Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947) was not a revolutionary artist but he synthesized several different styles to create works of striking painterliness and memorably glorious color. He borrowed a lightness from the Impressionists, a bold palette from the Post-Impressionists and Fauves, a compressed dimensionality from Matisse and added an immense intensity of his own. His oeuvre combines the poignancy of Degas with the lyricism and luminosity of Rothko. He may not be in the very top tier of artists and, indeed, much of his oeuvre, is a bit disappointing – too sketchy, too unresolved, almost sloppy. Nevertheless, at his best he is marvelous…( Carter B. Horseley)

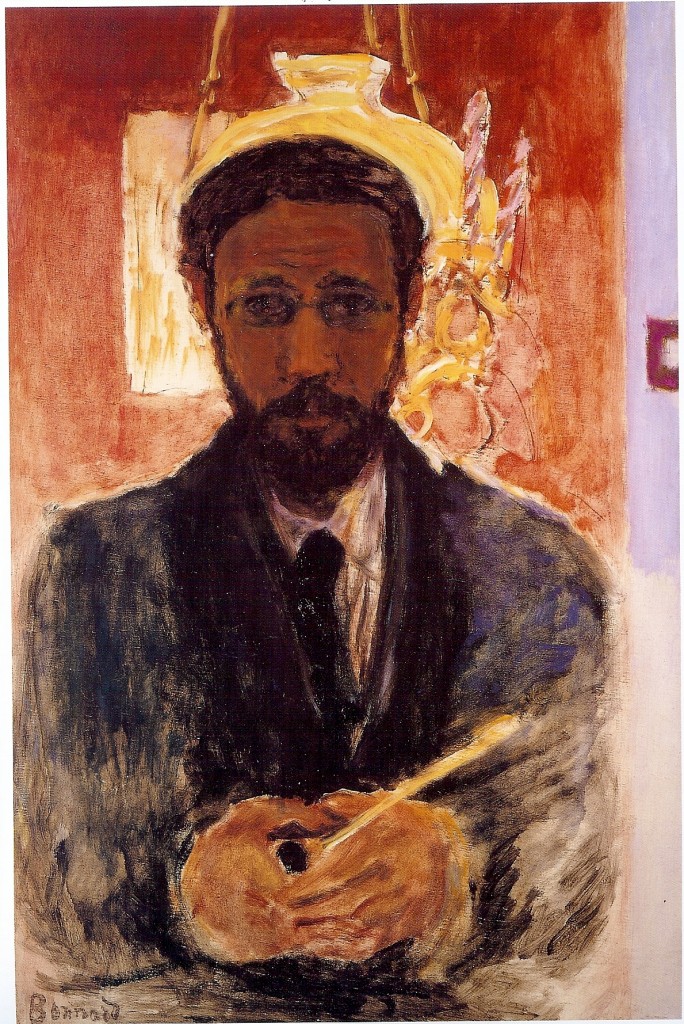

Tony Thomas:The Self Portrait with Lamp shows him as an introverted and myopic man of 40, his features masked in the shadow of a lamp. The worried expression and tentative grip on the paintbrush perhaps expessing his fears that he was being eclipsed by the brilliance of his contemporaries, although Picasso and Matisse had yet to make their mark with the public: Luxe, Calme, et Volupté had appeared in 1905 and Les Demoiselles d’Avignon in 1907. However, in 1902 Bonnard had collaborated with Ambrose Vollard on an edition of Daphnis et Chloé by Longus with 156 lithographic illustrations by Bonnard. In 1906 Gertrude Stein had acquired the nude painting of Marthe called Siesta. A couple of years later he had travelled throughout Europe, to England, Tunisia and Algeria and so was by no means as reclusive and naive as the portrait might suggest.

He saw her, a girl of twenty, in a Montmartre street one day in 1895, and at once with the sudden boldness of shy people, spoke to her. She was to be his companion till her death in 1942. She told him her name was Marthe de Meligny, hinting at aristocratic origins, although she was more prosaically known as Maria Boursin and was simply a midinette. He believed her story, or pretended to, and did not find out her real name until 1925, when he married her, a gesture which meant so little to him that he had not even bothered to notify his family and asked his concierges to act as witness.

