The avant-garde revolution was over. Ironically, their work also signified the end of avant-gardism and the onset of post-modernism. The avant-garde had become history. Its contradictions, the emptiness, the triumph of form over substance, essentially its transformation into rote kitsch meant it would keel over and die under its own weight. After the originality of the initial impulse, the Clement Greenberg attack of Nazi kitsch art, the post-modernists arrived, intuitively, that these opposites were part of the same system. Their achievement was to reconcile seemingly irreconcilable styles.

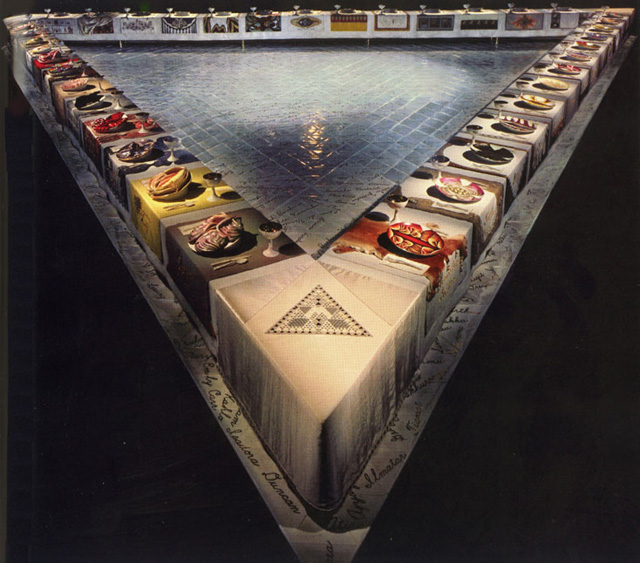

--The principal component of The Dinner Party is a massive ceremonial banquet arranged in the shape of an open triangle—a symbol of equality—measuring forty-eight feet on each side with a total of thirty-nine place settings. The "guests of honor" commemorated on the table are designated by means of intricately embroidered runners, each executed in a historically specific manner. Upon these are placed, for each setting, a gold ceramic chalice and utensils, a napkin with an embroidered edge, and a fourteen-inch china-painted plate with a central motif based on butterfly and vulvar forms. Each place setting is rendered in a style appropriate to the individual woman being honored.--- Read More:http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/dinner_party/place_settings/

It was not conceptually original, a breakthrough, but it amply demonstrated a unity of opposites shown to be part of a larger esthetic whole. This meant converting high-art into kitsch cliches. Emotionally defective ones through suggesting the banality of its form stripping them of art and significance. It was a bit of a punk esthetic that brought out a psych-social use of abstract art to be more significant and meaningful than the self-importance and narcissism of formal purity which bizarrely recalled the same false and empty values of the Fascist esthetic it ostensibly was opposed to. It did not aim to achieve a Kandinsky quality of the spiritual in art, but rather, and importantly, asserted that adversarial and critical content trumped the mainly bullshit of vague, ill-defined, esoteric inner logic.

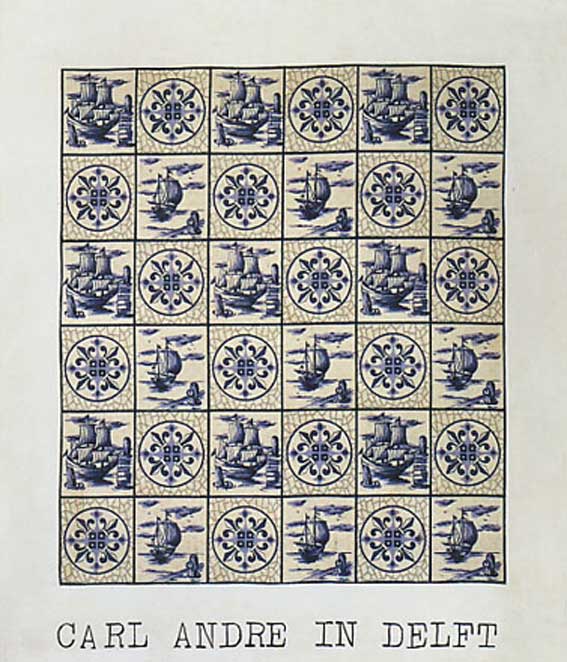

Kuspit: There are two works that seem to me telling of the 1970s: Sigmar Polke’s sardonic Carl Andre in Delft, ca. 1968 — an important year for the counterrevolution against sociopolitical orthodoxy, as the May riots in Paris, the riots provoked by the Chicago Seven, and the Vietnam protests in the United States indicate — and Judy Chicago’s feminist The Dinner Party (1974-79). However different, both rebel against the tyranny of Minimalism, the purest — and emptiest — abstract art ever made. For Chicago it was a symbol of masculine as well as esthetic authoritarianism….

