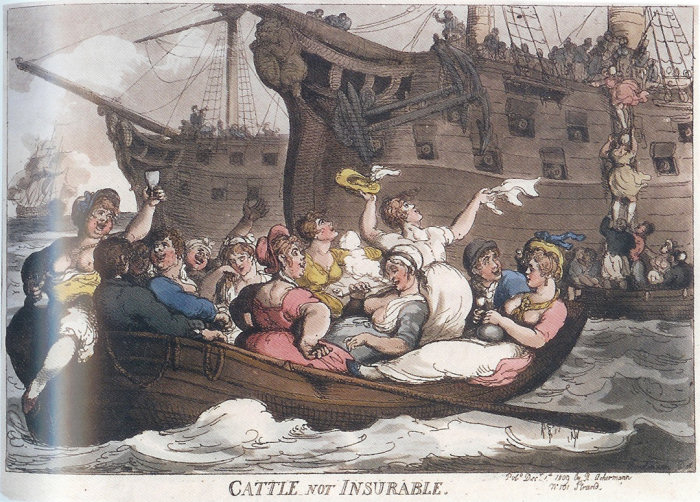

But Life contains—thanks be—not only coarse, distorted types of humanity, exaggerations of foolish fashion, and political antagonisms, but grace and beauty, even with the changing form of the time-spirit; and it is just here that Rowlandson infinitely surpasses those contemporaries …His female figures have often that rich English beauty which we find in Reynolds, Hoppner, or sometimes in Morland; and his landscape has qualities of very exceptional merit….

---Mr. Gatrell is more interested in the other half, the prints that dealt with gossip, fashion, manners and sexual relations, although the two halves often overlap, especially in the many prints devoted to the sexual escapades of the prince regent, the future George IV. Taken as a whole these social prints depict a society in which the well-born mingled easily with the lower orders, whose speech and behavior they freely adopted, a society that tended to laugh at rather than condemn drunkenness, lechery and the idle pursuit of what the early-19th-century novelist Pierce Egan called “fun, frolic, fashion and flash.” Mr. Gatrell pays close attention to the subgenre known as debauchery prints, which usually depicted young clubmen and prominent political figures at table or tearing up the town. Copious vomiting, urination, erotic play and bad behavior of every sort figured prominently in these prints, but such scenes were offered as comic spectacles rather than moral lessons. Prostitution tended to be depicted in a manner that was “comically upbeat rather than judgmental.” Women were assumed to be just as hungry for sex as their male pursuers.--- Read More:http://www.nytimes.com/2006/12/29/books/29book.html?_r=1&ref=books&oref=slogin image:http://www.sexualfables.com/Orgies-English-style.php

He might, we are frequently tempted to think, have been a painter worthy to take a front rank even in that magnificent English eighteenth-century school, which included Reynolds, Gainsborough, Romney, Hoppner, among its glories; but as we come to study his life we shall find in the insouciance of his character, in the very facility of his genius, the causes which made him—not, indeed, entirely to our loss—only the greatest caricaturist of his time. Read More:http://www.gutenberg.org/files/29647/29647-h/29647-h.htm

William Dent. 1784. ---Littered throughout these propagandist prints (historical research suggests that while kisses were exchanged for votes by female Foxites, Georgiana herself did not take part) are allusions to promiscuity influencing the election. So the prints, in line with those against the use of drink and money in canvassing, do not attack women for being involved in politics – but instead imply that female influence is being used excessively by the Foxites, in particular by the duchess of Devonshire. The prints do not stop at depicting the body politic being corrupted by bribes from the Foxites; in true late-eighteenth-century fashion the characters of Fox and Cavendish are shown to be corrupted by their own manners of consumption. Read More:http://unruly18thcentury.blogspot.com/

ADDENDUM:

But what stands out in the 1784 Westminster election are the number of prints which denigrate these two figures for partaking in electioneering activities which were actually commonplace in Georgian Britain: plying potential candidates with drink and money. The duchess and her female friends, likewise, were derided for their role in the man’s world of politics, although in reality women regularly partook in electioneering. In addition to these attacks on canvassing methods, satirists attacked the personal vices of Fox and Georgiana: Fox for his love of gambling and the duchess for her presumed sexual promiscuity. The prints ridicule and revile the politicians for their personal excessive consumption as well as for treating voters excessively. At a period where moderation was all-important in politics, the prints contend that the Foxites neglect this principle…. Read More:http://unruly18thcentury.blogspot.com/

Hogarth. The Enraged Musician. ---One of the hallmarks of a classic work of art is that it retains its relevance down the years. I very often think of this print while attempting to play the piano in my noisy household.--- Read More:http://tpsaye.wordpress.com/2008/11/19/

Nevertheless, influencing voters by satisfying their carnal desires remained an integral component of politics in the eighteenth century, as Charles Churchill affirmed:

We form our judgement in another way;

And those will best succeed, who best can pay:

Those who would gain the votes of British tribes,

Must add to force of Merit, force of Bribes. Read More:http://unruly18thcentury.blogspot.com/

Read More:http://theartistsprogress.blogspot.com/

---It shows a wonderful boatload of whores being ferried to service the sailors on the ships berthed at Portsmouth, and in this print the girls stand for a part of male life’s rich feast, and, hopefully, for the girls’ own exuberant happiness also. We are nowadays conditioned to assume that eighteenth-century prostitutes were exploited and miserable. But the tone of the satires obliges us to ask whether the girls themselves would have thought of themselves in this way, in an era when life expectations were modest and the stigma attached to prostitution weaker than they became. Rowlandson and other artists have no hesitation in suggesting that countless whores might actually have been happy. --- Read More:http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/march2008/gatrell.html image:http://joyfulmolly.wordpress.com/2007/06/12/resourcebook-my-what-a-big-p-ipe-you-have-horatio-naval-naughtiness-in-the-18th-century/

——————————————————————————–

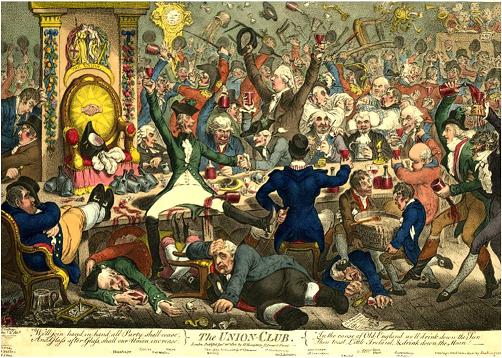

Gillray. The Union Club. ---We could read this as a satire on the Whig grandees and the Prince of Wales. But I think the print is too amused by its own excess to be read simply as a satire. Gillray seems half in love with what he mocks. The print may chastise the prince and the whigs for their indulgence, but it doesn’t invite us into full-blown disgust, as Hogarth’s debauchery prints were meant to. Here again the print unavoidably comic.--- Read More:http://www.literarylondon.org/london-journal/march2008/gatrell.html

COMMENTS

COMMENTS