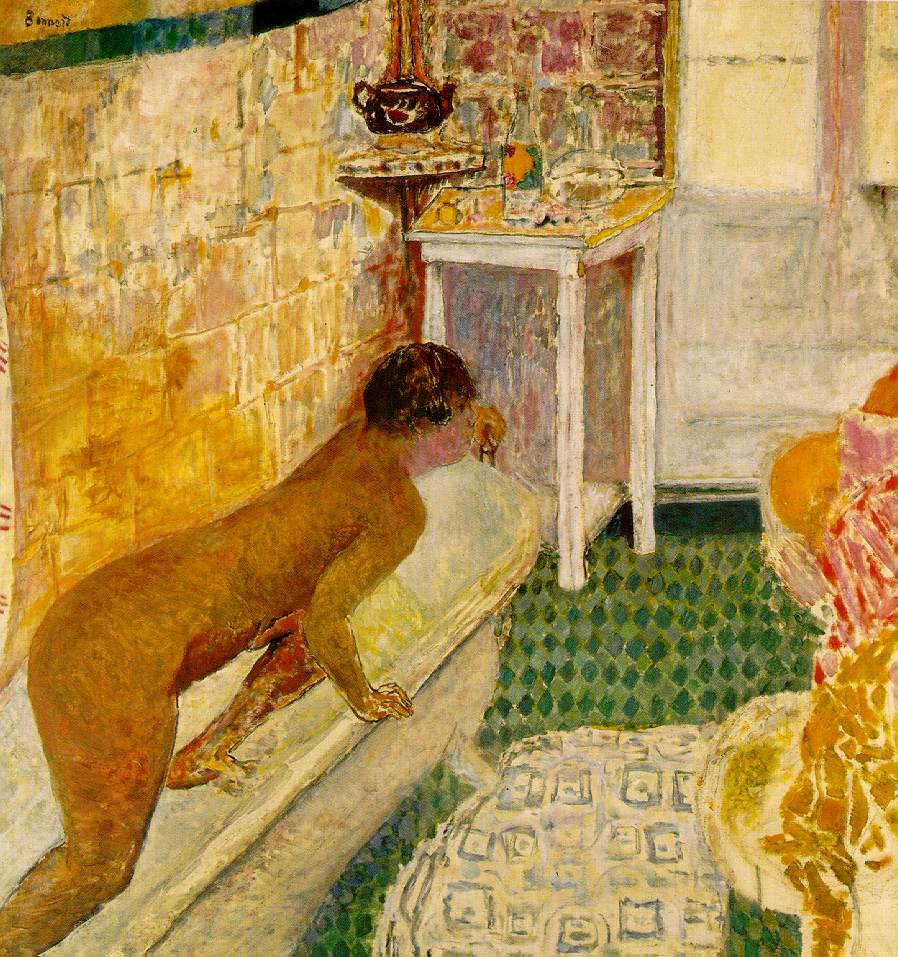

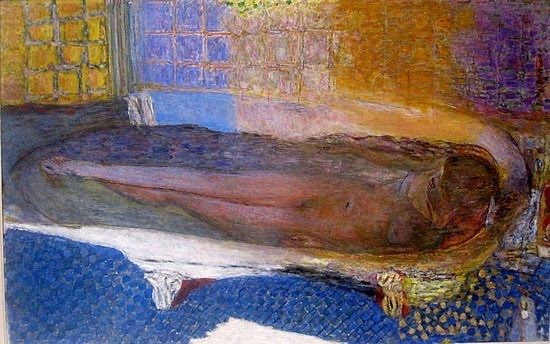

Marthe, on the other hand, meant a great deal to him. She was to be the model for a long series of exquisite nudes, the quintessence of youthful lovliness. What is remarkable about them is their combination of sensuousness and chastity. Degas’s Toulouse-Lautrec’s and even Renoir’s nudes somehow betray the intrusion of a man’s eye; those of Bonnard comb their hair, dry their backs, or put on their stockings with the easy abandon of people unobserved.

