During the 20th century many different art forms and movements came to life. The Dutch painter, Piet Mondrian (1872-1944) was a pioneer in the development of abstraction one of the most important art movement of the times. His works from the early 20th century brought with them a new wave of thought and a surge towards the development of Modern Art as we know it.

The perception of relationships between the parts was at the heart of revolutionary artistic experience in the twentieth century.Piet Mondrian asserted that “Beauty consists of relationships. Art has shown that the question is how these relationships are created. Form only exist in terms of creating relationships so that form creates relationships and relationships create form, like instruments that merge with that which can’t be described, but only created. These relationships are similar, both destructive and constructive and in dynamic balance. There is intelligence not only associated with the brain, not at all cognitive, but it feels and thinks.”

Mondrian called his style "neoplasticism," which also means "new form" in Dutch. The style was based, he explained, "on an absolute harmony of straight lines and pure colors underlying the visible world." Mondrian believed that the rhythms of urban life – were the reoccurring theme for the neoplastic genera. He embraced urban life spending time in Paris (1919-1938), London (1938-1940) and New York (1940-1944), searching each metropolis for clues that would lead him towards the harmony he rejoiced through his paintings. "I felt that only the Cubists had discovered the right path."

Indeed, the neurobiologist Zeki holds the view that “. . . artists are neurologists, studying the brain with techniques that are unique to them and reaching interesting but unspecified conclusions about the organisation of the brain” . ( Piet ) Mondrian expressed a similar view that the ultimate goal of abstract art is the expression of pure reality: “Despite cultural lags and breaks, there exists a continuous progression in the disclosure of true reality by means of the abstraction of reality’s appearance”

Piet Mondrian, a founding member of the De Stijl movement, was a Dutch modern artist who used grids, perpendicular lines, and the three primary colors in what he deemed “Neoplastic” painting. Mondrian and the term “vision perception” is inextricably linked. Visual perception is ambiguous and visual arts play with these ambiguities. While perceptual ambiguities are resolved with prior constraints, artistic ambiguities are resolved by conventions. Is there a relationship between priors and conventions? While most conventions seem to have their roots in perceptual constraints, those conventions that differ from priors may help us appreciate how visual arts differ from everyday perception.

"Broadway Boogie-Woogie, 1942 - 43 At the start of the Second World War, Piet Mondrian left Paris for London and later New York. Here he began a new form of painting which was a complex lattice of interlacing red, blue and yellow lines. ‘Broadway Boogie-Woogie’ is one such abstract geometric painting that seems to be inspired by the cheery music of the time. Piet Mondrian died of pneumonia in New York City in 1944. Mondrian’s ‘Neoplastic’ style continues to be used in the advertising, design, graphics, fashion and art fields today. "

“When ( David ) Hubel and ( Torsten ) Wiesel were still in diapers, Dutch artist Piet Mondrian was painting works in an attempt to show, as he put it, that every visual form is ultimately reducible to “the plurality of straight lines in rectangular opposition.” Hoping to reveal the “constant truths regarding forms,” Mondrian turned his paintings into minimalist arrangements of rectangles and primary colors. As Zeki, author of Splendors and Miseries of the Brain, notes, the geometrical art of painters like Mondrian and Kazimir Malevich is remarkably similar to the geometry of lines sensed by the visual cortex—as if these painters broke apart the brain and saw how seeing itself occurs.

Composition in Red, Yellow and Blue. 1921. "Indeed it seems that these artists argued about their intuitions on these matters to the finest degree. Mondrian took exception to Theo Van Doesburg using diagonal lines and wrote to him: ‘Following the high-handed manner in which you have used the diagonal, all further collaboration between us has become impossible’."

Mondrian wasn’t consciously trying to imitate the receptive fields of our brain cells. He was just trying to create a visually arresting image. But it was precisely that aesthetic impulse, that desire to captivate the eye, that led Mondrian to create such neurologically “accurate” art. In other words, the strange beauty of a Mondrian is rooted in the strange habits of visual neurons, obsessed as they are with straight lines. Abstract art seems so bizarre—so unrepresentative of anything at all—but it takes advantage of the innate properties of the brain. The geometric brushstrokes are a nod to the quirks of our visual neurons, which prefer straight lines.

Mondrian was unalterably diffident, forever dissatisfied with the stage he had reached; but at the end he was also wholly certain that he had found his personal signature. That is why, in his rare autobiographical moments, he would stress his creative solitude at the expense of the comforting companionship he had previo

known and valued. As he himself put it, “I had to seek the true way alone”.