---One on the most pointed, early deconstructions of minimalism is Sigmar Polke’s Carl Andre in Delft, 1968, (above left). In this work Polke symbolically contaminated the transcendental purity of Andre’s grid with “mere” decoration. In so doing he reminded us of the pioneering modernist architect Adolf Loos’ famous connection between “ornament and crime”. In his eponymous 1908 essay (Wikipedia) Loos argued that because criminals were enamoured with tattoos there was a clear link between ornament crime. For Loos such observations provided clear proof that the elimination of ornament from modern architecture was both ethically and aesthetically superior. In retrospect his argument is outstanding because of its absurdity.--- Read More:http://artintelligence.net/review/?p=288

…For Polke it was a symbol of America’s absolutist rule of modern art. For both the American female artist and the German male artist Minimalism was the inexpressive dead end of art. Both vehemently attacked it, Polke using irony, Chicago using ideology, to assert a new individuality — woman’s individuality and independence in Chicago’s case, German individuality and independence in Polke’s case. Thus the oppressed rose up against the art and social establishment. They questioned and demystified — indeed, discredited and debunked — the official system of dominance and exclusivity. What had hitherto been uncritically accepted as esthetically and culturally superior was unceremoniously relegated to irrelevance. A supposedly major art was shown to be minor, and the vanquished Germans no longer humbly emulated the victorious Americans. It was a truly great moment in modern art and social history. Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit7-28-06.asp…

---The first name of each woman begins with an illuminated letter magnificently incorporating a small symbol or motif that references the subject’s importance. The table itself is set upon the enormous Heritage Floor comprised of over two thousand hand-cast, gilded and lustered tiles, inscribed with the names of 999 other women of importance. The Dinner Party dominated art headlines during its early history and, though enormously popular with the more than a million viewers who saw it in a dozen cities worldwide, it bore the brunt of hostile opposition from some quarters of the art world who saw it as an assault on modernist traditions and from the political right who felt threatened by its feminist agenda. Perhaps emblematic of how much things have changed, today it is thought of as, in the words of renowned critic Arthur C. Danto, “one of the major artistic monuments of the second half of the 20th century.” It has influenced the lives and work of thousands of people and has become the iconic example of how art can change the world, the expanded role for the artist in society and women’s freedom of expression. Read More:http://www.brooklynmuseum.org/eascfa/feminist_art_base/gallery/judy_chicago.php?i=1288

…The avant-garde lost credibility and value because it failed in its ultimate mission of esthetic transcendence. It was unable, despite its best efforts, to insulate the individual from history, sparing him the annihilative emotional effects of barbarism by affording esthetic salvation. But avant-garde art left a legacy of esthetic innovation that seemed valuable in its own right. Its ideas and forms could be used for “impure,” commonplace — and communal — purposes….

…Polke comically transforms Andre’s Minimalist grid of metal plates into painted Dutch tiles, undermining their seriousness. Chicago’s huge triangular table has place settings for 39 “great ladies,” to refer to the title of the series of paintings of queens that preceded The Dinner Party. Interestingly, Chicago’s work, a collaborative effort with craftswomen, also uses tiles: there are 144 on the floor — the same number that Andre used in his early floor pieces, each a 12 by 12 foot square made of 12 by 12 inch squares (a regular version of Malevich’s irregularly placed square within a square, indicating that Suprematism had become standardized) — in the center of the triangle. But there is a crucial difference: both Andre’s metal plates and Polke’s painted tiles are square, while Chicago’s tiles are equilateral triangles, echoing the shape of the table. For Chicago the triangle is a symbol of the vagina, and it is vaginas — each monumental, assertive, projecting and vividly colored — that we see on each dinner plate. Instead of phallic power, we have vaginal power — or rather phallic vaginas, that is, the mythical vagina of all-powerful, goddess-like woman….

---Polke continues his attack on abstract art in such works as Moderne Kunst, a spoof on gestural painting, and Konstructivistisch, a mock geometrical painting (both 1968). They seem to parallel Roy Lichtenstein's '60s series of brushstroke paintings, which also cut Abstract Expressionism down to ironical size.--- Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit7-28-06.asp

…These vaginas symbolize the creative achievement, against all social odds, of the women they belonged to, among them the African-American abolitionist-feminist Sojourner Truth and Emily Dickinson, the reclusive poet, as well as Georgia O’Keeffe (she was still alive when the work was made), whose flower forms have been interpreted

vaginal displays. They may have been an inspiration if not direct model for Chicago’s more dynamic — indeed, vigorously Abstract Expressionist and sculptural — vaginas. …Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit7-28-06.asp

ADDENDUM:

The new German art not only broke the taboo against irrational, perverse imagery — imagery that resonated with unconscious meaning (“pandemonium,” as Georg Baselitz called it) — but against sociohistorical consciousness in art. American pure art had declared both irrelevant to the true, higher purpose of art. In their different ways, Baselitz and Anselm Kiefer, among others, use modernist methods to convey the depressing effect of the disaster Germany brought upon itself in the Second World War. Both are what might be called culturally narcissistic artists. They hold an artistic mirror up to the unconscious of their society, faithfully mirroring its self-destructiveness. They show its wounded body and broken spirit, reminding postwar Germany of what it would rather forget. They picture the ruins of German greatness, suggesting that it was never more than a myth. They are refreshingly if morbidly emotional in a society reluctant to acknowledge the suffering it has caused. They are the first truly tragic artists who appeared in any country after the Second World War.Read More:http://www.artnet.com/magazineus/features/kuspit/kuspit7-28-06.asp

COMMENTS

COMMENTS