Thomas:The term Intimiste in the title is well defined by the painting Indolence. How different from Manet’s Olympia or from Cezanne’s crude imitation of that painting. There is no hint of self-consciousness with Bonnard’s “private view” of his sprawling mistress or justification of a gentleman’s formal relationship with prostitutes and lower class women, so well depicted by Degas and Toulouse Lautrec. Already the figure is subordinated to the design of the painting, with its diagonal division between purplish brown shadow and the golden glow of sunlight from the window. Here is the essence of bourgeois paradise, “When lovely woman stoops to folly,” and the beginning of Bonnard’s method of creating a hinterland between reality as seen by the eye and the visual Eden he wished to create out of his personal life.

She was of fragile health; hence after the turn of the century the couple tended more and more to desert Paris for the country; eventually, they moved to La Cannet, a village above Cannes. And now, for the first time, Bonnard turned seriously to landscape painting, which was finally to occupy him almost to the exclusion of all other themes. Marthe liked the country for another reason. She was pathologically shy and jealous: away from the city she could have Pierre to herself. Here, he would not run off to see his friends on the pretext of taking the dog for a walk. Thus she gradually isolated him from society.

No doubt Bonnard sometimes found the weight of her tyranny heavy to bear. Yet he loved her as he loved no one else. He slept in an old iron bed in a monastic cell, but he himself made the furniture for her room. “His” paintings lay rolled on the floor, “hers”- she painted occasionally under the name Marthe Solange- were framed and hung on the walls. When she died, Bonnard informed no one of the event, but he locked her room as it was and never allowed a visitor to enter it.

Picasso was very critical of Bonnard, perhaps because he ignored the Spaniard’s revolutionary transformation of painting. “That’s not painting,” Picasso said. “Painting can’t be done that way. Painting isn’t a question of sensibility; it’s a matter of seizing the power, taking over from nature, not expecting her to supply you with information and good advice.”

…I am not sure whether the term “vocation” exactly applies to me. What attracted me then was less art itself than the artist’s life, with all that I thought in terms of free expression, of imagination and liberty to live as one pleased . . . I wanted at all costs, to escape from a monotonous existence. –Pierre Bonnard “I dream of seeking the absolute,” Pierre Bonnard wrote to Henri Matisse early in November 1940…. Bonnard, in fact, frequently distorts his perspectives to achieve an awry ambiance. Many of his compositions seem somewhat askew….

In fact she had provided him with what he needed most: independence and uninvolvement. Unlike more strongly armored, if not stronger personalities, Bonnard could not have withstood the pressure of modern life. He was acquainted with it, enjoyed, but as an observer, a “flaneur” . He would have loved the world, had the world consented to leave him alone. It is this fear of involvement, this determination to travel light, that explains the extreme sobriety and simplicity of his ways.

Bonnard. Getting Out of the Bath. 1926. Graham Nickson:For Bonnard drawing was sensation, and taking possession of the image. The next step was the translation of these notations into color, not local color, but the color that came from his interior logic. The s

tion and its perceptual basis change mysteriously into the concept or the idea of color.Although his paintings had been bringing considerable prices since the 1920’s, he lived and worked in conditions of near poverty, and often of acute discomfort. During the Second World War, when a friend, after having seem him writhe unhappily in his hard, bamboo rest chair, brought him a mattress to make it softer, he firmly refused it: “Not that. I am not going to get accustomed to comfort at my age. Comfort means the end of liberty.”

For the same reason, he refused the chains of riches. He kept his money in an old shoe box, and it was not until he was well over seventy that he opened a bank account. Glory was as cumbersome as wealth-hence his boundless modesty. Someone reported to him that Picasso had made deprecating remarks about his work; his reply was to pin a Picasso on his wall- a reproduction, since the only original work of an artist in his possession was a small Renoir nude inscribed to him.

He had turned down the Legion D’Honneur in 1912, probably to protest the fact Cezanne had been denied it; when during the last war, he was again entreated to accept the honor, he answered, “When I was forty-five, I caused my mother the greatest sorrow in her life by refusing: Why should I accept now that I am seventy-six and alone?”