"While Picasso and Munch looked at reality and reported their depressed observations, others retreated from the world and proceeded to strip away from art anything that they could. On the grounds that other media such as photography and literature reproduced reality and told stories, many eliminated as much content as they could from their works. Art came to be a self-contained study of dimension, color, and composition. But the reductionist, stripping-away game led quickly to challenges even to those features. In the sterile color studies of Piet Mondrian and Barnett Newman, any sense of a third dimension disappeared. In Kasimir Malevich's near-monochrome White on White, color differentiation was abandoned. And with Jackson Pollock's erratic paint drips and splatters, any role of artistic composition was eliminated."

It is to easy to dismiss such a claim as myth-making. It was, but Mondrian’s private myth, like many such myths, contains a good measure of truth: a great artist’s style is always bound to contain a powerful infusion of individual talent. Yet, even for the loneliest of artists, private history can never be complete history. The other dimensions of his life have their psychological aspect and leave a psychological deposit. However much the artist himself may undervalue them, however deeply he represses them, what psychologists call the “significant others” are always there, and they are always significant.

It was only natural that the leap into abstraction should have been a collective enterprise. In the early days of cubism there were times when the painters themselves found it hard to tell a Braque from a Picasso; in the founding months of neoplasticism, a painting by Theo van Doesburg, a co-founder of “De Stijl” , was interchangeable with one by Mondrian. These painters were pioneers crossing the frontier in a select caravan.

They tossed aside all the benefits of recognizable iconography and instead presented an art demanding to be experienced, and judged, by reference to itself alone. With this demand, abstract art revolutionized man’s aesthetic perception, more dramatically, perhaps, than the triumphant discovery of perspective in the early Renaissance….

“A Mondrian does not consist of blue rectangles and red rectangles and yellow rectangles and white rectangles. It is conceived – as is abundantly clear from the unfinished canvases – in terms of lines – lines that can move with the force of a thunderclap or the delicacy of a cat. “Mondrian wanted the infinite, and shape is finite. A straight line is infinitely extendable, and the open-ended space between two parallel straight lines is infinitely extendable. A Mondrian abstract is the most compact imaginable pictorial harmony, the most self-sufficient of painted surfaces (besides being as intimate as a Dutch interior). At the same time it stretches far beyond its borders so that it seems a fragment of a larger cosmos or so that, getting a kind of feedback from the space which it rules beyond its boundaries, it acquires a second, illusory, scale by which the distances between points on the canvas seem measurable in miles.

” ‘The positive and the negative are the causes of all action … The positive and the negative break up oneness, they are the cause of all unhappiness. The union of the positive and the negative is happiness.’ The palpable oneness of the solitary flower or tower, being subject to time and change, had to give way to the subliminal oneness of a vivid equilibrium.”

Composition with Gray and Light Brown 1918; Oil on canvas, 80.2 x 49.9 cm; Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, Texas

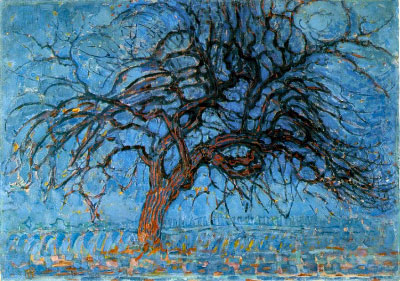

…Mondrian was the most reluctant of revolutionaries. The deliberate, hesitant pace of his artistic career is a measure of the difficulty and the daring of the move to abstraction. It was not until 1911, when he was nearly forty, that Mondrian went to Paris and was, he recalled, “immediately drawn to the cubists, especially to Picasso and Leger.” But “gradually” he adds, “I became aware that cubism did not accept the logical consequences of its own discoveries; it was not devloping abstraction toward its ultimate goal, the expression of pure reality.” In 1912 Mondrian undertook his first really drastic deformations of nature; his early experiments, paintings of trees or sand dunes, dating only a year or two before, retain sufficient verisimilitude to permit easy identification of their subject matter.