…”I’m especially drawn to trying to understand the defining aspects of early modernism, and what happens to narrative subject matter is certainly one of them. Between 1906 and 1912, between Matisse’s Bonjeur de vivre (1905-06) and the invention of collage, there’s an amazing change. In these six years, the idea of a painting as a depiction of narrative finally gives way to a kind of painting where the narrative aspect is effectively passed over to the beholder. The beholder is asked to ‘perform’ the picture perceptually, and thereby combine the parts to provide the unity (or lack of it) that narrative subject matter did previously. This certainly happens in Bonnard’s paintings….I think that what he took from Matisse and Picasso was the idea of painting by accretion – by parts added to parts – and it began to click for him that this had a relationship to both his early interest in ambiguities and his Impressionist interest in shifting natural perceptions. He was able to bring it all together in paintings that change as you look at them, where the subject-matter therefore emerges in the time of the viewing, and where the beholder, therefore, is actively engaged in the production of meaning.”…

Bonnard. Dining Room on the Garden .1933.Cornelia Lauf, Guggenheim:Bonnard resolutely painted subjects such as Dining Room on the Garden for most of his life, being called an intimiste and très japonard for his attempts to create a charged psychological moment in a virtually non-perspectival domestic space. This painting, one of more than 60 dining-room scenes he made between 1927 and 1947, is neither decorative (as these works have often been called) nor is its subject truly his first concern. Dining Room on the Garden sets out to capture the moment and the intrinsically ungraspable play of mood and light. On close inspection, the colored areas within the flattened picture plane lose their relation to the objects depicted: a chair melds into the window frame; the window echoes the painting’s borders, becoming a view within a view; and Marthe, the painter’s oft-depicted wife, merges passively into her surroundings. It is in his ability to create a timeless microcosm while laying bare the gesture of applying paint to canvas that Bonnard’s Modernism is revealed.

Even as a man of eighty, he still had a boyish charm. This phenomenal preservation is even truer for his work, so fresh and clear that it excludes even the thought of a wrinkle, of a shadow, and of the effort that went into its making. Yet its childlike spontaneity is actually the result of painstaking labor. Bonnard’s genius is ingenuousness recaptured by ingenuity. He took a great deal of time to complete most of his paintings, and he never really considered them finished.

The Terrace at Vernonnet. 1939.--- It is probably Bonnard’s last view of the terrace at his house in the Seine. He purchased the property in 1912 and used it as a subject for his painting until 1939. Elements of his comfortable bourgeois life are in evidence: fruit, wine, company. The gaze of the central figure is rather enigmatic, as is the gesture of the woman at the right. The main figures concentrate on their inner world rather than on their companions or the tasks in which they are engaged. Bonnard painted a shaded corner of the irregularly shaped, raised terrace that surrounded the house. Only a banister indicates the steps that descended to the sprawling garden below. In the painting the terrace serves as a stage, with the garden rising like a curtain beyond. Toward the end of his life Bonnard approached abstraction, increasingly subordinating the subject in order to obtain the desired effects of colour and light.---Gandalf

ADDENDUM:

( Tony Thomas):The immediate implication of Picasso’s remark is that not only should the artist dominate nature but should reject it where necessary, an attitude which led to the increasing abstraction and invention of the inter-war years, leaving the likes of Bonnard, and perhaps Matisse, behind to complete the programme started by impressionism as transformed by the post-impressionists Gauguin and Van Gogh. One can argue that building on the work of Cézanne, as Picasso and Braque did with cubism, does not exclude the intense development of colour and design derived from the works of Gauguin and Van Gogh carried through by Matisse, Bonnard and others….

His subject matter became focussed on domestic interiors, augmented by garden scenes and extended to full scale landscapes, all of which he mastered and developed using his intense repertoire of complex colour. In this regard, he is comparable to Matisse and Chagall, although without the latter’s peculiar symbolic bestiary. During the 1920s the convergence between the works of Matisse and Bonnard are striking, although the latter differed in retaining the expression of volume in still life and figurative painting, in contrast to Matisse’s relative abandonment of modelled forms in favour of flat, lithographic areas of colour. Both, however, used decorative design elements as previously described, which in Matisse’s case were influenced by Islamic rather than Japanese art….

COMMENTS

COMMENTS