It was not until 1915 that his paintings of the ocean lost all but the remotest connection with nature. And it was not until 1917, when he was forty-five, that he took the last step and began to compose canvases consisting entirely of rectangles. The grids that won immortality for him are the work of an even older man. They date from 1920. …

Piet Mondrian New York City 1941-42 Oil on canvas 119 x 114 cm (46 7/8 x 44 7/8 in) Musee national d'art moderne, Centre Georges Pompidou, Paris Piet Mondrian (March 7, 1872 – February 1, 1944) was a Dutch painter and an important contributor to the De Stijl art movement, which was founded by Theo van Doesburg. Despite being well-known, often-parodied, and even trivialized, Mondrian's paintings exhibit a complexity that belie their apparent simplicity.

Might there not be ways, in which artists are “tuned in” to the deep structures of the universe? Might it not be in this area that we find universal values in art? It is difficult, of course, to disassociate them from culturally learned responses. But there are instances when aspects of art feel “right” that might point us in this direction.

As an example, take the work of Piet Mondrian. He began as a painter of realism, but moved from that to what we most associate him with, his well-known paintings of grids and squares with bright blocks of primary colours. Mondrian was a theosophist, and much influenced by eastern spirituality. In his paintings, he openly sought what he referred to as ‘the deep order of the universe’. Responses to Mondrian’s paintings have been tested by a psychologist who took the paintings and slightly changed the patterns of verticals and horizontals. Viewers were then exposed to both the original and the newer versions in the form of a blind test. A majority of people in his experiment showed significant preference for the originals. There is, it appears, a ‘felt rightness’ about these. But we should be careful. Perhaps this is a learnt cultural preference. Have we, in Sian Ede’s words, grown to like “mondrian-ness’?

" It reminds me of my studies with Sas Colby on line and simplicity. Sheer genious. I like it when an artist finds a link between my work and someone I admire. Piet Mondrian. I like that. I would have never connected us in a million years. Just call me a good ole "Mondrian Cowgirl." (What's Dutch for "Happy Trails?")"

… Had Mondrian stopped painting in 1911, before he went to Paris, he would have secured an approving, if modest, paragraph in the history of modern art as a gifted painter of landscapes and flowers. His art would have been enjoyed for its subtle color and its refined draftsmanship, and for a certain confidence of attack. But Mondrian’s place would have remained modest because his canvases, however pleasing, were derivative. Like most other painters, Mondrian for many years painted like other painters.

Hubel & Wiesel inserted microscopic electrodes into the visual cortex of experimental animals to read the activity of single cells in the visual cortex while presenting various stimuli to the animal’s eyes. They found a topographical mapping in the cortex, i.e. that nearby cells in the cortex represented nearby regions in the visual field, i.e. that the visual cortex represents a spatial map of the visual field.

Individual cells in the cortex, they found, responded not to the presence of light, but rather to the presence of edges in their region of the visual field. Furthermore, cells were found which would fire only in the presence of a vertical edge at a particular location in the visual field, while other nearby cells responded to edges of other orientations in that same region of the visual field. These orientation-sensitive cells were called “simple cells”, and were found all over the visual cortex.

This suggested that simple cells posessed a patterned receptive field, with excitatory and inhibitory regions (represented by white and gray regions below) so that the cell would fire only if it received input (due to light) in the excitatory portion of its receptive field in the absence of input from the inhibitory portion. In other words the cell responds to spatial features which correspond to the spatial pattern of excitatory and inhibitory synapses in its own receptive field.

This operation is analogous to the operation of “edge detectors” in image processing, which process an image by spatial convolution with an edge “kernel” consisting of adjacent positive and negative values.

In addition to simple cells, Hubel & Wiesel also discovered “complex cells” which also responded to edges of a specific orientation at a specific location in the visual field, but unlike the simple cells, these cells would respond in a contrast-insensitive manner, i.e. the same cell might respond to a dark/light edge and a light/dark edge but only if it were at the proper orientation. Furthermore, the complex cells would respond to their edges in a larger region of the visual field. This suggested that complex cells received input from lower level simple cells by way of a receptive field.

Even higher level “hypercomplex” cells were discovered which would respond to more complex combinations of the simple features, for example to two edges at right angles to each other in a yet larger region of the visual field.

All of this suggested a hierarchy of feature detectors in the visual cortex, with higher level features responding to patterns of activation in lower level cells, and propagating activation upwards to still higher level cells. This model of a hierarchy of feature detectors performing successive processing of the visual input remains the dominant view of visual processing in the visual cortex. It has inspired a number of computational models of visual processing involving successive stages of image convolution using patterned spatial kernels.

COMMENTS

COMMENTS